The American Civil War

Part 7: Out West

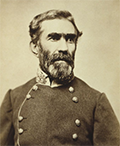

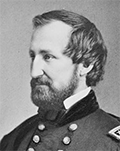

In the summer of 1863, Union Maj. Gen. William S. Rosencrans (right) and the Army of the Cumberland were advancing on Chattanooga, considered to be the "Gateway to the Deep South." The Union troops had left Murfreesboro, Tenn., and were marching toward Chattanooga. On the northeastern outskirts of Chattanooga, along the Tennessee River, were elements of the Army of Tennessee commanded by Braxton Bragg (left). Rosencrans didn't do exactly as advertised, having conducted a series of misdirections to hide the real path of his army, which was streaming along to the southwest of the city, more toward Georgia. Bragg made the tactical decision to leave Chattanooga and engage the Union army. The city of Chickamauga was in Georgia, 12 miles southwest of Chattanooga. The two armies clashed near there, beginning on September 18. The timely arrival of Lt. Gen. James Longstreet and reinforcements strengthened Bragg's hand, and the commanding general drew up a plan to drive the Union troops from the field. That is what happened on the third day of fighting. Rosencrans ordered a full-scale retreat back to Chattanooga. Bragg took the initiative and ordered his men to follow the retreating Union troops to Chattanooga. Once there, the Confederate troops seized the high ground. Among that high ground was the very high indeed Missionary Ridge. Grant, the overall commander in the West, organized new lines of supply for Chattanooga. Along with those new supplies came 40,000 troops, led by Joseph Hooker and William T. Sherman.

On November 24, Hooker led a three-division-strong contingent of men in an attack on 2,400-foot-high Lookout Mountain. The Confederate defenders had all the advantages of the high ground, but they did not at all have superior numbers. Their guns could fire only so often, and they had only so much ammunition. As well, a thick fog rolled in during the afternoon, blunting the counterattack ordered by Confederate Brig. Gen. John C. Moore. Hooker and his men eventually reached the top of the mountain and dispatched all of its defenders. Thus ended the so-called "Battle above the Clouds." Meanwhile, Gen. William T. Sherman was leading an attack on Missionary Ridge, or so he thought. Sherman's men actually seized another bit of high ground, Billy Goat Hill, and then met with enough resistance from the men of Maj. Gen. Patrick Cleburne at Tunnel Hill that they called off the rest of the attack. The following day, November 25, Thomas's men stormed a number of rifle pits that the Confederate defenders had dug on Missionary Ridge. The Army of the Cumberland halted to get organized but came under withering fire from elsewhere on the ridge. Thomas, without specific orders to do so, urged his men onward. They succeeded in taking control of the ridge and putting the Army of Tennessee to flight. A few months after the Battle of Gettysburg, a Pennsylvania lawyer, David Wills, began a drive for a national cemetery. The result was the Soldiers' National Cemetery, which was dedicated with great fanfare on Nov. 19, 1863.

Wills secured the great orator Edward Everett, who counted stints as Governor of Massachusetts, a member of the House of the Representatives and of the Senate, and Secretary of State (under President Millard Fillmore) among his accomplishments, to give the major dedication address. Almost as an afterthought, Wills invited President Abraham Lincoln. The dedication ceremony was one of great fanfare, with a military band and procession and a crowd estimated at about 20,000. The cemetery was full of soldiers who had died on the battlefield at Gettysburg. These "honored dead" were buried in ground next to the old town cemetery. All around were the violent results of the battle. Nearby was a sign that read: "All persons found using firearms on these grounds will be prosecuted with the utmost rigor of the law." Everett spoke for about two hours. Lincoln spoke for two minutes. But it is Lincoln's speech that, despite his assertion that "the world will little note, nor long remember what we say here," is remembered, often quoted, meticulously analyzed, and revered. In early 1864, Sherman and a large Union force went through Mississippi, destroying crops and roads and railroads and other parts of the Southern infrastructure. Sherman then ended up in Vicksburg as the overall commander in the West, replacing Grant, who had been called by Lincoln to be General-in-chief. During this time, with the exception of Confederate Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest, Union armies scored the vast majority of victories in battles through the West and the Deep South, including Florida. In May, Sherman, at the head of a very large force, began a campaign of devastation the goal of which is Atlanta. Next page > The Road to Petersburg > Page 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White