The Alien and Sedition Acts

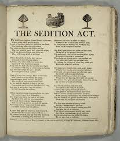

The most incendiary of the four laws, to Democratic-Republicans and, indeed, to many modern scholars, was the Sedition Act. According to the text of the Act: SECTION 1. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America, in Congress assembled, That if any persons shall unlawfully combine or conspire together, with intent to oppose any measure or measures of the government of the United States, which are or shall be directed by proper authority, or to impede the operation of any law of the United States, or to intimidate or prevent any person holding a place or office in or under the government of the United States, from undertaking, performing or executing his trust or duty, and if any person or persons, with intent as aforesaid, shall counsel, advise or attempt to procure any insurrection, riot, unlawful assembly, or combination, whether such conspiracy, threatening, counsel, advice, or attempt shall have the proposed effect or not, he or they shall be deemed guilty of a high misdemeanor, and on conviction, before any court of the United States having jurisdiction thereof, shall be punished by a fine not exceeding five thousand dollars, and by imprisonment during a term not less than six months nor exceeding five years; and further, at the discretion of the court may be holden to find sureties for his good behaviour in such sum, and for such time, as the said court may direct. On the face of it, the Sedition Act would seem to violate the First Amendment guarantees of freedom of speech, freedom of the press, and freedom of assembly. The Federalists, who had a narrow majority in Congress, argued that the politically charged rhetoric uttered by their political opponents, both in speech and in print, was anti-democratic because it was critical of the governing party of the day. Both political parties were used to speaking and writing things highly critical of their opponents; then, morseo than now, newspapers espoused highly charged and politically slanted ideas and opinions. Organs of both political parties had done this for years, but the Federalists were now defining charges against them as charges against the government itself. The words of the Sedition Act specifically did not include the Vice-president, who at the time was Jefferson, a leader of the Democratic-Republican Party. The Sedition Act gave the federal government the power to fine or imprison those judged to be guilty of sedition, and government officials did indeed fine and/or imprison a number of publishers of Democratic-Republican-leaning newspapers. Adams signed the Sedition Act into law on July 14, 1798. In October of that year, Matthew Lyon, a Republican representative from Vermont, was the first prosecuted under the Sedition Act. Lyon had written a letter highly critical of President Adams, saying that he had a "continued grasp for power," and had spoken out against the President in publicm forums. Lyon defended himself at trial, arguing that he was expressing his political opinion, not inciting a revolt. A jury convicted him of having "bad intent" and sentenced him to four months in jail and a $1,000 fine; he also had to pay court costs. While Lyon was in jail, he won re-election. His home state and his political party judged him a hero. A Federalist effort to expel him from Congress because of his conviction failed. Others prosecuted under the Sedition Act included:

More than two dozen people were fined and/or sentenced under the Sedition Act, including one man who was fined $150 for insulting the President. Like the Alien Acts, the Sedition Act had an expiration date: Section 4 designated that as March 3, 1801. The Sedition Act did indeed expire on that day and was not renewed. It had proved to be very unpopular with the public at large, who had not re-elected Adams as President. Rather, Jefferson was the new President and the beneficiary of a Congress the majority of which belonged to his political party. Jefferson pardoned all those serving sentences handed down under the Sedition Act. Congress paid their fines. Of the four acts, only the Alien Enemies Act did not have an expiration date. It is technically still a law. Congress in 1918 amended the act to make it applicable to women as well as to men. First page > Background and the Alien Acts > Page 1, 2 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

SECTION 2. And be it farther enacted, That if any person shall write, print, utter or publish, or shall cause or procure to be written, printed, uttered or published, or shall knowingly and willingly assist or aid in writing, printing, uttering or publishing any false, scandalous and malicious writing or writings against the government of the United States, or either house of the Congress of the United States, or the President of the United States, with intent to defame the said government, or either house of the said Congress, or the said President, or to bring them, or either of them, into contempt or disrepute; or to excite against them, or either or any of them, the hatred of the good people of the United States, or to stir up sedition within the United States, or to excite any unlawful combinations therein, for opposing or resisting any law of the United States, or any act of the President of the United States, done in pursuance of any such law, or of the powers in him vested by the constitution of the United States, or to resist, oppose, or defeat any such law or act, or to aid, encourage or abet any hostile designs of any foreign nation against United States, their people or government, then such person, being thereof convicted before any court of the United States having jurisdiction thereof, shall be punished by a fine not exceeding two thousand dollars, and by imprisonment not exceeding two years.

SECTION 2. And be it farther enacted, That if any person shall write, print, utter or publish, or shall cause or procure to be written, printed, uttered or published, or shall knowingly and willingly assist or aid in writing, printing, uttering or publishing any false, scandalous and malicious writing or writings against the government of the United States, or either house of the Congress of the United States, or the President of the United States, with intent to defame the said government, or either house of the said Congress, or the said President, or to bring them, or either of them, into contempt or disrepute; or to excite against them, or either or any of them, the hatred of the good people of the United States, or to stir up sedition within the United States, or to excite any unlawful combinations therein, for opposing or resisting any law of the United States, or any act of the President of the United States, done in pursuance of any such law, or of the powers in him vested by the constitution of the United States, or to resist, oppose, or defeat any such law or act, or to aid, encourage or abet any hostile designs of any foreign nation against United States, their people or government, then such person, being thereof convicted before any court of the United States having jurisdiction thereof, shall be punished by a fine not exceeding two thousand dollars, and by imprisonment not exceeding two years.