Tenochtitlan: Aztec Capital

Tenochtitlan was the capital of the Aztec Empire for nearly two centuries, from 1325 to 1521. The product of sophisticated engineering and determined city-building, it was at its height one of the highest-populated cities in the world. The victim of a conqueror's rage, it is no more.

The Aztecs arrived in what became their most well-known homeland, what many today call Mesoamerica, in the early 13th Century, taking over from the Toltecs (and, some sources say, having a hand in their downfall). Some sources say that the homeland of the Aztecs was Aztlan, to the north, and that the people took their name from their homeland, from which they migrated (some sources say during a considerable period of time) after a great drought. Some sources name them the Mexica and say that they referred to themselves in that way. Other sources name the Aztecs the Tenochca, the origin for the eventual Aztec capital, Tenochtitlan.

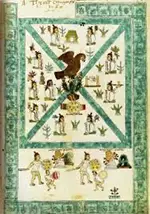

The foundation story for the people and their capital is shrouded in legend and mystery. According to the story related most often, an ancient prophecy said that the migratory people would know when it was time to settle when they came to a location at which they saw, perched atop a cactus, an eagle with a snake in its beak. The Aztec/Mexica people saw just a sight in 1325, on a small swampy island in Lake Texcoco. Soon afterward, they got to work building their capital.

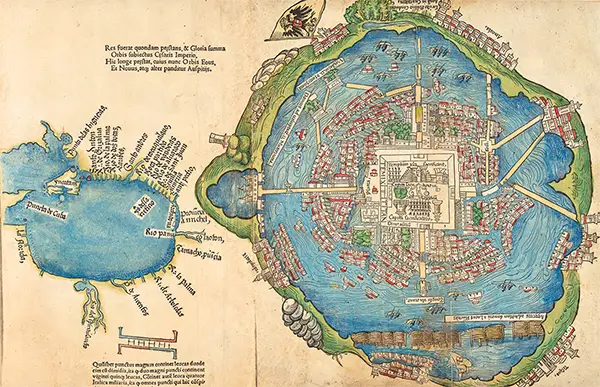

Three causeways connected the island to the western shore of Lake Texcoco. The causeways ran north, east, and west, and the people laid out the city in a grid pattern. As the population grew, residents embarked on land reclamation projects to provide more opportunity for living areas and growing areas. At its height, the city–which was divided into four zones, each of which contained 20 calpullis (districts)–covered more than 5 square miles. The residents soon implemented all manner of geographic enhancements. Innovative techniques such as canals, dikes, irrigation, and terracing helped the Aztecs develop an efficient agricultural system. A Stone aqueducts connected to springs originating in nearby hills brought fresh water into the city, to accommodate the people's habits of bathing daily (and, sometimes, twice a day). The people constructed a number of wooden bridges that allowed them to cross from one causeway to the next; builders made the bridges so they could be removed to make way from boats or to protect from attacks.

At the heart of the capital city was the ceremonial area, home to the 90-foot-tall Templo Mayor (Supreme Temple) and to many other religious and otherwise important buildings. Two giant temples featured atop the flat-topped pyramid of the Templo Mayor. The Aztec pantheon featured hundreds of gods, and temples dedicated to many of these dotted the area. Dominating the central area as well was the palace of the Huey Tlatoani (Supreme Ruler), which boasted 100 rooms, in which stayed ambassadors and other visitors to the city. Nearby was the tlachtli, the court on which Ullamalitzli, the Aztec ball game, was played. Also in the central area were an aquarium and a botanical garden. The population grew, as did the size and influence of the Aztec Empire. Many sources estimate the highest population of Tenochtitlan at about 200,000; at the time, few cities in the world were larger. All of that changed when Hernán Cortés arrived, at the head of a force of armed warriors that was a combination of his fellow Spaniards and members of a neighboring tribe, the Tlaxcala. The Aztecs' final emperor, Moctezuma II, welcomed Cortés, but the Spaniard did not return the favor. The Spaniards arrived in 1519 and, two years later, conquered the Aztecs, laying waste to Tenochtitlan and to the rest of the empire, through a combination of superior weaponry and firepower and the spreading of European diseases for which the Native Americans had neither immunity nor cure. Cortes, once he had eliminated the Aztecs as a threat, ordered Tenochtitlan razed; on top of its ashes arose Mexico City.

|

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White

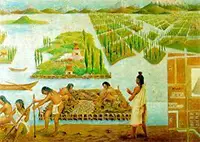

standout feature of the layout of Tenochtitlan was the chinampas (floating gardens), which were rafts of trees and mud. On these grew all manner of crops, including avocados, beans, corn (known as maize), potatoes, squashes, and tomatoes. Filling meat needs were hunters of local animals, such as armadillos, coyotes, rabbits, snakes, and turkeys. One particularly valued product was cocoa beans, which were used to make chocolate (which comes from the word chocolatl).

standout feature of the layout of Tenochtitlan was the chinampas (floating gardens), which were rafts of trees and mud. On these grew all manner of crops, including avocados, beans, corn (known as maize), potatoes, squashes, and tomatoes. Filling meat needs were hunters of local animals, such as armadillos, coyotes, rabbits, snakes, and turkeys. One particularly valued product was cocoa beans, which were used to make chocolate (which comes from the word chocolatl).