The Spanish Inquisition

Part 2: Facts, Figures, Horrors

Perhaps the most famous Inquisitor was Tomás de Torquemada, who served as the Grand Inquisitor of the Spanish Inquisition. He encouraged people in Spain to spy and inform on their friends, neighbors, and even members of their own family. All of this was possible because the Inquisitors guaranteed anonymity for people who gave evidence against others.

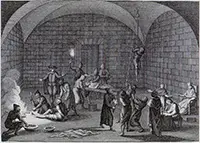

An accused person would face trial before a tribunal, which contained one or more judges. The accused had no lawyer or anyone to help in the defense. Some people who would otherwise have stated in public that an accused person was not guilty of the alleged crimes, but so stating could also throw suspicion of heresy on the "defense witness," leading to another tribunal considering another case. The prosecution, meanwhile, could have as many people as the tribunal allowed. Family members routinely testified against their own flesh and blood. Another common occurrence was the testimony of criminals, pointing the finger at an accused person in exchange for, perhaps, a lighter sentence. Tribunals sometimes made similar offers to others accused of heresy. Both Aragon and Castile had permanent tribunals. As well, in the more well-known incidences, Inquisitors traveled the country. When they arrived, they would announce a meeting at the local church and say that all in the city or town were required to attend. At that meeting, an Inquisitor would give a sermon, or religious message, and then issue a warning that anyone who was found to be a heretic but had not admitted it would be severely punished. The idea of this Edict of Grace was to get people to admit publicly that they had spoken out against the Catholic Church. Many people who confessed to heresy in this way were shown leniency; these people were told to do penance, such as helping other people or helping with whatever the Church needed, including the contribution of money. One form of penance was the donning of a hairshirt and keeping it on for a number of days, to ensure that the irritation caused by the contact between the person's skin and the animal hair of the hairshirt would remain the person to keep the faith. The people would be given a period of 30–40 days in which to come forward with confessions; after that, the tribunals, trials, and punishments began. One strategy that Inquisitors used to convince accused heretics to confess was the use of torture. A papal bull issued in 1252 by Pope Innocent IV had allowed such practices, but torture was supposed to be as a last resort. As well, torturers were not supposed to spill the blood of the people being tortured. Among the methods of torture used by the Spanish Inquisition were these:

The tribunal didn't accept a confession given during torture because the Inquisitors knew that people would often say anything just to stop being tortured. A common practice was for torturers to record the details of an accused's confession given while being tortured. Then, after the torture had stopped, the accused would have an opportunity to confirm or deny the heresy. Confirmation led to punishment; denial led to, in many cases, more punishment. Punishment could take a number of forms. People found guilty of heresy by the Inquisition could be forced to be a monetary fine, perhaps large. A common penalty was the confiscation by the state of property owned by the accused. Others found guilty were beaten in public.  In many cases, people who confessed to heresy were executed. Such an execution was commonly called an auto-da-fé (act of faith), and many of these executions were public. A common method of execution was burning the accused alive, by tying him or her to a wooden stake, often complemented by hay or brush or something else that burned quickly, and then setting it alight. The Inquisitors intended such public spectacles to frighten people into keeping the faith and/or confessing to heresy. Under the reign of Torquemada, some sources say, the Inquisition put to death about 2,000 people by burning them at the stake. The Inquisition, largely under Torquemada's guidance, raged for the rest of the 15th Century. Under his successor, Francisco Jimenez de Cisneros, the hysteria eased. It wasn't just in Spain, either. As Ferdinand took over more territory, he sent Inquisitors there. Tribunals appeared in Sardinia and Sicily, taken by Aragonese forces in the early 16th Century. The New World was not exempt: Tribunals appeared in what is now Mexico City and what is now Colombia. Under the rule of Charles V (who as, Charles I, was the first King of all Spain), the Inquisition took the form more of stamping out Protestantism. One of the more famous victims during this time was Bartolomé de Carranza, who at one time was one of the top religious officials in the country. Suspicions of sympathizing with Protestants resulted in his arrest and imprisonment; he died after 17 years of incarceration. The last person to be burned at the stake for confessing to heresy died in an auto-da-fé in 1731. In all, the number put to death by the Inquisition is thought to be in the tens of thousands and the number prosecuted is thought to have exceeded 150,000. In the 18th Century came the Enlightenment, a movement of profound change that affected many parts of life, in Spain and elsewhere in the world. As the 18th Century progressed, Church officials moved more toward censorship as a way of restraining the spread of thoughts and practices found to be anathema to Catholic teachings. In the earliest days of the Inquisition, Church officials had published lists of banned books. These continued to be published and consulted throughout Inquisition times. When Joseph Bonaparte was King of Spain in the early 19th Century, his government stopped the Inquisition. Subsequent Spanish monarchs brought it back. The Spanish Inquisition was an official policy until 1834, when Queen Isabel II ended it once and for all. First page > Setting the Stage > Page 1, 2 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White

The rack: the accused would have hands and feet tied or chained to rollers at either end of a horizontal wooden frame and then the person wanting the confession would turn the rollers, stretching the accused's joints in a very painful way. A variant of this was the Wheel: The accused was tied to a wagon wheel and then stretched over it.

The rack: the accused would have hands and feet tied or chained to rollers at either end of a horizontal wooden frame and then the person wanting the confession would turn the rollers, stretching the accused's joints in a very painful way. A variant of this was the Wheel: The accused was tied to a wagon wheel and then stretched over it.