Spain in the New World

Part 6: Liberation in the South As the years went by, Spanish leaders and soldiers solidified their hold on the former Inca lands, expanding their reach and defending what they had conquered against incursions by English and Dutch raiders. Cities like Lima and Trujillo got city walls. Port cities like Arica, Callao, Valdivia, and Valparaiso got fortifications and more ships. All of that occupation, forced resettlement, and forced religious conversion was not without resistance. Many times during the Spanish occupation, indigenous people rose up in revolt. Most of those were small in scale and not backed by weaponry enough to make a difference. One that succeeded in South America was led by Juan Santos Atahualpa, who in 1742 set off a rebellion of the Ahaáninka people that claimed a significant amount of land, repulsed a number of Spanish military expeditions to repress it, and ended only when the rebellion leader himself disappeared, in 1752. Another well-known successful rebellion was that led by Túpac Amaru II, who struck back at Spanish forces in and around Cuzco in 1780 with a force of tens of thousands and held out for more than a year; the rebellion continued for a year after his capture and execution. In the 18th Century came large-scale changes in administration. In 1717, the Crown created the Viceroyalty of New Granada, from the former Colombia, Panama, Venezuela, and parts of Ecuador, Guyana, and northern Brazil. In 1776 came the Viceroyalty of the Rio de la Plata, from what is now Argentina, Bolivia, Paraguay, and Uruguay.

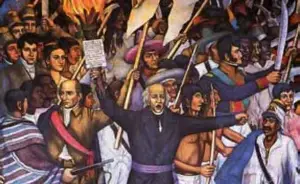

Spanish rulers and soldiers still had a large amount of weapons and ammunition in the early 19th Century. What the lower three classes had was a large number of people who were increasingly expressing a passion for going their own way. Inspiring them was the Virgin of Guadalupe, an indigenous patron saint whose skin color was not white. Depictions of her appeared on banners borne by those in rebellion. All of this came to a head in 1810, when a plea from a priest gave way to a full-blown revolution. Those in rebellion had access to enough weapons and enough manpower and money to keep reoccupation at bay and, instead, turn the tide on the Spanish, taking control of large cities like Acapulco and Oaxaca. The rebellion gained steam and purpose and eventually, after 11 years of conflict, resulted in the independence of Mexico The independence of Mexico meant that the Spanish possessions in what is now the U.S. left the Empire as well. Central America seceded in 1823. For all intents, New Spain was no more.

As happened in Mexico, a drive for independence from Spanish rule began in the south in 1810 and eventually succeeded. Led by Joséde San Martin, Simón Bolivar (right), Thomas Cochrane, and others, the Expedición Libertadora occupied Lima, in July 1821. A week later, on July 28, Peru was independent. That was a technicality, of course, since Spain hadn't given up on ruling the rest of the Viceroyalty of Peru. The fighting continued for another three years, with the final two revolutionary victories coming at the Battle of Junin, on Aug. 6, 1824, and the Battle of Ayacucho, on December 9 of that same year. The final capitulation came from Viceroy José de La Serna, whom revolutionary forces had captured in the aftermath of the battle. Thus ended the Viceroyalty of Peru. Bolívar's efforts helped bring about the independence of other states, including Colombia, Ecuador, Panama, and Venezuela. Out of Peru came the country named for El Libertador, Bolivia. Next page > The Last of an Empire > Page 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White