The Irish Potato Famine

The Irish Potato Famine killed hundreds of thousands of people in the mid-19th Century and forced thousands more to seek a life new in a new home. The potato was not native to Ireland. Many historical accounts relate the story of its introduction into the Emerald Isle after England's Sir Walter Raleigh brought it back from the New World, about 1570.

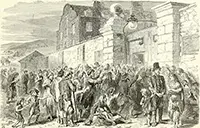

The potato came to be a staple of Irish agriculture, producing large harvests in the predominantly damp climate while requiring relatively little work to plant or harvest. Estimates are that by 1840, as many as one-third of the Irish population considered the potato as the primary source of food. In September 1845, the arrival of the potato blight changed Irish civilization. It was a tiny fungus called Phytophthora infestans. Striking quickly and savagely, the blight killed off one-third of the Irish potato crop in a year and three-quarters of the remaining crop in each of the next two years. People who Most of the areas that were the hardest hit were in the south and west, in which people spoke mostly Irish. The native term for this time was An Drochshaol, which in English approximated "the hard time." Some responded by taking to the streets, in some cases even breaking into food stores in search of daily sustenance. The number and severity of the death toll had a handful of causes:

At the same time, farmers in Ireland grew beans, oats, peas, wheat and shipped it to England. Other sizable export goods from Ireland to England included livestock such as oxen, pigs, and sheep. Butter, in particular, continued to be a large export product during the Famine. Many Irish people worked these farms and were paid a pittance, not enough to buy the food that they produced.

The response from the U.K. government of Lord John Russell was slow and insufficient. An 1834 law had created a workhouse system for the poor. When the potato blight hit, the number who had no money to their name was many times more than could be accommodated by the workhouse system. The U.K. Government did repeal the Corn Laws, removing the artificial hold on the high price of grains. As a result, more poor people could afford staples like bread. Donations poured in from other countries, notably Russia and the U.S. (One of the prime drivers of American charity toward Ireland at this time was noted lawmaker Henry Clay. People continued to die in droves, however. The Great Potato Famine was declared over in 1852. By that time, the damage was done. The potato blight was more widespread, although Ireland was hit the hardest. About 100,000 people died as a result of similar blight elsewhere in Europe in the 1840s. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White

couldn't afford to plant or eat much else struggled with starvation and disease. A great many died. Historians differ on the total number of deaths during this dark time. Conservative estimates number 500,000; some accounts number the dead at 1.5 million. Another 1 million are thought to have fled the country, many going to America and Canada.

couldn't afford to plant or eat much else struggled with starvation and disease. A great many died. Historians differ on the total number of deaths during this dark time. Conservative estimates number 500,000; some accounts number the dead at 1.5 million. Another 1 million are thought to have fled the country, many going to America and Canada.