The Huns

The Huns were known for wearing their hair parted down the middle and their beards parted as well. They also wore colorful ribbons in their hair and their beards. The Huns were most at home on horseback, roaming the countryside, their flocks of sheep in tow. Naturally, they were excellent horse riders and powerful enemies on horseback.

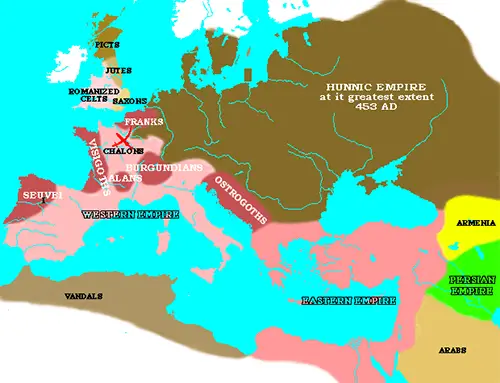

The Huns had migrated from Central Asia into Europe as early as the 2nd Century. They had conquered the Alans in the latter half of the 4th Century and then targeted the Goths, who, in turn, left their homes in hopes of finding refuge within the Roman cities in the Danube River valley. Other peoples, among them the Burgundians, also fled the conquering Huns. Roman forces suffered a grave defeat at the hands of the Goths at Adrianople in 378. Roman sources record employing Huns as mercenaries and auxiliaries in the 380s and 390s. In the last few years of the 4th Century, Hun warriors launched a pair of large raids into Roman territory, mainly in the Balkans. The first Hun leader named in Western accounts was Uldin, who led a large-scale foray into the Eastern Roman Empire in 408. Roman forces repulsed the attacks, and the Huns retreated beyond Roman borders. Two years later, Rome was again employing Huns in their ranks, this time to fight against Alaric, the Visigoth leader who engineered the sack of Rome in 410. Leading the Huns in the 420s were brothers Octar and Ruga. Among their accomplishments was an agreement with Rome by which the latter agreed to pay an annual tribute in return for the former's keeping the peace. Octar died in 430. After the death of King Rugila in 434, the Huns named his nephews, the brothers Atilla and Bleda, as co-rulers. The following year, they agreed to the Treaty of Margus, an amplification of the tribute engineered by their uncles. Bleda died in 445, and Attila became sole ruler of the Hun kingdom.

A strong, tough leader with a magnetic personality, Attila had little trouble convincing a number of "barbarian" tribes to ally with him against Rome. Attila was also a brilliant commander and had such success in such a short time that his enemies termed him the Flagellum Dei ("Scourge of God"). He achieved the possession of an empire that stretched from what is now France into central Asia and south through the Danube valley. The Huns were a feared cavalry force, capable of performing feats of great daring and skill while riding at top speed. They fought with bladed weapons, slashing and stabbing in a blur; they also often used a lasso-like weapon to disarm or entangle their opponents. In the thick of battle, their horses also joined in the fray, biting and kicking any enemies who came near. Protecting the riding Hun was usually some form of leather armor; some warriors had a kind of chain mail. Many warriors wore a cone-shaped metal helmet. The Romans had found the Huns willing allies in struggles against the Franks and Visigoths. The Roman general Flavius Aetius had enlisted the aid of Attila in order to conquer the Burgundians. The alliance did not hold. The Roman Emperor Theodosius II had paid Attila a large sum of money not to attack any more. For a time, the two armies fought other foes, with the Romans defending against the Vandals in Sicily and North Africa and the Huns targeting the Sassanid Empire in the east. Things didn't go so well for the Huns, and they retreated to the Great Hungarian Plain.

Attila, seeing an opportunity, marched back into Roman territory, sacking towns along the River Danube. Again Theodosius paid Attila to forestall the attacks; again Atilla went back on his word. A pair of new emperors refused to pay Attila any more money, since they reasoned that he couldn't be trusted not to attack anyway. Incensed, Attila gathered an army a half million strong and invaded Gaul. The Huns had great success in ravaging the countryside and capturing and sacking cities. A desperate Aetius, Attila's onetime ally, rallied the Roman troops, allying them with Celts and Franks, and Visigoths, and met the Huns head-on. The result for Attilla was a resounding defeat at Chalons, in 451. (This is often referred to as the Battle of the Catalaunian Fields.)

The following year, Attila led his men into northern Italy. Ostensibly, Attila was in search of a wife. Honoria, the sister of the emperor Valentinian III, had written to Attila, asking for his help in getting her out of an arranged marriage; she had included her engagement ring along with the note. Attila considered this a marriage proposal and said that he would marry her if she brought a dowry of one half of the Western Roman Empire. Valentinian discovered the communications and sent his own to Attila, telling him it was all a big mistake. Attila, whether he seriously considered the idea of marrying the emperor's sister or not, invaded Italy anyway, along with 200,000 men. The Huns sacked the cities of Aquileia and Milan, among other conquests, sending people streaming out of villages and towns. They did not, however, attack Rome. Historians differ on the reasons for this. Whatever the reason, the Huns returned home. In 453, Attila married again, to a young woman named Ildico. (He had earlier been married to a woman named Kreka.) The newlyweds celebrated with great indulgence of food and drink. The next day, Attila was dead, from a burst blood vessel. His shocked men buried his body in a river bed, first diverting the river and then reverting it to cover the burial spot. Attila's death created a power struggle between his many sons. One son, Dengizich, restored some sort of order in the 460s. His death at the end of that decade was ostensibly the end of the Huns as a united people. They lived on in various capacities, within the Roman Empire and without. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2025

David White

The Huns were a Eurasian people who directly and indirectly played a role in the decline of the Roman Empire. The most famous of the Huns was Attila, who engineered many great victories for his people.

The Huns were a Eurasian people who directly and indirectly played a role in the decline of the Roman Empire. The most famous of the Huns was Attila, who engineered many great victories for his people.