Herodotus: Greece's First Historian

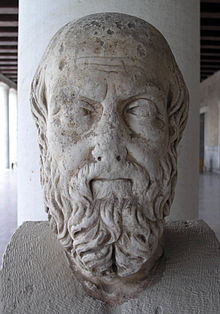

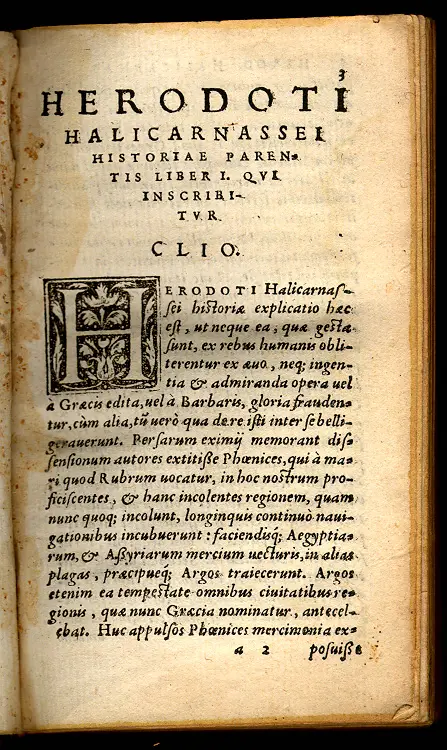

Herodotus is regarded by many to be the "Father of History," for his famous work The Histories, an account of the causes and particulars of the Greco-Persian Wars. However, his work also includes many fanciful tales, which has led others to term him the "Father of Lies." One thing is for sure: We know a lot more about the Greek world, the Persian world, and the world around both ancient civilizations from what Herodotus wrote down than we ever would have if he had not been compelled to scrawl on scrolls with an eye toward posterity. The beginning of his nine-volume work states his case, that he wants to preserve the memory of the past by recording it in written form and in some way explore how the two greatest powers in that part of the world in that time came into intense mortal combat for such a sustained period of time. On its face, the Histories are a chronological narrative of the reign of four Persian kings: Cyrus the Great, Cambyses, Darius the Great, and Xerxes the Great. In amongst all of the descriptions of Persian royalty and warfare and religions and

legends are descriptions of life, worship, trade, and war in other civilizations as well, most notably his own. Herodotus was born in Halicarnassus, in Asia Minor, in 484 B.C. Little of his life is known other than the details he includes in his writings. He writes of taking part in a plot to overthrow the ruling dynasty of his home city. The plot was unsuccessful, and he was exiled to the nearby island of Samos. He never returned to Halicarnassus, but he did travel elsewhere in the Mediterranean world, as evidenced by his many first-hand accounts of life and goings-on in Egypt and other Persian possessions. He also included extensive descriptions of animal life in his narratives. In 431, the Peloponnesian War began. This spurred Herodotus to write his Histories. It is quite possible that he had written records already, of his various travels and interviews with people of other lands. The result originally filled several very long scrolls.

The first volume tells the story of Cyrus. The second and third volumes relate events in the life and reign of Cambyses. The third volume ends with the ascent of Darius, whose story continues through volumes four, five, and six. Xerxes rounds out the Histories in volumes seven, eight, and nine. (Herodotus did not intend his work to be so divided; the division was performed later at the Great Library of Alexandria.) The overall theme Herodotus presents is that of an inevitable conflict between two large world powers, whose continual expansion quite naturally brought them into conflict with each other. This might seem quite natural to today's readers; however, in those days, such thinking wasn't normally practiced. The Greeks excelled at inquiry, invention, and introspection; but Herodotus was the first to turn all of his research into an overarching narrative, one that contained details mundane and fanciful. A wealthy and well-learned man, as evidenced by his ability to travel and to quote widely from known literature, Herodotus also includes references to the gods and their caprices. One of his main arguments for the eventual defeat of the Persian Empire was the pride and haughtiness of the emperors, who thought themselves equal to the gods: "The gods loves to punish whatever is greater than the rest." He writes of many people, places, and things that might seem ludicrous to modern readers. In some instances, based on what was discovered later, what he was reporting complete fiction. Other stories have turned out to be quite true, despite the objections of initial readers. As an example, he writes of some ancient Phoenician mariners who reported seeing the Sun on the starboard side as they traveled west. This would certainly be the case if the ships had sailed around Africa counter-clockwise: As they rounded the southwest corner of the continent, the Sun would be on their right. He is also up front about presenting multiple versions of a story and then asserting which version he thinks has the most veracity — exactly the sort of skill prized by historians and journalists. That he included so many interpretations and so many folk tales played a part in some critics' branding him a teller of falsehoods.

The Histories end with the victory of Greek forces over the armies of Xerxes at Salamis and Plataea. The narrative stops abruptly, suggesting to many historians that Herodotus died before he was finished writing what he wanted to write. From certain clues gleaned from the text, one theory is that he died sometime before 413. Other sources definitely state his death year as 425. Despite the abrupt end and the suspect nature of many of the stories, the Histories remain the product of one of the world's first historians, to whom many subsequent chroniclers continue to turn in their study of ancient times. Some sayings from the Histories:

|

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White

Herodotus was as much a geographer as a historian, presenting detailed descriptions of the mountains, waterways, boundaries, and population patterns of the various ancient lands to which he or people he talked to had traveled. The Histories feature many detailed accounts of farming techniques, including a not-quite-on-the-mark theory for the annual flooding of the Nile River: He thought that the desert winds affected the passage of the Sun over that part of the world, creating melting snow that flowed downstream and overwhelmed the Nile Delta.

Herodotus was as much a geographer as a historian, presenting detailed descriptions of the mountains, waterways, boundaries, and population patterns of the various ancient lands to which he or people he talked to had traveled. The Histories feature many detailed accounts of farming techniques, including a not-quite-on-the-mark theory for the annual flooding of the Nile River: He thought that the desert winds affected the passage of the Sun over that part of the world, creating melting snow that flowed downstream and overwhelmed the Nile Delta.