The French Revolution

Part 7: War Without, Terror Within In the meantime, France was at war with Austria. On Aug. 17, 1791, Prussian King Frederick William II had issued the Declaration of Pillnitz, which asked other monarchs of Europe to help restore the French king to his absolutist throne. This served to heighten tensions within the French government. In fact, many people in France wanted to take their republican movement outside French borders. A significant number of people in the Low Countries (what is now Belgium and the Netherlands) appealed to France to help them achieve the same sort of revolution within their borders. As well, the French Army faced enemies from within. Queen Marie Antoinette was from Austria. She sought to prevent a complete elimination of the monarchy by embracing the efforts of Austria and others in restoring her husband to her former power; to do so, she obtained her army's war plans and passed them to the Austrian war department. Back in Paris, the National Convention had been overrun by republican fervor, such that many were blaming the king for the early defeats and absolving him of any credit for the recent victories. More ominously, the Convention called the king to trial, on Dec. 11, 1792. He had been arrested after the August storming of the Tuileries and kept in the Temple. When the government abolished the monarchy, he became known as Citoyen Louis Capet. The main charge was treason, stemming from his attempt to flee the country in June 1791. The Convention also charged the king with attempting to ally with France's enemies in order to engineer an overthrow of the government and reinstate himself as the supreme head of the state. The discovery of an iron chest containing compromising correspondence validated this charge.

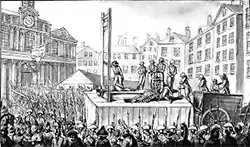

Many republicans in the Convention wanted the end of the monarchy in any form and many who wanted the king dead. Foremost among these was Maximilien Robespierre, who declared that, "Louis must die so the nation may live." After a series of spirited debates, the Convention voted to convict the king. That vote was unanimous. The debate then turned to how to punish the king. That ended in a vote as well, and many deputies voted against execution. However, a majority did, and so the king indeed was put to death, on Jan. 21, 1793. He was 38. Among his last words were these: "I die innocent of all the crimes laid to my charge; I Pardon those who have occasioned my death; and I pray to God that the blood you are going to shed may never be visited on France." As many moderates had warned, the execution of the king united the rest of Europe in opposition to the Republic. The First Coalition came about when France declared war on Great Britain, the Netherlands, and Spain and then the Holy Roman Empire, Naples, Portugal, and Tuscany declared war on France. To fight this new consortium, the National Convention introduced a large conscription, swelling the French ranks even more. A considerable number of men in the Vendé region of the country refused to report, others joined in, and the dispute became violent. To deal with internal enemies, the National Convention in March 1793 set up the Revolutionary Tribunal, a judicial body tasked with examining people charged with insurrection. By this time as well, the Convention had delegated much of its authority to a number of committees, the most prominent of which was the Committee of Public Safety, which the Convention created on April 6. During its first few weeks, the Committee was a model of revolutionary intent and action, focusing on shoring up the war effort and ensuring that no internal uprisings derailed the country's new path toward egalitarianism. Also during this time, the members of the Committee crossed the political spectrum, involving a mix of moderates and radicals, all of whom had to work together in order to effect the kind of change that they all wanted to see. Leading the way at this time was Georges Danton.

In time, however, as the country's war fortunes worsened, radicals gained control of the Committee and, still in secret, put themselves more and more in charge of more and more elements of society. Maximilien Robespierre (right) won election to the Committee on July 27, 1793, and maintained his seat until his death. The same was true of other radicals such as Louis Saint-Just and Lazare Carnot. To Bertrand Barére the Committee left the writing of new laws and the reporting (more selectively as time went on) to the National Convention. Robespierre had demonstrated his power to mobilize public opinion by organizing a June 2 "visitation" of the Convention by hundreds of sans-culottes, to reinforce the idea that the Girondists (whose political enemies were the Montagnards) should be ousted from the Convention.

As more and more radicals controlled actions in the Convention, the Convention itself gave more and more power to the Committee of Public Safety. On Sept. 14, 1793, the Convention handed over to the Committee the power to appoint deputies to other committees. On September 17, the Convention created the Law of Suspects, which greatly expanded the way in which people could be declared targets for arrest and punishment; following that was the Law of the Maximum, which set price ceilings in order to crack down on people engaged in price gouging. These measures concentrated in the Committee more and more power. This expansion of power resulted in more and more executions of so-called enemies of the state, notable among them Queen Marie Antoinette and the Girondin leader Jacques Brissot. On October 10, the Committee declared itself in charge of all of the government except the National Convention, to which the committee still nominally reported once a week. By this time, the leaders of the Committee were Robespierre, Saint-Just, and George Couthon. In reality, they were running the country and directing the Reign of Terror. The Committee's takeover of the government was complete on Dec. 4, 1793, when the Convention passed the Law of 14 Frimaire, or the Law of Revolutionary Government. Also known as the "Constitution of the Terror," this law gave to the Committee supreme executive power.

One of the main aims of the Reign of Terror was to eliminate enemies of the state. With the December takeover, the Committee had the power to decide who were enemies of the state. Even though Jacques Hébert and his followers had supported the Reign of Terror and, in particular, the Law of Suspects, the Committee declared them outlaws, as it were, and sent Hébert and the other leaders of his movement to the guillotine, in March 1794. This followed a pattern of the Committee's identifying former allies as enemies and then dispatching them. Another group targeted and dispatched were the followers of Georges Danton. The famous revolutionary himself was one of those convicted by the Tribunal and executed, in April 1794. In June 1794, the Committee created the Law of 22 Prairial, which put a structure around the process of identifying and punishing enemies of the state. Prisoners were denied lawyers, and witness testimony all but disappeared. Monumentally under this law, the punishment for all crimes delineated was death. This dramatically increased the number of state-directed deaths. In effect, it was nearly a straight line from arrest to execution. In the 13 months before the passage of this law, the Revolutionary Tribunal had delivered 1,220 death verdicts. In the first 49 days after the passage of this law, the number of executions was 1,376.  As the summer of 1794 continued, dissent grew inside the Committee. Robespierre and Saint-Just found themselves increasingly isolated, even though they retained enormous power. Recent military victories had convinced many that the Committee no longer had the country's best interests at heart and was overstepping the bounds of its original purpose, that of defending the country from foreign enemies. Robespierre gave a speech to the National Convention on July 26, 1794, calling for purges within the government's various committees. The next day, Saint-Just rose to speak at the Convention but didn't finish. He found himself at the center of a series of accusations with which he would have been all too familiar. Also targeted was Robespierre. The pair were arrested, along with a handful of their supporters, but not until they had taken refuge in the Hôtel de Ville and started planning an armed rebellion. Their attempt at insurrection failed. The leaders of the Terror were themselves sent to the guillotine, on July 28, 1794. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White