The French Wars of Religion

Part 2: Later Struggles The French Wars of Religion were not a constant struggle. Tempers flared and weapons clashed off and on; periods of peace punctuated the periods of conflict.

Religious violence flared up again in 1567. A number of Huguenots tried to capture the king and members of his family at Meaux. This plot, too, was foiled. Angry Huguenots in Nîmes killed Catholics on the Christian holiday of Michaelmas, an incident that came to be known as Michelade. More battles followed, and the king in 1568 declared another peace. Catholic militants unhappy with the terms of that peace resumed the fighting, and the war dragged on, this time involving forces from England, Navarre, Spain, and Tuscany. Charles IX married in 1570, to Elisabeth of Austria; they had a daughter, Marie Elisabeth of Valois. In that same year came the Peace of Saint-Germain-en-Laye, after which Charles increasingly took advice from Admiral Gaspar de Coligny, a Huguenot leader.

In an attempt to keep the peace, the Huguenot Henry of Navarre married the Catholic Margaret of Valois, sister of the king, on Aug. 18, 1572. The marriage took place in Paris, a Catholic stronghold. Thousands of Protestants traveled to the capital for the wedding. A week after the wedding, in August 1572, the Duke of Guise, a leader of the Catholic war effort, killed Coligny, a Huguenot leader. The violence that followed last five days. Catholics by the thousands targeted Huguenots by the thousands, in what came to be called the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre (right). Estimates of the dead range widely, from a few thousand to tens of thousands. Huguenots responded again with warfare, and Catholics joined in the fray. Charles in 1573 issued the Edict of Boulogne, which granted religious freedom and amnesty to the Huguenots living in France. This angered Catholics, and the violence continued off and on for months.

Charles died in 1574, and his younger brother Henry took the throne. Named commander in chief of the royal armies in 1567, Henry had led royal troops against Huguenot forces at the Battles of Jarnac (right) and Moncontour, both in 1569. He had further angered Protestants by ordering the execution of the Protestant leader the prince of Condé, who had been captured at Jarnac. Henry tried to keep the peace by issuing the Edict Beaulieu, which made it possible for Huguenots to follow their own worship procedures in public. Catholics in France and elsewhere were none too happy with this pronouncement; the powerful French Catholic Henry I, Duke of Guise, formed the Catholic League as a result. Henry had a brother who was younger than he was. When Henry became king, that brother, Francis, became the Dauphin. Francis died on June 10, 1584, and Henry had no children. Thus was named Henry of Navarre as Dauphin. Henry had a bloodline connection to the throne, as a descendant of King Louis IX; he was also married to Margaret of Valois, sister of the king. However, Henry of Navarre was also a Protestant and, to Catholics the worst kind, a Huguenot.

The Wars of Religion dragged on, with no end in sight. Neither side was willing to endorse a truce or compromise unless it meant complete happiness for that particular side. On May 12, 1588, a Catholic force under the leadership of the Duke of Guise marched into Paris, in what came to be called the Day of the Barricades. King Henry III fled the city. A few months later, on December 23, the king invited the Duke of Guise to a meeting at the Château de Blois. Also invited was the duke's brother, Louis II, Cardinal of Guise. Unbeknownst to either brother, they had walked into a trap. Henry's men killed both brothers and also imprisoned the duke's son. The outrage in Paris was palpable: The king had ordered the execution of two very popular leaders and two very popular Catholics. He found himself at opposition with Parlement as well and retired to Tours, where he set up his parliament. He also allied himself fully with the Dauphin, who commanded a considerable armed force. The two Henrys banded together and marched on Paris. On Aug. 1, 1589, the king was staying at Saint-Cloud, preparing for battle. He died at the hands of an assassin, and Henry of Navarre became King Henry IV. Henry had become King of France, after he promised to convert to Catholicism. He is said to have remarked, "Paris is well worth a Mass." He finally did so a few years into his reign and was officially crowned King Henry IV of France on Feb. 27, 1594.

Before that, he had to fight for his right to rule. Paris remained a stronghold of the League of Nobles, and so Henry left it to them. He and his army fought on, chalking up victories at Arques (right) and Ivry, in 1589 and 1590, and capturing Chartres and Noyon. They were less successful at besieging Paris in 1590 and Rouen in the long months of 1591–1592. Finally, in July 1593, Henry announced that he would embrace Catholicism (again). The conversion removed much of the resistance to his rule internally; Spain remained as an enemy. A declaration of war came in January 1595; by June, Henry's forces had defeated the Spanish in Burgundy. A further seizure of Amiens, in 1597, all but ended the conflict. The Peace of Vervins, signed the following May, stopped Spanish intervention.

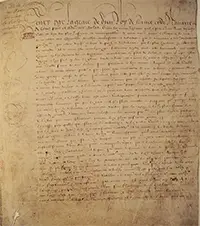

A month before, in an effort to head off the continued violence, Henry had issued the Edict of Nantes (right). This, more than any victories won by either side, precipitated the end of the Wars of Religion. In this pronouncement, Henry declared that Catholicism was the French state religion while also granting religious freedom to Protestants. First page > Early Struggles > Page 1, 2 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White