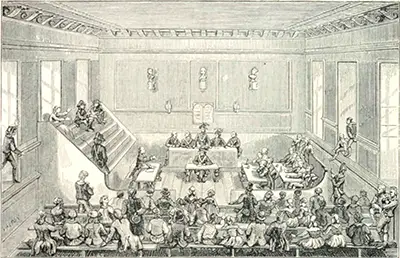

The Revolutionary Tribunal

The Revolutionary Tribunal was the judicial arm of the Reign of Terror in France. Eventually four panels, the Tribunals sent thousands of people to their deaths. Jean-Baptiste Carrier proposed the idea of such a tribunal in a speech to the National Convention in March 1793. Expressing whole-hearted support was Georges Danton, who said, "Let us be terrible to dispense the people from being so." Making up the Revolutionary Tribunal were five judges, a 12-man jury, a public prosecutor, and two substitutes. The National Convention appointed those people and the Tribunal's decisions were final. The names of people to be examined by the Tribunal came from the Committee of General Security and the Committee of Public Safety.

The most well-known public prosecutor involved with the Revolutionary Tribunal was Antoine Fouquier-Tinville (left). From the beginning, he followed French law to the letter, giving each person accused a preliminary interrogation, taking a deposition, and then presenting both evidence and witnesses

Under pressure, the National Convention on Sept. 5, 1793, created three more Tribunals and expanded the number of judges to 16 and the number of jurors to 48. Another measure that chipped away at the rights of the accused was the Law of Suspects, passed on September 17. This law greatly expanded the conditions under which people could be declared enemies of the state. For example, any who had not "constantly demonstrated their devotion to the Revolution" could be arrested and charged with treason. The punishment for being convicted of that crime was harsh from the start; it eventually became death.

The Revolutionary Tribunals quickly became vehicles for getting rid of political opponents. Foremost among the early victims was the queen, Marie Antoinette, who was declared guilty despite the prosecution's providing any reliable evidence to back up its claims of betraying the country. In June 1794, after an attempt on the life of National Convention members Jean-Marie Collot d'Herbois and Maximilien Robespierre, the Committee of Public Safety created the Law of 22 Prairial, which put a structure around the process of identifying and punishing enemies of the state. Prisoners were denied lawyers, and witness testimony disappeared. Monumentally under this law, the punishment for all crimes delineated was death. This dramatically increased the number of deaths. In effect, it was nearly a straight line from arrest to execution. In the 13 months before the passage of this law, the Revolutionary Tribunal had delivered 1,220 death verdicts. In the first 49 days after the passage of this law, the number of executions was 1,376. That was only the Paris Tribunal. The total thought to have been executed exceeded 15,000. After the guillotine claimed Robespierre and others who had led the Reign of Terror, the Convention kept the Tribunals in order to prosecute others who had prosecuted the deathly agenda. Carrier, who had proposed the Tribunals, found himself sentenced to death and was summarily executed, as were former Tribunal President Martial Herman and former chief prosecutor Fouquier-Tinville. The National Convention disbanded the Revolutionary Tribunals on May 31, 1795. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White

before a meeting of the judges in order to bolster the case for guilt. Many radicals complained at the slowness of the process. Others grumbled at the number of acquittals. One of the most famous of those acquittals was that of

before a meeting of the judges in order to bolster the case for guilt. Many radicals complained at the slowness of the process. Others grumbled at the number of acquittals. One of the most famous of those acquittals was that of