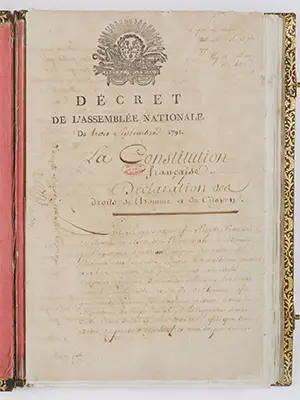

The French Constitution of 1791

The Constitution of 1791 was the governmental blueprint for France for a time, in the shadow of the French Revolution. When the Third Estate formed the National Assembly in June 1789, those gathered made it very clear that they wanted a constitution to be their governmental blueprint. On July 14, the day of Storming of the Bastille, the Assembly formed a Constitutional Committee and assigned to it 12 people.

In its first several weeks, the committee debated several key issues, among them the overall makeup of the government and the amount of power that the king should still have. Some, including the Marquis de Lafayette, favored a bicameral parliament, along the lines of those already in place in Great Britain and the United States. Others favored a unicameral, or one-house, legislative body. The Constitutional Committee recommended the former, and the Assembly approved the latter. The same was true with an executive veto: To the Constitutional Committee's recommendation of an absolute veto the full Assembly replied that along the lines of what the U.S. had–an executive veto that the legislature could override–was the way to go. The king could withhold his approval of a bill for up to five years; after that time, the Assembly could declare the law valid, even without the king's consent. Three members of the original Constitutional Committee were holdovers on a new committee, which had as its other five members citizens of the Third Estate. A main point of debate for this committee was the technical distinction of citizenship. The committee distinguished between active citizens, who were defined as males who were 25 or older and paid direct taxes that equated three days of labor, and passive citizens, who did some or none of those things. Women were not included in these distinctions; neither were slaves. The Committee decided in the end that the Constitution would apply to active citizens. The National Constituent Assembly in September 1790 created the Committee of Revisions to rule on whether the Assembly and its pronouncements could have the force of law and form the basis of a new form of government. They did so, ruling in the affirmative.

In the end, the Assembly presented a constitution to King Louis XVI, and he signed on, in September 1791. By that time, he had lost a large amount of whatever sympathy he had left by trying to flee the country. Still, he was the executive power provided for in the Constitution; the other two branches of government were the Legislative Assembly, a new body to replace the National Constituent Assembly, and the judiciary. Specifically, Title III reads thus:

The Constitution did contain certain privileges of and protections for the king:

The Constitution also required the monarch to do certain things: "On his accession to the throne, or as soon as he has attained his majority, the King, in the presence of the legislative body, shall take oath to the nation to be faithful to the nation and to the law." (Chapter II, Section 1.4) If the king did not comply within a month after being invited to do so by the Assembly, then, the Constitution, stipulated "he shall be deemed to have abdicated the throne." The same was the result if the king ordered an army to attack his own people or if he left the country and did not return when told to do so by the Assembly. Significantly, the Constitution went to say that after abdication, the king "shall be classed as a citizen, and such he may be accused and tried for acts subsequent to his abdication" (Chapter II, Section 1.8). The Constitution stipulated that the people had the power to elect a regent, if the king was not old enough to rule in his own right. The minority, according to the Constitution, was until the king reached the age of 18. The oath that the king was required to take was the same that was required of all government officials: I swear to be faithful to the nation, to the law, and to the King, and to maintain with all my power the Constitution of the kingdom, decreed by the National Constituent Assembly in the years 1789, 1790, and 1791. The legislature could constrain a king's warmaking powers, the Constitution said: "Throughout the course of the war the legislative body may request the King to negotiate peace; and the King is required to comply with such request" (Chapter III, Section 1.2). In fact, earlier in the same subsection: "If the legislative body decides that war is not to be made, the King shall take measures immediately to effect the cessation or prevention of hostilities." The Constitution also enshrined into law a handful of principal rights that the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen defined as "natural and imprescriptible," such as

|

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White