The Crusader States

The Crusader States were a handful of lands carved out of land seized by Western armies after the First Crusade. The four Crusader States, established around the turn of the 12th Century, were these:

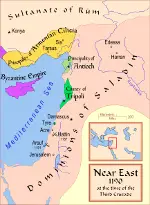

Together, the Crusader States comprised land in what is today Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, and Turkey. Pope Urban II launched the First Crusade at the Council of Clermont, issuing a call for a large army to retake land in what was known as the Holy Land from the Seljuk Turks, who had seized the land in 1087. An army exceeding 10,000 men invaded the Holy Land and retook much of what had been seized. To maintain influence in this part of the world, Crusader leaders set up the Crusader States. To help defend these territories, Crusaders encouraged the formation of military orders, including the Knights Hospitaller and the Knights Templar. The most valued of these new territories was the Kingdom of Jerusalem because it contained that city and a few others considered sacred by Christians. (Actually, Jews and Muslims shared this belief about the sacred nature of Jerusalem.) Among the other important cities were Acre, Caesarea, Sidon, and Tyre. Godfrey of Bouillon, on the most effective of the Crusader commanders, became the first king of this new Kingdom of Jerusalem. He had at his disposal a force of more than 2,000 soldiers. Ruling the County of Edessa was Baldwin of Boulogne. This was the largest of the Crusader States yet was secondary in importance to Jerusalem. Among the important cities in the County of Tripoli were the namesake, Tripoli, and Damascus. Raymond of Toulouse, whose army had captured Tripolis after a long siege, was the first ruler of this new territory. The Principality of Antioch had as its first ruler Bohemund, a Norman soldier. This territory had very close ties to the Byzantine Empire, through political and marital arrangements. The Crusader States rulers functioned very much as monarchies, although they routinely consulted nobles who gathered for council meetings, much like what went on various Western European countries. Jerusalem even had a regular public forum called a parlement, that the monarch tasked with making some decisions, particularly on foreign diplomacy. The Crusader States had levels of government resembling some of those found in Western Europe. The Court of Lieges ran legislative matters in the territories. One level of hierarchy below was the Court of the Burgesses, who looked after disputes between individuals. Each Crusader State also had its individual powerful Christian Church envoys. Crusader monarchs installed in positions of power people very much like themselves, so Westerners who spoke dialects of what is now French. Very few Turks and other Muslims living in these areas spoke that language; and, even though the new rulers were outnumbered in terms of population, they managed to hold on to their positions of power because they had the backing of the soldiers left behind and of the Western powers from which they had come. After the taking of this land and the creation of these territories, the vast majority of the Crusader forces went home. What followed for the Crusader States was a couple of decades of tenuous alliances–among one another and with their neighbors–. This had next to no effect on trade, which functioned much as before, as traders overcome language barriers by making things work along economic lines. Acre grew into a very powerful trading port. The Kingdom of Jerusalem thrived as an economic power and minted its own gold coins, a feat rare in those times. The victory of the Crusaders fragmented the Muslim defenders, and it took awhile for a leader to rise to prominence and secure the backing of others like himself. That Muslim leader was Imad ad-Din Zangi. Forces under his command led a monthlong siege of Edessa, the end of which was the sacking of the city by Zangi's forces, led by that time by his successor, Nur al-Din. Hearing of this, Western powers launched the Second Crusade, which was very much a disaster for the Crusaders. Nur al-Din turned back an invasion force bent on retaking Edessa and took Antioch as well. The Second Crusade ended with a whimper.

It wasn't long until an even more powerful and charismatic Muslim leader emerged, the famous Saladin. The Sultan of Egypt and Syria, he rallied great armies to his cause and struck back against the Western powers. Saladin's forces won a strategically important victory at the Battle of Hattin in July 1187 and then took Jerusalem itself in September. Other armies had seized most of the rest of the Crusader States by this time, and the fall of Jerusalem resulted in the launching of the Third Crusade. Crusading armies seized Acre but did not have resources enough to retake Jerusalem. The result was a newly established Kingdom of Jerusalem, with Acre as the capital; this kingdom did not contain Jerusalem itself. The Crusader States held on to varying amounts of their land for a number of years, some states more than others:

The fall of Acre in 1291 is generally considered to be the end of the Crusades. It was certainly the end of the Crusader States. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White