|

|

Ancient China: Early Civilizations to First Emperor

|

|

|

|

Share This Page

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Follow This Site

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Chinese civilization is one of the world's oldest.

As with other ancient civilizations, settlements in China arose near rivers. The first was thought to have arisen near the Huang He, or Yellow River. In the fertile flood plain of that river, some of the first Chinese people farmed, husbanded animals, crafted pottery, made tools and weapons, built dwellings, and set about improving their lives a little at a time.

Another early civilization sprang up along the Yangtze River. It is in that civilization that archaeologists have found the first evidence of cultivated rice, dating to 8,000 years ago.

As populations multiplied, civilizations spread out. People moved–at times for negative reasons, such as natural disaster, and at other times for positive reasons, such as a desire to explore more of the world around them. Through such explorations arose trade, not only with other Chinese people but also with other civilizations. As towns grew, so, too, grew walls and moats around them.

Xia Dynasty

The first dynasty to rule a number of Chinese people was the Xia, who ruled from 2070 B.C. to 1600 B.C. in what is today Henan Province. The founder of this dynasty was Yǔ the Great, who was well-known in Chinese history for his efforts to overcome the devastating Huang He flooding. One famous saying was "But fo Yǔ, we would all be fishes." Under Yǔ's reign, he and other wealthy people lived in developed areas, and poorer people lived in rural areas. The people of this time made things of many shapes out of bronze.

The first dynasty to rule a number of Chinese people was the Xia, who ruled from 2070 B.C. to 1600 B.C. in what is today Henan Province. The founder of this dynasty was Yǔ the Great, who was well-known in Chinese history for his efforts to overcome the devastating Huang He flooding. One famous saying was "But fo Yǔ, we would all be fishes." Under Yǔ's reign, he and other wealthy people lived in developed areas, and poorer people lived in rural areas. The people of this time made things of many shapes out of bronze.

Yǔ decreed that his son, Qǐ, would succeed him as ruler, and this happened. Xia rulers so followed their fathers until 1600, when the Xia ruler Jiè found defeat at the Battle of Mingtiao, at the hands of Tang, from the kingdom of Shang. Tang found allies from within the Xia lands, in a number of people who had become dismayed at the harsh treatment of them by Jiè. Thus began the Shang Dynasty.

Shang Dynasty

The capital was in Yin (now Anyang), in the north. The people grew barley, millet, rice, and wheat and husbanded dogs, oxen, pigs, and sheep. They also looked after silk worms, which produced a prime revenue source. Those who carved did so using ivory and jade; sculptors used marble.

It was during this period (1600 B.C.–1046 B.C.) that Chinese people first began to write as we know it today. Archaeologists have found oracle bones with writing on them. These were mainly tortoise shells but were bones from other animals as well. A priest would write a question on the bone or shell and then heat it, interpreting the resulting cracks as a message from on high, from the gods or from their ancestors, whom many Chinese people also worshiped. The writing took the form of characters, of which people by this time already used 2000.

As before, one dynasty gave way to another because of oppression by the ruler. The last known king of the Shang Dynasty was Dé Xīn, who, after being defeated by Wu of Zhou at the Battle of Muye, ended his own life rather than submit in defeat.

Zhou Dynasty

It was from the Zhou Dynasty that the idea of the Mandate of Heaven found popular appeal. Chinese people had believed in a number of gods for many years. Among those many gods was the chief god, Shangti, who was the god of law, order, and justice. When things were going well, people believed that their ruler had the blessing of Shangti and the other gods, or the Mandate of Heaven. If the opposite were true, and things were not going well, then the people believed that their ruler had lost the Mandate of Heaven and could and should be overthrown. When rebelling against the Shang ruler, Wu, from the nearby Valley of the Wei River, claimed that the Shang ruler had lost the gods' favor.

It was from the Zhou Dynasty that the idea of the Mandate of Heaven found popular appeal. Chinese people had believed in a number of gods for many years. Among those many gods was the chief god, Shangti, who was the god of law, order, and justice. When things were going well, people believed that their ruler had the blessing of Shangti and the other gods, or the Mandate of Heaven. If the opposite were true, and things were not going well, then the people believed that their ruler had lost the Mandate of Heaven and could and should be overthrown. When rebelling against the Shang ruler, Wu, from the nearby Valley of the Wei River, claimed that the Shang ruler had lost the gods' favor.

During the Zhou Dynasty, people made great works of iron, built great weapons of war (among them an improved chariot), produced famous pieces of writing, and advanced their civilization significantly.

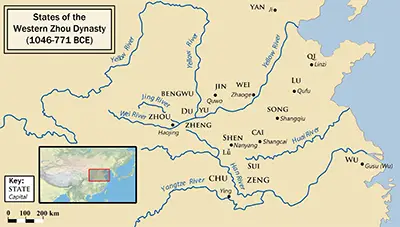

Hao was the first capital of the Zhou Dynasty, a very long-lasting series of rulers (1046 B.C.–256 B.C.). The kings ruled over a number of states that became increasingly independent. In 771 B.C., an angry mob killed the king, You. His grandson, Ping, founded the Eastern Zhou Dynasty, in what is now Luoyang but was then Luoyi. (It was called the Eastern Zhou Dynasty because of simple geography: Luoyi was east of Hao.)

Towns grew in size during this period, and many people made the transition from working on a farm to working as a merchant. Trade between towns flourished.

Some of China's most famous people lived during the Zhou period. Three of the most well-known were Confucius, Sun Tzu, and Lao-tzu.

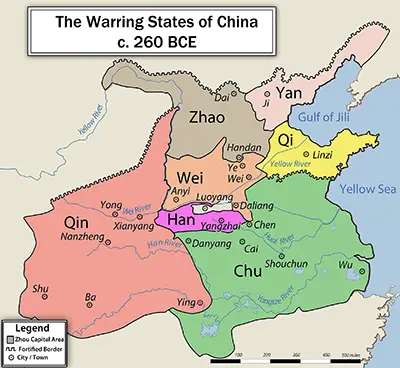

Historians classify the latter centuries of the Zhou Dynasty as the Spring and Autumn period and the Warring States period. During the former, the power of the king declined at the expense of the nobles, who exerted more and more influence over their subjects and eventually took to defying openly decrees from the court. Historians generally specify the division of the powerful state of Jin (into the states of Han, Wei, and Zhao) as the transition between the Spring and Autumn period and the Warring States period.

Perpetuating the internecine conflict during the Warring States period was Mo Ti, a pacifist philosopher who was also an accomplished engineer who tried to maintain the peace by providing each of the seven states with the same military knowledge, strategy, and equipment.

The Qin overcame this intended parity, defeating in turn the Han (230 B.C.), Zhao (229 B.C.), Yan (226 B.C.), Wei (225 B.C.), Chu (223 B.C.), and then Qi (221 B.C.). Ying Zheng, who became  King of Qin when he was just 13, put down a rebellion against his rule and then turned his warrior focus to his neighbors, conquering them all in turn and becoming Shi-huang-di, the first of many emperors of China.

King of Qin when he was just 13, put down a rebellion against his rule and then turned his warrior focus to his neighbors, conquering them all in turn and becoming Shi-huang-di, the first of many emperors of China.

|

|