Ancient Macedon

Part 1: Beginnings and Conquests Macedon was an ancient land to the north of Ancient Greece that grew in stature and capability and, for a time, absorbed its more well-known southern neighbors. The most famous leader of Macedon was Alexander the Great. The founder of Macedon is generally held to be Caranas, who did so in the 7th Century B.C. Caranas was the leader of the Mackednoi tribe, which gave the land its name. Another story is that this leader as named Perdiccas.

Another origin story has the god Makedon as the inspiration for the name of the land. In fact, the Greek writer Hesiod lists Makedon as being a member of the Greek pantheon. By and large, however, Macedonians considered themselves their own people, not Greeks, and the Greeks agreed. Macedonians generally kept to itself in terms of relations with the Greeks, except for the occasional goods trade. The first documented king of Macedon was Amyntas I, who ruled from 547 B.C. to 498 B.C. He was succeeded by his son, Alexander I, who competed in the Ancient Olympics, suggesting that he was of Greek descent. It was King Amyntas who agreed to place his kingdom under the overall rule of the Persian Empire, although Macedon did not become a satrap. Macedonians soldiers fought alongside those of Xerxes the Great in 480 B.C. After the Greek victory at Salamis, Xerxes pressed King Alexander I into service in an attempt to come to peace terms with Athens; he was unsuccessful. Succeeding Alexander in 454 was King Perdiccas II, who went to war a handful of times against Athens, in the time of its empire-building. Perdiccas initially allied with Sparta in the Peloponnesian War but changed sides during the war. Perdiccas found himself having to do business with Athens time and again during the three decades that the Archelaus found himself the victim of assassination in 399 B.C., and Macedon descended into anarchy punctuated by the ineffectual reign of no less than four monarchs. It was Amyntas III who restored stability to the kingdom, claiming the throne in 393 B.C. This king ruled for 23 years, facing down a couple of rebellions, to one of which he responded by fleeing the kingdom for a time. One of the aggressors in these rebellions were the Thessalians, and Alexander II, taking the throne in 370 B.C., set about invading that land as a measure of revenge.

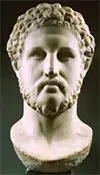

Macedon was at the center of various political intrigues and military struggles for the next 11 years, until the ascent to the throne of Philip II. Taking control of Macedon in 359 B.C., he set about conquering all of the southern Greek city-states and declared himself master of Greece. His next target was Persia, and he was in the middle of building up an invasion force for the purpose when he was assassinated. His son, Alexander the Great, fulfilled his father's dream of ruling Persia and a large amount of other lands as well.

What Philip started Alexander finished, with the development of a top-notch military, boasting the latest in equipment, tactics, and training. Philip it was who popularized the phalanx, the highly successful military formation whose executors appeared to be so many parts of a giant turtle, with each shield protecting the fighter next to the shield-wielder, who, in turn, was armed with a long pike that extended well behind the shield wall; the unit moved as one and proved incredibly difficult to defeat. Alexander combined the phalanx with missile-wielding troops–archers, javelin throwers, and stone slingers–and cavalry to form a devastatingly powerful and successful fighting force. At the same time, Philip was a deft diplomat, shoring up alliances through various turns of monetary compensation and political agreement. He married the Illyrian princess Audata in order to seal an alliance with that land. He married Philinna, a Thessalian noblewoman, to seal a deal with Thessaly; this union produced a son, Philip, who would succeed him as king. To ensure good relations with Arybbas, the King of Epirus, Philip II married Olympias; this union produced Alexander, who ruled for a time as King Alexander III. Philip and his troops moved on Greece, picking off the city-states one by one. Publicly, Philip insisted he was building a federation, one he called the Federal League of Corinth. Privately, however, he coveted Greece. This Federal League was announced and put into action in 338 B.C. This followed the major defeat of the Greeks at the Battle of Chaeronea. Of the major city-states, only Sparta was not involved. (In other words, Philip hadn't conquered Sparta yet.) Philip, however, decided to pursue bigger targets: He wanted a piece of the Persian Empire. Philip was a brilliant military commander and politician as well. He juggled the warring sentiments of the Greeks long enough to keep them ready for assimilation, then assembled them all under his banner into what was really a kingdom designed as a federation. He was a great tactician, and his plans for invading the Persian Empire were brilliantly executed#&8211;by his son. Philip was assassinated on the eve of his invasion of Persia. His son, Alexander, took over the reins of both army and kingdom and put the invasion plans in motion. He was 21. Next page > Alexander and Beyond > Page 1, 2 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White

war encompassed. Archelaus I, the successor to Perdiccas II, moved the capital from its original location, Aigai (also known as Vergina), to Pella. This new location gave the royal center access to the Aegean Sea via a nearby river. Archelaus also boosted the silver content in the royal currency and embarked on a period of cultural enrichment, in which he invited many famous Greek artists and writers to court; the famed playwright

war encompassed. Archelaus I, the successor to Perdiccas II, moved the capital from its original location, Aigai (also known as Vergina), to Pella. This new location gave the royal center access to the Aegean Sea via a nearby river. Archelaus also boosted the silver content in the royal currency and embarked on a period of cultural enrichment, in which he invited many famous Greek artists and writers to court; the famed playwright