The Whig Party in America enjoyed a few decades of uneven success then disappeared as a serious force in national politics, after sending four men to the White House.

The driving force behind the large-scale mobilization of the Whigs, first referred to as National Republicans, as a political party was opposition to the actions and policies of Democratic President Andrew Jackson, among them a series of internal improvements passed by Congress but vetoed by Jackson. Another point of contention was the Second Bank of the United States, which Jackson, suspicious of federal power, forced out of existence. Jackson, elected in 1828, ran for re-election in 1832 and his opponent was Clay, in the Whig Party's first nomination of a presidential candidate. The Whigs were still finding their feet politically, Jackson was still immensely popular, and the election wasn't close, with Jackson winning 219 electoral votes to Clay's 49. Clay returned to Congress and ramped up his opposition to Jackson and his policies. Clay and his fellow Whigs believed in a strong national economy and thought that the Bank of the United States was a bedrock of that national economy. Jackson didn't think so and stamped out repeated attempts to resuscitate the national bank. He also vetoed a series of tariffs championed by Whigs in Congress. When Jackson followed George Washington's precedent and bowed out after two terms in the White House, Martin van Buren took up the Democratic Party's mantle. The Whigs, trying to get clever, ran three candidates for President: Webster, William Henry Harrison of Ohio, and Hugh Lawson White of Tennessee. The hope was that each Whig candidate would win enough states in his home region to deny van Buren an overall victory, throwing the election into the House of Representatives, which the Whigs controlled. The strategy didn't work, however, as van Buren won a clear majority of the states and the presidency. The Whigs continued to gain influence and members throughout the last of the 1830s and ran a national campaign in 1840, with war hero Harrison as the presidential candidate and Virginian John Tyler as the vice-presidential candidate. The victory of Harrison in the presidential election must have seemed like a dream come true to the Whig Party, with its large membership in Congress as well. Harrison became the first Whig President but didn't live long enough to enjoy it, succumbing to illness and dying in office very early in his term. Tyler, a former Democrat, returned to form and vetoed the major Whig legislation. As a result, the Whigs tossed him out of the party. Tyler was still President, though, and remained so for the remainder of his four-year term.

The Whigs struck gold four years later, however, as Mexican-American War hero Zachary Taylor won a national campaign with Millard Fillmore as his vice-presidential candidate. Like Harrison before him, Taylor died before his term was out. Fillmore became President. Fillmore became notable for approving of the Compromise of 1850">Compromise of 1850 (created by Clay), yet another slavery stopgap; this one, however, Taylor would have vetoed. Even though Clay and Taylor won states up and down the country, such national support was rare. Even though the Whigs found common ground with some of Clay's and Webster's ideas in Congress, they felt first affinity to their regional issues. Nowhere was this more evident than on the issue of slavery. Like the rest of the country, the slavery issue split the Whig Party along lines North and South. Fillmore's support of the Compromise of 1850, and its introduction of the Fugitive Slave Law, lost him considerable support in his own political party, so much so that he wasn't even nominated to run for re-election. In 1852, after the deaths of both Clay and Webster, the Whigs chose Mexican-American War hero Winfield Scott as their nominee, hoping to repeat Taylor's success. The result was not the same, as Democrat Franklin Pierce won a resounding victory. Scott was the last serious Whig Party presidential candidate. Sundered by the slavery issue and repeated factional struggles (including a wide split over the Kansas-Nebraska Act and the issue of "popular sovereignty"), the Whig Party disintegrated in multiple directions. Many Whigs, including Illinois' Abraham Lincoln, joined the newly formed Republican Party. Other Whigs joined another new political party, the Know-Nothings. These two new parties both ran candidates in the 1856 presidential election: John C. Fremont of California was the Republican Party's first standard-bearer, and former President Millard Fillmore ran under the Know-Nothing banner. The Democrats' hold on the White House continued, however, as James Buchanan swept to victory. The Whig legacy extended into the next legacy as well, as former Whig Abraham Lincoln ran as a Republican and a great many other former Whigs formed a brand new party, the Constitutional Union Party. Its presidential candidate, John Bell, did rather well in the election, outdistancing his more well-known Northern Democratic opponent Stephen A. Douglas. The Whigs also enjoyed strong support among the nation's newspapers, first and foremost the New York Tribune's Horace Greeley, himself a presidential candidate in 1872, long after the demise of the Whigs. Another well-known Whig was Horace Mann, leader of the drive to implement universal public education. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White

Kentucky's

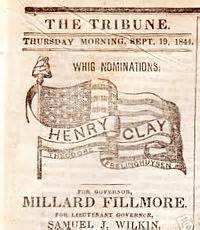

Kentucky's  Clay came as close to the presidency as he was ever going to get in the next election, scoring 105 electoral votes across a wide expanse of states. It was one of the closest popular vote tallies in history. It wasn't enough, however, to give the Clay the White House because Democrat

Clay came as close to the presidency as he was ever going to get in the next election, scoring 105 electoral votes across a wide expanse of states. It was one of the closest popular vote tallies in history. It wasn't enough, however, to give the Clay the White House because Democrat