|

|

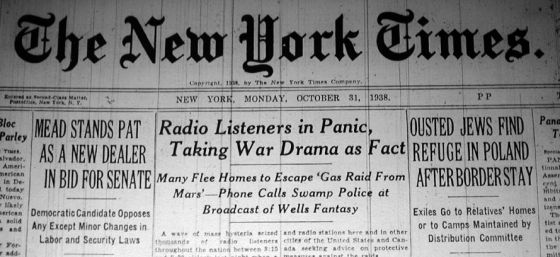

Panic in the Streets: The War of the Worlds on the Radio

|

|

|

|

Share This Page

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Follow This Site

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Part 2: Resolution and Relief

What many of these people missed or forgot was that none of what they were hearing was actually happening. The very first words of the broadcast were from the novel itself. At various times during the broadcast, announcements reminded listeners that they were listening to a cleverly conceived and presented work of fiction. What many of these people missed or forgot was that none of what they were hearing was actually happening. The very first words of the broadcast were from the novel itself. At various times during the broadcast, announcements reminded listeners that they were listening to a cleverly conceived and presented work of fiction.

In the early part of the broadcast, which described the landing of a mysterious meteor in the New Jersey countryside, curious listeners, including scientists from Princeton, scoured the landscape looking for the meteor. These people found nothing but one another.

Many people missed the beginning or the reminders and heard only the "terrors." Many phone calls later, the streets were full of people running or driving away, determined to escape the city before it was overrun by aliens from another planet.

Martian war machines were definitely not wading across the Hudson River. No news reporter witnessed all those amazing events before succumbing to poison gas. Princeton professor Richard Pierson was a figment of the Mercury Theatre troupe's imagination — not to mention that it was actually Orson Welles playing the part of Pierson.

The events described were horrific. Death rays annihilated all in their path. The death toll was at least 1,500. Fires burned all about the countryside. The events described were horrific. Death rays annihilated all in their path. The death toll was at least 1,500. Fires burned all about the countryside.

The number of inquiries at newspapers and police stations was so many that the Associated Press issued a statement clarifying that the radio broadcast was indeed "a studio dramatization." Similar instructions were sent to all police stationhouses and patrol cars, so that officers could inform fleeing New Yorkers that they had no reason to be afraid (even though some people insisted that they could see flames from fires that were't there).

It wasn't just in New York and New Jersey that panic reigned, however. The broadcast was a national one; estimates at the time were that 6 million people heard it. People in other parts of the country were hearing the same broadcast, and many were just as worried about what was happening to their family, friends, or fellow Americans. Reports came in of people booking flights to New York to check on family members, of doctors and nurses calling New York and New Jersey hospitals with offers of helping hands, and of theater performances and church services being dismissed so the attendees could go home to pray.

The broadcast lasted just an hour, at the end of which Welles came on and introduced himself:

"This is Orson Welles, ladies and gentlemen, out of character to assure you that "The War of The Worlds" has no further significance than as the holiday offering it was intended to be. The Mercury Theatre's own radio version of dressing up in a sheet and jumping out of a bush and saying Boo!"

Many people were not amused, although they were relieved. Welles became even more famous than he was, once people had had some time to laugh it all off.

First page > Hook, Line and Sinker > Page 1, 2

|

|