The Republic of Texas

It was known to the Spanish-speaking citizens of Mexico as Coahuila y Tejas. To English-speaking citizens living in the same country, it was Mexican Texas. In 1836, it became the Republic of Texas.

Several Spanish missionaries had been through what is now Texas in the 16th Century and the 17th Century. Spain had nominally claimed a large part of what is now the western United States after the arrival of Christopher Columbus in 1492 and the signing of the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494 but had maintained a slight military presence in the vast territory because of a lack of European competition. France had claimed part of what is now Texas as part of the Louisiana Territory but had ceded some of that Spain in 1762, during the French and Indian War. The ascent of Napoleon to power in France at the turn of the 19th Century resulted in French occupation of Spain and French assumption of many Spanish claims, including what had been called Spanish Louisiana. Napoleon then sold the entire Louisiana Territory to the United States in 1803, in the Louisiana Purchase. As a result, the status of what is now Texas was unclear. The Adams-Onís Treaty of 1819 provided clarity to the situation, along with transferring ownership of Spanish Florida from Spain to the U.S.

By that time, various parts of what was then called New Spain sought independence from Spain. Primary among these was Mexico, which gained its independence in 1821. Many Americans fought with Mexicans against Spain during this struggle. During this time, a number of Americans created a nascent Republic of Texas. After a victory of Spanish at the Battle of Rosillo Creek in 1813, members of the Republican Army of the North announced the creation of a Republic of Texas, complete with a constitution and a president, Bernard Gutiérrez de Lara. Not taking too kindly to the insurrection, Spain sent a determined group of soldiers to crush the revolt, and they did so on August 18, 1813, at the Battle of Medina. As a result of the Treaty of Córdoba in 1821, Mexico was a free country. Originally a constitutional monarchy, it became an empire. Before that, however, Stephen F. Austin led a group of settlers known as the Old Three Hundred into Mexico, establishing Mexican Texas. Very early on, they referred to themselves as Texians. Conflicts over whether to allow slavery in the area by subsequent settlers, known as Empresarios, led to the cessation of American immigration by President Anastasio Bustamante. Empresarios responded by gathering at the Convention of 1832, a series of political discussions that resulted in a series of resolutions sent to the Mexican government. Two years later, a new Mexican president, Antonio LŖpez de Santa Anna, declared the Mexican constitution void and began a series of actions that resulted in his becoming the Emperor of Mexico. Suspicious Americans took up arms (in the form of the Texian Army) in response to a heightened presence in Mexican Texas by the Mexican Army, and the result was an armed conflict, which began on Oct. 2, 1835, at the Battle of Gonzales. Another political gathering, known as the Consultation, followed, and the move toward independence gathered steam.

A third and more intense gathering, the Convention of 1836, began on March 1, 1836. The following day came into being the Republic of Texas, an entity independent from Mexico. Sam Houston was the first President of the Republic of Texas, and the Burnet Flag (after interim President David Burnet) was its first flag. To start with, the Republic had temporary capitals, which numbered five in all: Washington-on-the-Brazos, Harrisburg, Galveston, Velasco, and Columbia. In 1837, Houston moved the capital to the newly created town named after him. The constitution set out a two-house Congress–a House whose members would serve one-year terms and a Senate whose members would serve three-year terms–and a president, who would serve a three-year term and could not run for re-election. The President and members of Congress were to be elected by the people of the republic. Also provided for was a Supreme Court, with five justices, including a chief justice, all of whom were to serve four-year terms. Members of Congress were to elect the justice. Slavery was legal, but the foreign slave trade was not. Free African-Americans had to have permission from Congress in order to live in Texas. Just days after the declaration of independence, the Mexican Army killed all of the defenders at San Antonio's Alamo and then, three weeks later, executed 350 Texan prisoners at Goliad. Fortunes changed precipitously in April, when Houston took advantage of a rare mistake by Mexican General Antonio López de Santa Anna and launched a surprise attack. The Battle of San Jacinto, on April 21, resulted in a rout so complete that Santa Anna was himself captured. The Texian Army had attacked with a force half the size of Mexico's and won a stunning victory. Houston didn't escape unscathed: He sustained a severe wound and had his horse shot out from under him. The two leaders signed a treaty, ending the war over Texas.

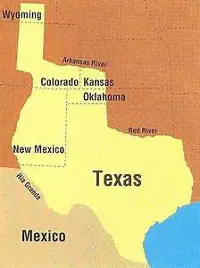

Succeeding Houston as President of Texas was Mirabeau B. Lamar, who moved the capital again, this time to Austin, in 1839; also in that year debuted the new flag, the Lone Star Flag. Lamar and many others in Texas wanted to expel Native Americans and to expand the borders of Texas westward. Houston and others did not want an expulsion of Native Americans and did want Texas to become part of the United States. Lamar's election as president in 1838 brought about major conflict with nearby Native Americans, particularly the Comanche, who launched a number of raids throughout the Republic. Houston's return to the presidency in 1841 brought with it peace between Texians and Native Americans. In 1842, conflict with Mexico began again, with an invasion of 500 soldiers led by Ráfael Vásquez who briefly occupied San Antonio. They went back to Mexico after a few days. At the end of 1842, fearing a Mexican takeover of Austin, a forced led by Texas President Sam Houston went to Austin with the intent of transferring the seat of government and all of its records to the town of Houston. Sam Houston's men found resistance from the residents of Austin, who eventually relented. This confrontation came to be known as the bloodless Archives War. Such occurrences were rare in the next few years, as the drumbeat for annexation accelerated. It didn't hurt that other parts of Mexico had risen up in revolt against the emperor. Anson Jones was elected President of Texas in 1844. It was he who presided over the republic's joining the United States. On Feb. 28, 1845, the U.S. Congress passed a bill allowing for the annexation of Texas on December 29. President John Tyler signed the bill into law on March 1. Texians themselves approved the bill with a large majority on October 13, and Texas became a state on December 29. That officially marked the end of the Republic of Texas. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White