The Election of the President Throughout U.S. History

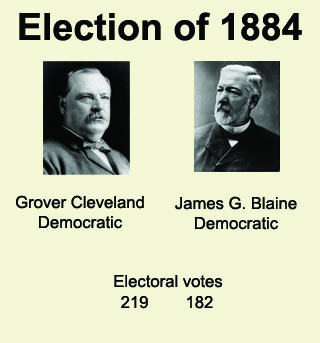

Part 4: 1872 to 1896 The Election of 1872 One of the main issues in the campaign, other than aforementioned concerns over Reconstruction and federal troops, was allegations of corruption in Grant's government. Grant proved popular indeed, winning re-election by a large margin, besting Greeley by a large margin in the popular vote and an overwhelming margin in the electoral count. Grant's electoral total was 286. Greeley's ticket carried six states and would have received 66 electoral votes but for the fact that Greeley died before the electoral votes were cast. As a result, his votes were divided among four other men. This election was also the first to have a female presidential candidate: Victoria Woodhull, representing the Equal Rights Party. Her running mate was Frederick Douglass. The Election of 1876 The Republicans, meanwhile, campaign on, among other things, the overall issue of the Civil War, a strategy that Democrats decried as "waving the bloody shirt." Coming into the Union just before the election was Colorado, the latest addition from the Mexican Cession. The results of the election of 1876 made it, up to that time, the most controversial in history. When the votes were counted, Tilden had won the popular vote, 4.2 million to 4 million. This should have meant that Tilden was President. Even in previous elections in which the popular vote was close, the winner of the popular vote total was the winner in the Electoral College. Of the votes counted, Tilden had won 184 electoral votes, to 165 for Hayes. That wasn't enough because the total was 369 and the winner needed 185. A total of 20 electoral votes had not been cast because of election disputes in Florida, Louisiana, Oregon, and South Carolina. After some serious back-door wrangling, representatives in those states cast all of their electoral votes for Hayes, giving him the needed 185. This came to be known as the Compromise of 1877 because it resulted in the end of Reconstruction and the withdrawal of federal troops from the South. The Democratic Party had given up a short-term gain, the presidency, in exchange for a long-term gain. Tilden supporters were especially stung by Hayes' winning in Colorado, statehood for which they had pushed through in hopes of winning. The Election of 1880 Running for the Democratic Party was Civil War general Winfield Scott Hancock. (Tilden, despite "winning" last time around, did not run again.) One of the main issues of the election campaign was whether to impose higher tariffs on other countries. Republicans said yes, and Democrats said no. Garfield won the election, barely, by less than 2,000 popular votes. The electoral vote tally was a bit of a wider spread, 214-155. All of the Southern states, with the addition of California and Nevada, went for Hancock. The Northeast and the Midwest went for Garfield, whose running mate was Chester A. Arthur. The Election of 1884 In his stead, the Republican Party nominated James G. Blaine, who had a long list of political credentials, including representing Maine in the House and Senate and serving as Secretary of State under Garfield. (Blaine, like most of the rest of the Cabinet, resigned after Garfield was shot.) New York Gov. Grover Cleveland was the Democratic nominee. In the election campaign, both parties tried to paint the other party's candidate as corrupt or of questionable character. The election was one of the closest electoral contests in history, with Cleveland just managing to win his home state of New York and, with its 36 electoral votes, the election 219-182. The Election of 1888 In 1888, Cleveland ran for re-election (and was supported by his party, the first time that had happened since 1836) with this as a major campaign issue. His opponent was former Indiana Senator Benjamin Harrison, a grandson of former President William Henry Harrison. (Blaine, the 1884 standard-bearer, chose not to run again.) On election day, Cleveland and the Democrats garnered more popular votes than Harrison and the Republicans, but it was the Electoral College that determined the winner, as always, and Harrison, by less than 1 percent, managed to win Cleveland's home state, New York, and with it, the election. The final popular vote tally had Harrison ahead by just more than 90,000 votes, out of nearly 10.5 million votes cast. The final electoral tally was 233-168, to Harrison. As First Lady Frances Cleveland left the White House, she assured the staff that she and her husband would come back in four years' time. The Election of 1892 The Democrats believed in more free-market approaches. As it turned out in this election, so did the majority of Americans. Cleveland easily won re-election (although not a consecutive one), outdistancing Harrison clearly in both popular and electoral votes. Cleveland claimed 277 of the 344 electoral votes on offer, to Harrison's 145. Third-party candidate James B. Weaver won four states and, with them, 22 electoral votes. The continental map of the U.S. was nearly complete at this time, with the Union admitting Idaho, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Washington, and Wyoming. The Election of 1896 The election pitted Bryan, with his support made up of factory workers and farmers and small-business owners, against Republican Ohio Gov. William McKinley, with his support made up of banks, merchants, and factor owners. The election captivated the interest of most of the country, and the result was one of the highest turnouts by percentage in the country's history. When the dust had settled, McKinley had carried 23 of the 45 states. The states that McKinley carried provided the difference. His electoral vote tally was 271, to Bryan's 176. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White

Grant enjoyed success throughout the country as President and was nominated again in 1872. A bloc of Republicans, however, wanted an end to Reconstruction and a withdrawal of federal troops from the South. Breaking away and calling themselves the Liberal Republicans, they nominated newspaper editor

Grant enjoyed success throughout the country as President and was nominated again in 1872. A bloc of Republicans, however, wanted an end to Reconstruction and a withdrawal of federal troops from the South. Breaking away and calling themselves the Liberal Republicans, they nominated newspaper editor  Tilden was very popular in the Northeast and across the country. One of his main claims to fame was the successful prosecution of "Boss" William Tweed. Tilden and the Democrats campaigned on a promise of governmental reform, which would have sounded like relief to many who had grown weary of Grant and his government's scandal-ridden reputation.

Tilden was very popular in the Northeast and across the country. One of his main claims to fame was the successful prosecution of "Boss" William Tweed. Tilden and the Democrats campaigned on a promise of governmental reform, which would have sounded like relief to many who had grown weary of Grant and his government's scandal-ridden reputation.  Hayes had promised not to run for re-election, and he kept that promise. The Republican candidate in the election of 1880 was Ohio's

Hayes had promised not to run for re-election, and he kept that promise. The Republican candidate in the election of 1880 was Ohio's  Garfield's presidency lasted just 200 days. He was assassinated in September of 1881, and Arthur became President. He served out the remainder of Garfield's term and, because of poor health, decided against running for re-election.

Garfield's presidency lasted just 200 days. He was assassinated in September of 1881, and Arthur became President. He served out the remainder of Garfield's term and, because of poor health, decided against running for re-election.  The Industrial Revolution was catching on in the United States in the latter half of the 19th Century. As before, President Cleveland and the Democrats thought that high tariffs were unfair to consumers.

The Industrial Revolution was catching on in the United States in the latter half of the 19th Century. As before, President Cleveland and the Democrats thought that high tariffs were unfair to consumers.  When Harrison ran for re-election in 1892, his opponent again was Cleveland. This time, tariffs were even more on the minds of politicians and voters. Of particular interest was the McKinley Tariff, a protectionist tariff that raised the average duty on imports from 38 percent to 49.5 percent.

When Harrison ran for re-election in 1892, his opponent again was Cleveland. This time, tariffs were even more on the minds of politicians and voters. Of particular interest was the McKinley Tariff, a protectionist tariff that raised the average duty on imports from 38 percent to 49.5 percent.  Cleveland's second term was plagued by economic unrest, with a full-blown depression setting in following the Panic of 1893. Cleveland was not chosen to run again, with the Democrats deciding instead on William Jennings Bryan, a former Nebraska Representative who was known for his superior oratory skills. His speech at the 1896 Democratic National Convention is one of the most famous in American history; in this "Cross of Gold" speech, he pleaded with the big business interests of America to reform the monetary system and end reliance on the gold standard.

Cleveland's second term was plagued by economic unrest, with a full-blown depression setting in following the Panic of 1893. Cleveland was not chosen to run again, with the Democrats deciding instead on William Jennings Bryan, a former Nebraska Representative who was known for his superior oratory skills. His speech at the 1896 Democratic National Convention is one of the most famous in American history; in this "Cross of Gold" speech, he pleaded with the big business interests of America to reform the monetary system and end reliance on the gold standard.