One of the most famous journalists of the 19th Century was Nellie Bly, and that wasn't even her real name.

She was born Elizabeth Cochrane on May 5, 1864, to Michael and Mary Jane Cochrane in the town of Cochran's Mills, near Pittsburgh, Penn. Her father had worked at the local mill, then bought it and a large amount of land. He expanded his business holdings to be a merchant, postmaster, and judge and named the settlement after himself. Mary Jane and Michael had four children in addition to Elizabeth; Michael and his first wife, Catherine, had 10 children.

Elizabeth wore pink often as a child and was called "Pinky." She later discouraged people from calling her that and added an "e" to her last name, becoming Elizabeth Cochrane. She went away to boarding school with hopes of being a teacher but didn't finish because her father's death left the family with little money. She and her mother ran a boarding house to try to make ends meet.

Elizabeth moved with her mother to Pittsburgh in 1880. The then-16-year-old Elizabeth became incensed after reading a sexist newspaper column titled "What Girls Are Good For" and wrote a letter to the editor, signing herself "Lonely Orphan Girl." The paper was the Pittsburgh Dispatch; its editor, George Madden, was impressed with the passion of the writer of that letter and took out an ad in his own paper, imploring the writer to reveal her identity. Elizabeth went to meet the editor, and he offered her a one-time job, a rebuttal to "What Girls Are Good For," writing under the byline "Lonely Orphan Girl." The result was an article headlined "The Girl Puzzle," and Madden was so impressed that he offered Elizabeth a full-time job as a reporter.

Elizabeth moved with her mother to Pittsburgh in 1880. The then-16-year-old Elizabeth became incensed after reading a sexist newspaper column titled "What Girls Are Good For" and wrote a letter to the editor, signing herself "Lonely Orphan Girl." The paper was the Pittsburgh Dispatch; its editor, George Madden, was impressed with the passion of the writer of that letter and took out an ad in his own paper, imploring the writer to reveal her identity. Elizabeth went to meet the editor, and he offered her a one-time job, a rebuttal to "What Girls Are Good For," writing under the byline "Lonely Orphan Girl." The result was an article headlined "The Girl Puzzle," and Madden was so impressed that he offered Elizabeth a full-time job as a reporter.

For reasons that are still disputed, she chose a pseudonym, or pen name. After discussing it with Madden, she settled on a version of Nelly Bly, the title character in a popular song by the popular composer Stephen Foster. Somewhere along the way, Nelly got changed to Nellie.

Nellie Bly began her career at the Pittsburgh Dispatch writing investigative articles. Foreshadowing one of her most famous accomplishments, she posed as a sweatshop worker in order to write a firsthand account of the harsh conditions endured by female factory workers. She wrote further investigative articles on similar topics, and local businesses expressed their concern to the newspaper's top brass. Bly found herself reassigned to the society pages of the newspaper.

At 21, she convinced her bosses to finance a trip to Mexico, where she reported on the lives and customs of the people there. She also wrote articles critical of the Mexican government and found herself threatened with imprisonment; she came home and eventually found herself again assigned to the "women's pages." In 1887, she moved to New York City, to try to get a job at one of that city's many newspapers.

The New York World, owned by famed publisher Joseph Pulitzer, eventually took her on, and her first assignment turned out to be an expose on an asylum.

Bly went undercover, feigning insanity, first at a boardinghouse and then before a bevy of doctors, all of whom declared her "crazy," "demented," and "insane." She had practiced certain facial expressions, mannerisms, and physical behaviors repeatedly, and the combination served to convince enough people of her mental fragility that she was admitted as a patient at the Women's Lunatic Asylum on Blackwell's Island.

Bly went undercover, feigning insanity, first at a boardinghouse and then before a bevy of doctors, all of whom declared her "crazy," "demented," and "insane." She had practiced certain facial expressions, mannerisms, and physical behaviors repeatedly, and the combination served to convince enough people of her mental fragility that she was admitted as a patient at the Women's Lunatic Asylum on Blackwell's Island.

She feigned amnesia and paranoia, and many people looked at pictures of her and said she was attractive. She became known in reports in the New York press as the "pretty crazy girl."

While inside the asylum walls, Bly saw firsthand the horrid conditions endured by the inmates. The food was spoiled, the water undrinkable. Patients deemed dangerous were tied together with ropes. All patients were made to sit on uncomfortable benches for hours on end, watching the ever-present rats stalk their legs and leavings. Baths were by way of buckets of frigid water poured over their heads. Clothing was minimal, and linens were soiled.

Bly was particularly appalled by the behavior of the nurses, who verbally and physically abused the inmates.

By all accounts, Bly dropped her insane act when she was admitted, yet the doctors who continued to examine her continued to declare her insane. She also talked enough with a few other inmates to conclude that they, too, had no business being locked up in an asylum.

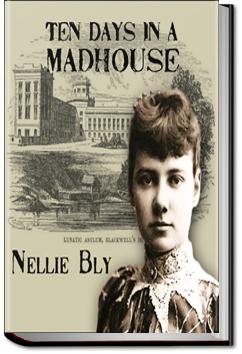

The newspaper planned to arrange her release after 10 days. Her cover was nearly blown by a fellow reporter from another newspaper, who arrived to interview the "pretty crazy girl." She dropped her cover and implored him not to reveal her identity. He did not, and the World secured her release. She then set to work publishing her experiences, which took the form of a book, Ten Days in a Mad House. The book brought her fame and resulted in reforms in the medical profession. A grand jury investigation into the asylum's practices resulted in a tour led by Bly herself; by that time, hospital officials had removed much of the evidence. Still, Bly's efforts to expose injustice and raise awareness had been successful.

The newspaper planned to arrange her release after 10 days. Her cover was nearly blown by a fellow reporter from another newspaper, who arrived to interview the "pretty crazy girl." She dropped her cover and implored him not to reveal her identity. He did not, and the World secured her release. She then set to work publishing her experiences, which took the form of a book, Ten Days in a Mad House. The book brought her fame and resulted in reforms in the medical profession. A grand jury investigation into the asylum's practices resulted in a tour led by Bly herself; by that time, hospital officials had removed much of the evidence. Still, Bly's efforts to expose injustice and raise awareness had been successful.

That was in 1887. The very next year, Bly suggested another epic story: She wanted to travel around the world.

The protagonist of a recently published very famous book, Around the World in Eight Days, was Phileas Fogg. The book was written by the equally famous Jules Verne in 1873. Bly suggested to her editors that she could complete the journey in fewer than 80 days, and they agreed to finance her attempt.

Preparations took a bit of doing, during which time she continued to write, publishing exposes on jails and factories. Then, it was time to beat Phileas Fogg.

Bly set out on her circumnavigation from Hoboken, N.J., on November 14, 1889. It was a journey of 24,899 miles. She took very little with her: a few changes of clothes, some toiletries, and a small travel bag. Her money was with her at all times, secured in a bag tied around her neck.

Bly set out on her circumnavigation from Hoboken, N.J., on November 14, 1889. It was a journey of 24,899 miles. She took very little with her: a few changes of clothes, some toiletries, and a small travel bag. Her money was with her at all times, secured in a bag tied around her neck.

She made her way across Europe and Asia. She traveled by ship, by rail, in a rickshaw, in a sampan, and on the back of a burro.

When she arrived back in the United States, in San Francisco, she was two days behind schedule. New York World owner Pulitzer chartered a private train to bring her the rest of the way home, and she returned well within her target, completing the journey in 72 days, 6 hours, 11 minutes, 14 seconds. She finished on Jan. 25, 1890. While she was traveling, the World organized a contest, urging readers to predict exactly when she would return.

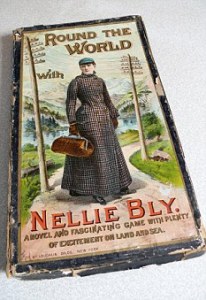

As the result of her asylum expose and her round-the-world journey, she became one of the most recognized people in America. An 1890 board game, Round the World with Nellie Bly, was one of many promotional materials popular with the public. She also went on a lecture tour to relate her adventures and to promote her new publication, Nellie Bly's Book: Around the World in Seventy-two Days.

As the result of her asylum expose and her round-the-world journey, she became one of the most recognized people in America. An 1890 board game, Round the World with Nellie Bly, was one of many promotional materials popular with the public. She also went on a lecture tour to relate her adventures and to promote her new publication, Nellie Bly's Book: Around the World in Seventy-two Days.

She returned to work at the World in 1893. Her writing regularly appeared on the front page. She continued to write hard-hitting pieces, on topics such as police corruption and the violent and long-lasting Pullman labor strike. She also interviewed famous people, including suffragette leader Susan B. Anthony.

Bly married Robert Seaman, a very rich businessman, in 1895. She was 31; he was 73. She left newspapering and went to work at his business, the Iron Clad Manufacturing Company. He died in 1904, and she ran the company from then on.

Iron Clad made steel boilers and milk cans. Bly, now Elizabeth Cochrane Seaman, improved on two of the company's products, receiving patents for a certain kind of milk can and for a stacking garbage can.

The company fell on hard times, and she went back to reporting, this time in Europe, issuing dispatches from the Eastern Front in World War I to the New York Journal. She returned to New York in 1919 and continued to write for the Journal.

Bly died in New York on Jan. 27, 1922. She was 57.

She has been the inspiration for a great many female reporters and the subject of a Broadway musical, many TV shows, and many more books and magazine articles.