The Lincoln-Douglas Debates were a series of speeches given by Illinois Senate candidates Stephen A. Douglas and Abraham Lincoln during the 1858 election campaign. They numbered seven in all and played no small part in making Lincoln's a household name.

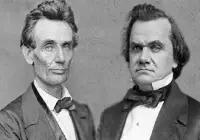

The two protagonists were Douglas (right, right), representing the Democratic Party, and Lincoln (right, left), representing the Republican Party. Douglas had represented Illinois' 5th District in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1843 to 1847. He was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1846 and had been re-elected in 1852. Lincoln, by contrast, had served one term in the U.S. House, from 1846 to 1848, before returning to his law practice. He had campaigned for various Whig and Republican candidates in previous elections, though, and was known to Illinois voters. These were the first debates between candidates for a Senate seat in U.S. history. Douglas had debated Lincoln earlier, during the presidential election campaign of 1840, when Douglas was supporting Martin van Buren and Lincoln was supporting the Whig Party, which was fielding a number of candidates. In fact, they had debated dozens of times. This time, the stakes were much higher. Lincoln had given his famous "House Divided" speech in Springfield on June 16, 1858. Among other things, he said, "A House divided against itself cannot stand," referring to the slavery split still consuming the nation. Douglas was already one of the most famous lawmakers in the country, having twice been a strong contender for the Democratic Party nomination for president and the architect of some famous (or infamous) laws of late. The two candidates agreed to have a debate in each of the state's nine congressional districts. They had seven debates in all because they had already spoken in Chicago and Springfield and had ticked off those districts. The other debates were these:

The candidates did not engage in any sort of point-counterpoint; rather, they spoke for long periods of time. The two-hour debate format called for one candidate to open with a 60-minute presentation and close with a 30-minute wrapup, in between which the other candidate spoke for 90 minutes. Douglas, as the incumbent, spoke first in four of the seven debates. The main issue of the debates was slavery. Douglas was by this point knee-deep in a political fracas regarding his championing of the doctrine of Popular Sovereignty, the idea that people in a territory or state could decide for themselves whether they would permit slavery within their borders. This idea was implicit in the Compromise of 1850 and explicit in the Kansas-Nebraska Act, both congressional laws authored and engineered by Douglas. It was the Kansas-Nebraska Act that had, in effect, contravened the Missouri Compromise, the 1820 law that had effectively drawn a North-South line across the country and stated that Congress alone had the power to determine whether a state would allow slavery. As the Senate campaign began, Douglas was also in the throes of a national debate over the constitution for the Kansas Territory, the residents of which had applied for statehood. The neighboring state of Missouri had a constitution that allowed slavery, and many Missouri residents thought nothing of crossing the border into Kansas in order to intimidate those who opposed slavery or just didn't care one way or the other. Violence became something of the norm, leading to the territory's being referred to as "Bleeding Kansas". A number of slavery proponents had manipulated things to the extent that they had submitted a pro-slavery constitution to Congress. The Lecompton Constitution was the product of a pro-slavery convention in the town of that name, and President James Buchanan had urged Congress to accept that document as the blueprint of the new state of Kansas. The Senate agreed, but the House did not. Douglas had not supported the Lecompton Constitution, and this angered slaveowners. The two candidates traded charges regarding various positions regarding slavery, its abolition, and Popular Sovereignty. Each candidate tried to depict the other as endorsing extreme positions. Each candidate tried to hedge his bets with regard to keeping abolitionists and slaveowners onside. Lincoln did his share of trying to thread the needle. He personally abhorred slavery but was careful not to appear as too much of an abolitionist or too much of an advocate of racial equality, for fear of alienating people who would otherwise vote for him. A great many white people believed that slavery should be eradicated but did not believe that African-Americans and European-Americans were equal. Lincoln also went out of his way to stress that he would support no position or plan that would result in war. Douglas certainly believed that African-Americans were inferior to European-Americans and said so on many an occasion. An opponent of slavery as well, he struggled mightily to convince people that his championing of Popular Sovereignty did not mean that he would vote to allow slavery in places where it was frowned on or outlawed.

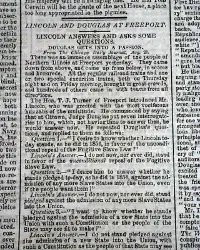

Another way in which Douglas tried to have it both ways was in response to Lincoln's challenge that he reconcile the doctrine of Popular Sovereignty with the recent Supreme Court decision Dred Scott v. Sanford, in which the Court had held that slaves had no rights under the Constitution and never would because they were and would forever be property. Douglas took this issue head-on, in the second debate. In what came to be known as the Freeport Doctrine, Douglas reasserted his idea that residents of a state or territory could decide for themselves whether they would allow slavery, no matter what the Supreme Court had said. Lincoln also argued that slavery was morally wrong, a position with which Douglas steadfastly refused to agree, and that the federal government was the only governing body that had the power to abolish slavery; however, Lincoln also made it clear that he would take no action against locales in which slavery was already countenanced and protected by law. At that time, membership in the U.S. Senate was determined not by popular vote but by a vote of each state's senators. At the time, Illinois Democrats held 40 seats in the state house and 14 seats in the state senate and Illinois Republicans held 35 seats in the state house and 11 seats in the state senate. The vote for Senator was 54 for Douglas and 46 for Lincoln. Douglas was re-elected. The debates had generated a large amount of news coverage and discussion, not only in Illinois but also elsewhere in the country. Many newspapers printed verbatim some of the speeches given by the candidates. As well, people came from neighboring states in large numbers to personally witness the debates. As a result, Lincoln gained nationwide exposure. He later published a full transcript of the debates. Douglas's threading-the-needle arguments during the debates and his continuing to champion Popular Sovereignty cost him support in both the North and the South, support he could ill afford to lose. When the two candidates met again as opponents, in the presidential Election of 1860, Douglas's words and positions came back to haunt him. The North-South split of the Democratic Party didn't help, either. Nonetheless, Lincoln was elected President. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White

Aug. 21: Ottawa

Aug. 21: Ottawa