Indentured Servants

It wasn't long after the first Virginia Company settlers hunkered down in the Jamestown settlement that indentured servants followed them across the Atlantic Ocean in search of work and opportunity. Many of these newly arrived people entered into contractual agreements with planters and landowners. As a result, many of these workers were termed indentured servants.

Tobacco was one of the main crops in Virginia and a few other colonies. Farther south, the crops were cotton, indigo, and rice. Landowners and plantation owners found these crops in abundance in many areas and needed large numbers of workers to till the land and harvest the crops. By contrast, in New England, many indentured servants entered into contracts with whalers and served out their time aboard whaling ships. (Many whaling indentured servants were, in fact, Native Americans.) In all parts of the 13 Colonies, the need of indentured servants extended to work of a domestic nature, including household management.

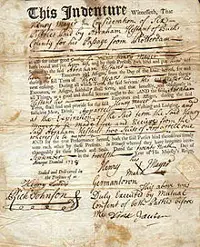

A typical indentured servitude arrangement would involve the master, or boss, paying the transatlantic fare of the new worker, who would then sign a contract agreeing to work for a period of time in the fields or on the land of the master. A typical arrangement involved a service agreement of five years, during which time the master would supply food and accommodation but, usually, not money. At the end of this period, both parties were free not to extend the contract. If the servant chose to leave, then the master usually sent him or her away with an already negotiated set of materials such as money, clothes, food, tools, or even a title to some land. These were called freedom dues. In theory, this arrangement seemed to benefit both parties somewhat equally: the master got a worker for a number of years, toiling away on land or in fields, and could avoid paying money for that work, instead paying only room and board; and the servant got that room and board paid for while also building up a set of skills to help him or her in the next job.

In practice, however, the master usually got the better end of the deal. For a start, historical figures show that in America, only 40 percent of indentured servants lived through their entire time of service. The work that they did was backbreaking and often dangerous. As well, some contracts were for much more than five years. For example, female indentured servants who became pregnant found their contracts lengthened to compensate for the time lost in the last few weeks before giving birth and the first few weeks afterward. The colonies in America had a handful of laws that protected indentured servants to a degree. However, masters were usually free to discipline their indentured servants how they saw fit. Servants also needed their master's permission in order to marry. Many indentured servants were African-American. As such, they were often subject to different outcomes. An indentured servant who ran away and was captured and brought back to his or her master could be punished while also having the servitude contract extended. In one well-known instance in the Virginia Colony in 1640, three runaway indentured servants were captured and were taken to court by their master. The General Court of Virginia handed down two decisions: the two white servants had their service time extended by a handful of years; the African-American servant, whose name is known to have been John Punch, was declared a servant for life. The first wave of indentured servants, particularly those who had sympathetic masters, made good on their contract and walked away with good supplies and goodwill, perhaps turning all of that into a livelihood that even accommodated the former servant's becoming the master. However, as more and settlers claimed more and more land, the need for indentured servants, at least on the Eastern Seaboard, diminished. Prospective indentured servants went farther and farther west. Many landowners, particularly those in the South who owned plantations, turned to a workforce of slaves to fill a growing need for unskilled labor. And, more and more workers refused to work without getting paid money. Not all indentured servants became such willingly. Some took on a period of indentured servitude in order to pay off debts. Others were criminals who either chose or were ordered to become indentured servants. Indentured servitude continued to some extent into the early 20th Century, mainly in parts of America in which skilled labor was still in demand. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White