|

|

The Great Awakening

The Great Awakening was a series of religious revivals in the North American British colonies during the 17th and 18th Centuries. During these "awakenings," a great many colonists found new meaning (and new comfort) in the religions of the day. Also, a handful of preachers made names for themselves.

The First Great Awakening is the most famous of the movements and is usually referred to as simply "the Great Awakening."

As with many movements in those days, the Great Awakening began mostly in New England. It was the time of the Scientific Revolution, when people such as Isaac Newton were becoming famous for towering works of science and Europeans were focusing on matters of logic and experience. A common focus for many people was on what could be proved by physical observation (empiricism).

Obviously, a religion would be a difficult thing to reconcile with empiricism, since so much of religion depends on faith and belief in a higher power. The Catholic Church had quite a following in the North American colonies; so did the Protestant religions. However, in the 17th and 18th Centuries, people began to find the need for getting back in touch with religion. This happened in a big way in the first half of the 18th Century.

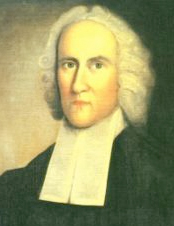

One of the prime movers of the Great Awakening was Jonathan Edwards, known mostly for his famous sermon "Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God." This fiery speech warned people against ignoring religion and its teachings and compared people's situation to a spider hanging by a thread over a hot fire. (The metaphor was that people were the spider, the hot fire was Hell, and the grace of God was the thread. If people didn't believe in God enough or do enough spiritual or moralistic things, then the thread would break and the people would fall into the pit of Hell.) The spider imagery was also telling in that from an early age, Edwards, a keen observer of nature, had written extensively on the activities of the field spider. One of the prime movers of the Great Awakening was Jonathan Edwards, known mostly for his famous sermon "Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God." This fiery speech warned people against ignoring religion and its teachings and compared people's situation to a spider hanging by a thread over a hot fire. (The metaphor was that people were the spider, the hot fire was Hell, and the grace of God was the thread. If people didn't believe in God enough or do enough spiritual or moralistic things, then the thread would break and the people would fall into the pit of Hell.) The spider imagery was also telling in that from an early age, Edwards, a keen observer of nature, had written extensively on the activities of the field spider.

Edwards, a Presbyterian minister, preached in Connecticut and Massachusetts. He is most famous for being the minister in Northampton, Mass., succeeding Solomon Stoddard, his grandfather. Stoddard is often credited with being among the first of the ministers associated with the Great Awakening, although he was eclipsed in the fame department by his grandson.

Edwards preached mostly in his home parish, unlike another famous Great Awakening minister, George Whitefield. Beginning his North American preaching career in Georgia in 1739, Whitefield soon found welcoming congregations up and down the Atlantic coast. A powerful speaker, Whitefield had much success bringing English colonists to join local churches, seeking answers to the vexing questions of the day and also finding comfort in the church's promise of eternal salvation.

Whitefield spoke both indoors and outdoors. He had a voice that carried far, and he worked himself up during his sermons, resulting in great excitement among his listeners. One outdoor sermon, in Philadelphia, is thought to have been preached to 20,000 people.

One famous fan of Whitefield was Benjamin Franklin, who published a number of Whitefield's sermons in the newspaper the Gazette.

Other noteworthy ministers of the Great Awakening were Nathan Webb, Samuel Spring, and William Tennent. It was Tennent who left his mark on the movement through education, by establishing a school for ministers (called the Log College) in Neshaminy, Penn. Tennent built the Log College into a respected institution, attracting the attention of Whitefield at one stage, and Tennent's son Gilbert carried on his father's work for many years.

In one way, the Great Awakening paved the way for the American Revolution. The "awakening" of more and more people to the teachings of various churches resulted in more people's being exposed to the idea that all people were equal under God. And if people were treated the same by God (meaning that they were "saved" if they believed in Jesus, the savior of Christianity), then those same people could certainly be treated equally by their government. This was definitely not the case in the North American colonies, which were governed by a far-away British Parliament that was holding onto many of the class-based ideals of the feudalism that had formed the basis of European culture for hundreds of years. Although Britain had a Parliament, whose members were elected, the North American colonists couldn't help elect those representatives and, therefore, had no direct method of influencing policy or laws, especially taxation schemes.

|

|