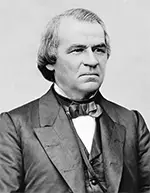

President Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson was the 17th President of the United States. He is known for ascending to the presidency after Abraham Lincoln was assassinated and for being impeached.

He was born on Dec. 29, 1808, in Raleigh, N.C. He had a brother named William. When their father died, Andrew was just 3 and his mother, with two young children, struggled to make ends meet. She found work as a seamstress and then married again. Both Andrew and William found work as apprentices with a local tailor but, after a time, ran away from home and found elsewhere, as tailors themselves. Neither boy had a formal education. They returned home long enough to move with their mother and stepfather to Greeneville, Tenn. Andrew, all of 19, married Eliza McCardle, in 1827; they had five children. Andrew Johnson turned to politics and found success as an alderman, in 1829, and then as mayor of Greeneville, in 1834. In the aftermath of the uprising led by Nat Turner, Johnson made a name for himself by campaigning for a Tennessee law that took the vote away from free African-Americans. His newfound fame propelled him to election in the state legislature. Johnson won election to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1843. A supporter of the politics of Andrew Jackson, Johnson was the first member of the Democratic Party to represent Tennessee in Congress. He served five terms in the House and then won election as governor of Tennessee. After serving two terms, he won a seat in the U.S. Senate, in 1856. He spoke out in favor of states' rights and against the abolition of slavery. He was a slave owner himself and believed that African-Americans were naturally inferior to European-Americans. He introduced the Homestead Act, which was unpopular on its face with many Southern Democrats. The bill, with substantial revisions, passed Congress but found opposition with the veto of President James Buchanan. (Congress passed and Lincoln signed something similar, in 1862.) The election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860 prompted seven Southern states, including Tennessee, to secede from the Union. Johnson, an ardent Unionist despite his support for slavery, stayed in the Senate, even though his state's other Senator, Alfred Nicholson, left Congress. After Union troops took control of Tennessee in 1862, Lincoln named Johnson military governor of his state. Lincoln further voiced his support for Johnson by naming him as the vice-presidential candidate in the presidential election of 1864. Lincoln handily won re-election, and Johnson became Vice-president. He became President on April 15, 1865, after Lincoln was assassinated. With the Civil War essentially over and Congress not in session, Johnson got to work enacting statutes by executive privilege. He pardoned many high-ranking members of the Confederate establishment, including former Vice-president Alexander Stephens. He did not move aggressively with some of Lincoln's Reconstruction policies; as a result, Southern states set up Black Codes, laws designed to keep African-Americans from achieving fundamental rights like the vote. Congress, back in session, passed the Freedmen's Bureau bill and the Civil Rights Act, both in 1866, having to resort to overriding Johnson's veto to do so. A majority in Congress were so-called Radical Republicans, who wanted to see slavery abolished and African-Americans given a number of civil rights that they had been long denied. When Congress passed the 14th Amendment, Johnson urged Southern states not to ratify it.

One of the other measures passed by Congress was the Tenure of Office Act, which gave the Senate the power to intervene if the President tried to dismiss a member of his Cabinet. Johnson, feuding with Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, fired him. In February 1868, Congress voted to impeach Johnson, making him the first President to be so targeted. The Senate voted to acquit Johnson, and he remained as President. His credibility took a big hit, however. The Democratic Party did not nominate Johnson to run for re-election (nor did he really want to run again), and he won election to the U.S. Senate in 1874. He spoke out against the continued military occupation of the South. When Congress was in recess the following summer, Johnson suffered a stroke and died, on July 31, 1875, in Elizabethton, Tenn. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White