The Filibuster

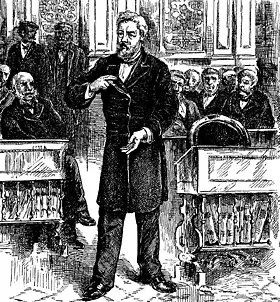

One of the most dramatic actions that a member of the U.S. Senate can take is to launch a filibuster. This is a long speech that cannot be stopped except by a vote of 60 Senators. The Senator who launches a filibuster usually wants to keep a bill from being passed. Sometimes, the goal is to draw attention to a discussion that other members of the Senate want to keep quiet. Other times, the idea is to get revisions added to a bill that is already set for a direct vote. Whatever the reason, the filibuster can be an effective tactic to call attention to both the person giving it and the issue at hand. The word itself (as is the case with many modern English words) comes from more than one language. Filibuster comes from Spanish, Dutch, and French and is most closely linked with the Spanish word filibustero, which has as its English equivalent freebooter. In the late Middle Ages, a freebooter was someone who was, in essence, a pirate, someone who freebooted something that was up to that time progressing smoothly on a set timetable. In the U.S. Senate, someone who filibusters stops the progression of a debate or a vote. The word hijack can also be applied to this situation, especially in the case of pirates. The term was first used in America in the 19th Century. It came to be part of the description of a long speech made by a Senator even though the term did not originally appear in either the Constitution or the Senate's Rules of Order.

The first well-known filibuster in the U.S. Senate took place in 1841. Senator Henry Clay was in favor of a bank bill that was opposed by the Democratic Party, which was then in the minority. Clay (whose Whig Party was then in the majority) tried to change the Senate's rules to disallow such tactics, but was soundly shouted down. The filibuster, by a series of Senators, lasted nearly a month, until March 11. Various filibusters continued to dot the Senate's history for the rest of the 19th Century. By the closer of the century, the term was in common usage. A significant addition to the principle of the filibuster came in 1917, when the Senate adopted the rule of cloture. This is the vote of Senators to stop the fiilbuster. When the cloture law was introduced, the requirement was for 67 Senators to vote to stop the filibuster. The requirement was lowered to 60 in 1949. The second half of the 20th Century saw a general increase in the frequency and length of filibusters. A number of Senators made long speeches against civil rights legislation, including one that lasted more than 24 hours. That is the record for a one-person filibuster. The multi-Senator filibuster is more common. Senators don't have to address the issue during their filibuster. They can speak on whatever they like. The history of the filibuster is filled with readings from famous literature, cookbooks, and religious works. Given the nature of the filibuster's holding up the entire proceedings of the Senate, just the threat of a filibuster can be enough for a compromise to be reached. As the 20th Century came to a close, the filibuster became a much more attractive option. The 21st Century has seen a sharp increase in the use of the filibuster, with a corresponding rise in the successful cloture votes to end those filibusters.

Social Studies for Kids |

The long, action-delaying speech is a proud part of the legislative history of many countries and civilizations throughout history. Senators in Ancient Rome uttered such long speeches. So have members of the English Parliament for as long as it has been around.

The long, action-delaying speech is a proud part of the legislative history of many countries and civilizations throughout history. Senators in Ancient Rome uttered such long speeches. So have members of the English Parliament for as long as it has been around.  Note: One of the most famous filibusters in American cinema history took place near the end of Frank Capra's iconic film Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. Star Jimmy Stewart took the floor of the Senate to protest what he saw as corruption that included a man from his own state, a man he had looked up to for many years.

Note: One of the most famous filibusters in American cinema history took place near the end of Frank Capra's iconic film Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. Star Jimmy Stewart took the floor of the Senate to protest what he saw as corruption that included a man from his own state, a man he had looked up to for many years.