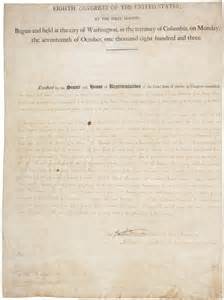

The 12th Amendment

In the Election of 1800, two Democratic-Republican presidential candidates, Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr, received the same number of electoral votes, 73. They were the top vote-getters, and so one of them would become President and the other Vice-president. But how to determine who became what? That conundrum was the genesis of the 12th Amendment. The House of Representatives eventually named Jefferson as President, but the possibility existed of a repeat performance and so Congress went to work amending the presidential election process. The result was a few changes but no wholesale alteration of the Electoral College, as some had advocated. But in completing the process that resulted in the 12th Amendment, Congress revised the Constitution's Article II, Section 1, and Clause 3.

The 12th Amendment directed the House to choose from the top three vote-getters, so that solved that problem. The 12 Amendment directed members of the Electoral College to make it abundantly clear which of their two votes was going for which candidate, so that solved that problem. (In addition, the Amendment included a Habitation Clause, which prevented an elector from casting both votes for candidates who resided in his or her home state.) Not that it had been a problem, but the 12th Amendment also directed the Senate to choose the Vice-president, from among the top two vote-getters. One key addition was that the Vice-president must be the person who had received a majority of votes cast. This provision had been stipulated for President but not for Vice-president. (It was assumed, as were many things about the process initially.) Congress proposed the 12th Amendment on December 9, 1803. Within a month, five states (North Carolina, Maryland, Kentucky, Ohio, and Pennsylvania) had ratified the Amendment. The other states followed suite during the next six months; and New Hampshire's ratification, on June 15, 1804, brought the 12th Amendment into the Constitutional fold. Until the ratification of the 20th Amendment, in 1933, Inauguration Day was on March 4. So even though presidential elections up to that time happened late in a calendar year, the new President and Vice-president didn't take office for a few months. Thus, one of the fixes of the 12th Amendment had March 4 as the date by which the Vice-president-elect would begin acting as President if the House of Representatives had still been unable to choose from among the available presidential vote-getters. (The 20th Amendment switch of March 4 to January 20 for Inauguration Day applied to this provision as well.) The provisions of the 12th Amendment have, for the most part, been unneeded. The only presidential election since 1800 that required intervention of the House of Representatives was the Election of 1824, in which a majority of electors named John Quincy Adams as President even though Andrew Jackson had received the most electoral votes initially. The Whig Party attempted to engineer a House intervention in the Election of 1836, but sitting Vice-president Martin Van Buren earned himself and his party enough existing electoral votes to thwart the Whigs' four-candidate regional strategy. The Election of 1948 and the Election of 1968 featured third-party presidential candidates who received much attention and many votes, but both of those elections still produced a decisive electoral majority. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White

One change was to narrow the number of candidates from which the House could choose a President. In 1800,

One change was to narrow the number of candidates from which the House could choose a President. In 1800,