The

Making of the 50 States: New York

Part

1: In the Beginning

The first Europeans to settle in what is now New York were from Holland and chose Manhattan Island as their home. The city that they founded was New Amsterdam, and Peter Minuit was the first director-general.

Native Americans living in the area at the time included the Algonquin, the Lenape, the Mohawk, and the Mohegan. Further north lived the Iroquois. These tribes alternately traded with one another and declared war on one another. All tribes were friendly with the Dutch, however. It was the Lenape who, as the story goes, sold Manhattan island to Minuit for $24.

The Dutch settlement prospered, so much that the Dutch West India Company began trading.

English settlers moved into the New York area in later years, most notably on the heels of the explorations of Henry Hudson (who, ironically, had discovered land and waterways while in the employ of the Dutch East India Company). The English had more dealings with Iroquois and other tribes living in the northern part of the colony.

English settlers moved into the New York area in later years, most notably on the heels of the explorations of Henry Hudson (who, ironically, had discovered land and waterways while in the employ of the Dutch East India Company). The English had more dealings with Iroquois and other tribes living in the northern part of the colony.

The dispute between England and Holland began in the mid-17th Century, after the close of the Thirty Years War. Both countries wanted control of shipping on the high seas and colonies in new lands, like North America. English settlements dotted the Eastern Seaboard, with the notable exception of New Netherland.

In 1664, England claimed the entire continent (what was then known of it) for itself and proceeded to harass the Dutch fort at New Amsterdam. The Dutch, under leader Peter Stuyvesant, put up very little of a fight, and New Amsterdam became New York. It wasn't just New York, either. Fort Orange became Albany, and the rest of the Dutch territories in the New World were ceded to England.

The two countries continued skirmishing in Europe, and the Dutch briefly regained their North American territories; but by the close of the 17th Century, the Dutch era, at least in a settlement way, had passed. (Ironically, the King and Queen of England near the end of that century were William and Mary, of Holland.)

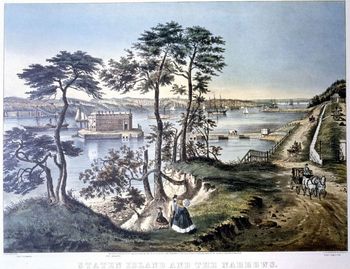

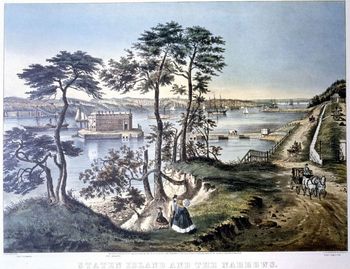

The English consolidated their hold on the New York colony in the 18th Century, importing royal governors and installing English societal  traditions. The port of New York City grew into a major shipping presence, with American goods heading out daily to the Mother Country and receiving all manner of cargo from England, other European countries, and the Caribbean. (This was the popular Triangular Trade.)

traditions. The port of New York City grew into a major shipping presence, with American goods heading out daily to the Mother Country and receiving all manner of cargo from England, other European countries, and the Caribbean. (This was the popular Triangular Trade.)

As the population and trade income of the New York colony increased, so did the variety of its commerce. Agriculture and fishing were natural commercial pursuits. Tobacco became a big business as well.

One thing the New York settlers enjoyed under English rule was religious freedom. Dutch authorities hadn't been so accommodating when it came to houses and methods of worship.

Another sort of freedom was ironed out in 1735. This was a certain kind of freedom of the press, the freedom from debilitating libel suits. John Peter Zenger, publisher of the New York Weekly Journal, printed information about New York's governor, William Cosby, that Cosby didn't particularly like. Under the laws of the time, Cosby was able to have Zenger arrested and put in jail just for printing such things (even if they were true). In a landmark trial, Zenger was found not guilty, thanks in large part to a spirited defense by Andrew Hamilton.

Other noncommercial advances included a postal service, not only throughout the city but also to other cities, such as Boston; and the establishment of six prominent universities, the last of which was King's College (now Columbia), built in 1754.

Next

page > War, Taxes, and Peace

> Page 1, 2

|

English settlers moved into the New York area in later years, most notably on the heels of the explorations of

English settlers moved into the New York area in later years, most notably on the heels of the explorations of  traditions. The port of New York City grew into a major shipping presence, with American goods heading out daily to the Mother Country and receiving all manner of cargo from England, other European countries, and the Caribbean. (This was the popular

traditions. The port of New York City grew into a major shipping presence, with American goods heading out daily to the Mother Country and receiving all manner of cargo from England, other European countries, and the Caribbean. (This was the popular