The Viceroyalty of Peru

Part 2: From Spanish Imprint to Independent Territories Circling outward from the centralized viceroyalty were a number of audiencias, tribunals that served both administrative and legislative duties and that oversaw hundreds of districts, which were run by either a corregidor (mayor equivalent) or a cabildo (town council equivalent). An 18th Century switch from the corregidor to the intendant, higher-ranking officials with broader powers, caused a fair amount of tension among the various layers of government. The Crown reshaped the people into four classes:

A powerful motivator of the continued exploration and occupation of the New World was the spread of Christianity. Missionaries fanned out throughout the lands, spreading the word and gaining converts, many times forcibly. People in reducciones were a captive audience and also left behind both the vestiges and the gathering places of their native religion. One powerful way that the Spanish emphasized their status as conquerors was to build churches on the ruins of Inca temples that they had destroyed. As the years went by, Spanish leaders and soldiers solidified their hold on the former Inca lands, expanding their reach and defending what they had conquered against incursions by English and Dutch raiders. Cities like Lima and Trujillo got city walls. Port cities like Arica, Callao, Valdivia, and Valparaiso got fortifications and more ships. All of that occupation, forced resettlement, and forced religious conversion was not without resistance. Many times during the Spanish occupation, indigenous people rose up in revolt. Most of those were small in scale and not backed by weaponry enough to make a difference. One that succeeded was led by Juan Santos Atahualpa, who in 1742 set off a rebellion of the Ahaáninka people that claimed a significant amount of land, repulsed a number of Spanish military expeditions to repress it, and ended only when the rebellion leader himself disappeared, in 1752. Another well-known successful rebellion was that led by Túpac Amaru II, who struck back at Spanish forces in and around Cuzco in 1780 with a force of tens of thousands and held out for more than a year; the rebellion continued for a year after his capture and execution.

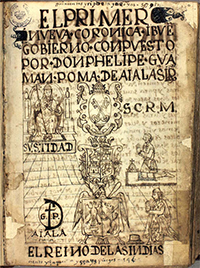

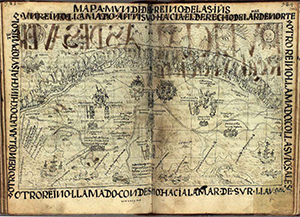

One primary record of the various injustices that indigenous people felt that the Spanish had visited on them was El primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno (The First New Chronicle and Good Government), a very long letter from an indigenous man named Guaman Poma to King Philip III of Spain. Poma, an administrator and scribe, lived through most of the 16th Century and chronicled his people's experiences at the hands of the Spanish in a series of words and illustrations. He also proposed that the existing Spanish government and its resulting New World society be reorganized, more along the lines of the way that indigenous people had ruled themselves. He wrote in four In the 18th Century came large-scale changes in administration. In 1717, the Crown created the Viceroyalty of New Granada, from the former Colombia, Panama, Venezuela, and parts of Ecuador, Guyana, and northern Brazil. In 1776 came the Viceroyalty of the Rio de la Plata, from what is now Argentina, Bolivia, Paraguay, and Uruguay. Spanish occupation was not without its elements of civilization and learning. Charles V in 1551 established the National University of San Marcos, in Lima. A number of viceroys expanded the offerings therein. Appearing in the capital city in 1709 was a literary academy and in the 1780s a Botanic Garden. Lima had a thriving arts community, buoyed by theaters, newspapers, and an academy of fine arts. In the realm of painting, the Italian artist Bernardo Bitti arrived in Cuzco in 1583 and stayed for a time, sharing European trends with indigenous and Spanish painters both. One of the Cuzco's most famous native painters was Diego Quispe Tito.

As happened in Mexico, a drive for independence from Spanish rule began in the south in 1810 and eventually succeeded. Led by Joséde San Martin, Simón Bolivar (right), Thomas Cochrane, and others, the Expedición Libertadora occupied Lima, in July 1821. A week later, on July 28, Peru was independent. That was a technicality, of course, since Spain hadn't given up on ruling the rest of the Viceroyalty of Peru. The fighting continued for another three years, with the final two revolutionary victories coming at the Battle of Junin, on Aug. 6, 1824, and the Battle of Ayacucho, on December 9 of that same year. The final capitulation came from Viceroy José de La Serna, whom revolutionary forces had captured in the aftermath of the battle. First page > Conquest and Administration > Page 1, 2 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

languages–two European (Latin and Spanish) and two indigenous (Aymara and Quechua). The letter also includes a mappa mundi (map of the world). Poma wrote the 1,189-page document (398 of which are illustrations) on and off between 1600 and 1615. He never sent it to the king.

languages–two European (Latin and Spanish) and two indigenous (Aymara and Quechua). The letter also includes a mappa mundi (map of the world). Poma wrote the 1,189-page document (398 of which are illustrations) on and off between 1600 and 1615. He never sent it to the king.