The Roman Emperor Trajan

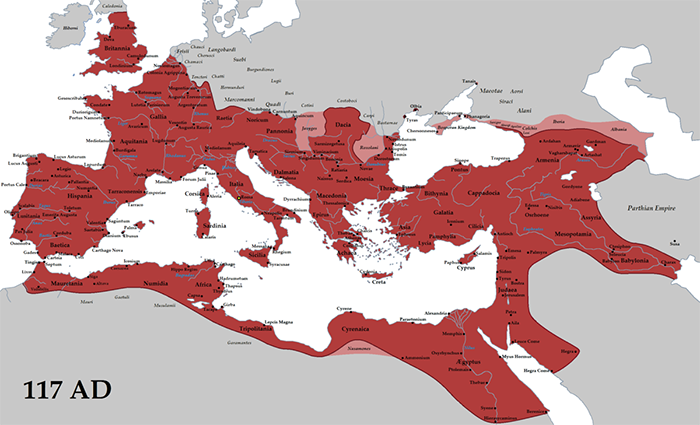

Trajan was the second of the so-called Five Good Emperors, a string of Roman rulers in the 1st and 2nd Centuries. Trajan is known for being the emperor who ruled over the Empire's greatest territorial extent.

He was born Marcus Ulpius Traianus on Sept. 18, 53 in Italica, what is now Seville. He was named after his father, a successful commander, consul, governor, and Senator. He led troops into Judea during the First Jewish Revolt, in 67–68. While he was governor of Spain, his son joined him, serving in the Seventh Legion while also holding the office of tribune. In 89, Trajan marched with the emperor Domitian to put down a revolt led by Saturninus, the governor of Upper Germany; for his reward he earned from the emperor a posting as praetor and then, in 91, as consul. A group of assassins killed Domitian in 96, and Nerva took the throne. The new emperor named Trajan governor of Upper Germany and, a year later, formally adopted him, designating him as heir to the throne. Far more at home in the military than in government, Trajan stayed with his army for a time when, in January 98, he got word that Emperor Nerva had died. Trajan took time to inspect the frontiers along the Danube and the Rhine. He also had a bridge over the Danube River; it was the longest arch bridged in the world for a century. He returned to Rome in summer 99 to great acclaim, not least because he came on foot and presented himself to the people at large.

He set about undoing some of the harm done by Domitian, recalling people in exile and setting free a number of political prisoners. After a period in which emperor and the Senate got to know each other, Trajan set out again for the frontier, to do battle with the Dacians. He dealt them a stinging defeat at Tapae in 101 and, after another skirmish, convinced them to ask for peace. Trajan got from King Decebalus what Domitian had not: land, in the form of a large amount of territory north of the Danube. The peace agreement last for a time, but the restless Decebalus rose up again in 105, and Trajan was back in the fray. The result was the same again, with Trajan capturing the Dacian capital, Sarmizegethusa, and sending all of the royal treasury back to Rome as a prize. Trajan seized the head of Decebalus, who had committed suicide, and took it back with him to Rome, where it went on public display. Trajan not only annexed Dacia but also sent a large number of Romans to live there. A victorious Trajan ordered a series of gladiatorial games in Rome to celebrate his victory. For six years, Trajan enjoyed the fruits of his labors and a peaceful rule. During this time, he ordered built two large construction projects, the Forum of Trajan and Trajan's Column. The former incorporated two six-story buildings that housed halls and offices and served as the center of a hub for economics, government, and religion. The latter was a 100-foot-tall stone column that commemorated his victory over the Dacians; on top were a statue of the emperor and a viewing platform, up to which led a stairwell. He also oversaw the building of new aqueducts, baths, roads, and temples. War came again in 114, when the Parthians meddled in the affairs of Armenia. Trajan, at the head of an army, made that land a province of Rome and then carried on southward, annexing Mesopotamia, and even seizing Ctesiphon, the capital of Parthia. This led to Trajan's status as the emperor on whose watch the boundaries of the Empire stretched to their widest extent. From Scotland in the north to Egypt in the south, from Mauretania in the west to the Caspian in the east: Roman armies and governors ruled all.  Those boundaries didn't last long. In 117, the same year in which Rome annexed Mesopotamia, that province rebelled, as did Cyprus and Egypt. Trajan waded into the fray, determined to put down yet another rebellion. Hearing of trouble in the north, he headed back to Rome. He never reached the Eternal City, falling ill in Cilicia, where he died, on Aug. 9, 117. He had been married, to Pompeia Plotina, for more than 20 years; they had had no children. He had provided well, however, adopting his cousin's son as his successor. Hadrian followed him on the throne.

|

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White