The Ten Days' Campaign

The Ten Days' Campaign was a Dutch military attempt to suppress the Belgian independence bid of 1830. Although the Dutch had military superiority, their efforts were eventually unsuccessful. The Low Countries had been together under various foreign entities for centuries. In the modern era, however, divisions between north and south emerged. The advent of the Reformation and the Protestant movement created a nominal territorial divide that saw the southern provinces remain predominantly Catholic while the northern provinces became a haven for practicers of many types of Christianity and other religions as well.Another division that had geographical causes was the proximity of the southern provinces to neighboring France. The Franks, Carolingians, and Holy Roman Empire had ruled over all of the Low Countries, introducing French and German as official languages along the way. Dutch grew in usage in both north and south but was much more preferred in the north and, in some cases, was the state language. (Naturally, that didn't sit well with the large number of French speakers in the south.) As well, in the 19th Century United Kingdom of the Netherlands, representation was skewed mainly (and sometimes heavily) toward the north. Even though the south had a higher population, the northern interests were more widely and populously represented in government. Conversely, debts incurred by the north were repaid by the central government, to which all citizens paid to help eradicate those debts. It was King William I who accelerated this exacerbation by prioritizing the Dutch language and most things north at the expense of southern interests. Another source of strife was the discrepancy between militia recruitment rates and officer distribution. On average, more from the south were recruited into the militia and more from the north were officers. As well, by the 1820s, the official language of the Dutch Army was Dutch, and so those who spoke mainly French or another more southern language had to learn Dutch in order to serve in the army. Dutch armies had fought against France in the War of the First Coalition. King William I had fought against France, in several significant battles. Unsurprisingly, the southern provinces sympathized with their neighbor France. In the same year that France found its final defeat, at Waterloo, William I took the throne of a new kingdom. This was the birth of the modern country. William antagonized people in the southern provinces, however. Finally, in August 1830, people in the southern provinces had had enough and rebelled. Large numbers of Belgian soldiers left the Dutch army. Not all of these took up arms to defend the new Belgian state, but some did. As well, the Dutch armed forces were rather stretched defending overseas possessions. Nonetheless, when William I decided to deploy troops to bring Belgium back into the fold, he had an army that some sources say numbered as many as 50,000. Even conservatives estimates say that Dutch forces well outnumbered Belgian forces, which were estimated at 24,000. The Dutch king was hoping for a nonviolent solution and believed that his sending troops into the southern provinces would be enough to seal the deal. He was mistaken. The Belgians split their defense forces in two, the Army of the Meuse and the Army of the Scheldt. The newly minted Belgian king, Leopold I, commanded the latter.

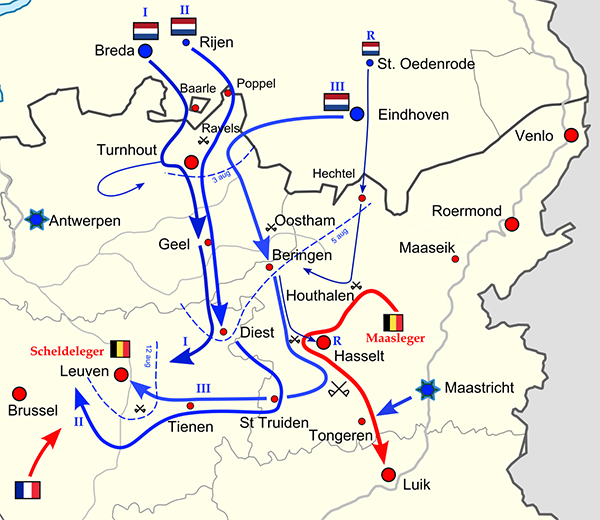

Dutch troops under Crown Prince William crossed the border on August 2, 1831. Fighting took place near Nieuwenkerk and Zondereigen. Dutch success near Ravels drove the Belgian defenders to retreat to Turnhout. The following day, the first large battle of the campaign took place. A large Dutch force marched toward Antwerp while the main force confronted the settlement at Turnhout. The Antwerp-bound troops instead joined the main fray and the Dutch took Turnhout. The next day, they seized Antwerp. William's forces had little trouble defeating the defenders, defeating both main Belgian armies at regular intervals. The end of the independent state of Belgium seemed imminent. A desperate Leopold appealed for help from other European powers, on August 8. The Belgian representative to the U.K. court, Sylvain Van de Weyer, pleaded his case but found deaf ears. His counterpart at the French court, François Lehon, foun rather more success. A large army commanded by Marshal Étienne Gêrard marched straight into Belgium. Estimates are that this army numbered tens of thousands, perhaps even 70,000. Whatever their final numbers, they were more than enough to convince the Dutch force to retreat. The only troops that remained were those in control of the citadel at Antwerp. The Great Powers of Europe that weren't the Netherlands gathered in London and approved Belgian independence. Further, the Dutch king ordered David Hendrik Chassé, his commander in Antwerp, to fire on the city. The ensuing bombardment resulted in the deaths of many people and the destruction of many homes. An exasperated France again sent troops into Belgium, this time besieging the Antwerp citadel. Belgian forces had not stopped fighting during this time, but it took the French infusion to break through. After nearly a month, General Chassé surrendered, on December 23, 1832. It took another seven years for William I to formally agree to recognize an independent Belgium; however, he sent no further troops southward. In the end, the Ten Days' campaign did not achieve its goal.

|

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White