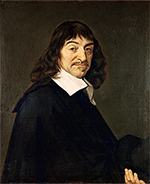

The Revolutionary French Thinker René Descartes

Frenchman René Descartes was one of the most famous scientists and philosophers in the history of Western Civilization.

He was born on March 31, 1596, in La Hay en Touraine, near Tours. His father, Joachim, was a Court of Justice lawyer. His mother, Jeanne, died a year after René was born, and the boy and his two siblings went to live with their mother's mother, Jeanne Sain. Young Renée suffered from ill health, which included a persistent cough, and his father paid for a nurse to look after him. Joachim Descartes worked for half the year at the Court of Justice in Rennes. He remarried when Renéwas 4 and stayed in Rennes. Joachim was also a member of the provincial parliament. Even though their father was not with them, the Descartes children enjoyed a good quality education. René went to a Jesuit boarding school in La Flèche when he was 8; he stayed there for seven years. He excelled at many subjects, among them astronomy, grammar, logic, mathematics, music, philosophy, physics, rhetoric, and theology. He achieved all of this despite his continual ill disposition; his school elders allowed him to stay in bed later than other students. He continued his studies at the University of Poitiers, earning from that institution a law degree in both church and civil law in 1616. Instead of going straight to work, Descartes traveled around France, spending a considerable amount of time in Paris. He enrolled in the Dutch States Army and studied at a military academy, focusing on engineering. In 1618, Descartes met the Dutch philosopher and scientist Isaac Beeckman, who presented many challenging problems for his curious, thoughtful student. It was on Nov. 10, 1619, in Ulm, that Descartes said that he had a number of dreams that spurred him to revolutionize the way that scientists thought and worked. The subjects of these dreams were analytic geometry, philosophy, and the Scientific Method.  He moved back to the Netherlands in 1628 and spent more than two decades there, studying at Leiden University. In that time, he worked feverishly on coalescing his thoughts and ideas into a new way of looking at the world. He began with The World, a treatment of science that included an argument in favor of the heliocentric theory of the solar system (although he did not publish this, for fear of reprisals from the Catholic Church). He concluded another pair of essays and then, in 1637, published one of the most famous works in all of Western literature, The Discourse on Method. Two years later, he started on another very famous work, Meditations on First Philosophy. To this he later added Principles of Philosophy. Descartes asserted that all truths were ultimately linked and urged people to look at the world through rational eyes and to start from a mindset of skepticism and doubt. He distilled his very existence to an aphorism that is very familiar to a great many people: "I think; therefore, I am." Another tenet of his thinking was to order thoughts from simplest to complex, in order to build to a logical conclusion. In the same way, he encouraged those wanting to solve a problem to spread it out into as many parts as needed in order to find the best solution. This idea infused his theory of physics, in that all physical phenomena, he thought, were made up of a collection of the tiniest parts (as in atoms). These ideas illustrated the metaphor of the tree that Descartes used to describe his holistic view of philosophy. “The roots are metaphysics, the trunk is physics, and the branches emerging from the trunk are all the other sciences, which may be reduced to three principal ones, namely medicine, mechanics and morals,” he wrote. He approached all of these ideas from a rational, scientific, logical, and mathematical point of view. He firmly believed in the idea of a mind-body dualism, that the mind and the body were separate entities that were, nonetheless, closely linked. The essence of the mind was thinking, he wrote; the essence of the body was feeling (and, therefore, not thinking). Further, the mental could exist outside the body. Descartes grounded his thinking firmly in thought, in rationality. Perceptions were notoriously unreliable, he argued, and so should not be relied on as evidence of proving something. More to be trusted were reason and logic.

Descartes also revolutionized mathematics, with the assertion in La Géoemétrie that he coulld convert geometry problems into algebra in order to find a solution. Illustrating this was the system of drawing a curve on a graph, turning a three-dimensional shape into a two-dimensional representation of that shape. Descartes himself did not use the letters x and y, but the system that employs them is called the Cartestian coordinate system. This radical insight displaced centuries of thinking of mathematicians who had slavishly followed the teachings of Aristotle. To Descartes also goes the innovation of writing exponents of variables as superscript numbers. What had been written a.a.a became a3. Going further, Descartes illustrated how to find the tangent of a curve, anticipating the differential calculus developed by Gottfried Leibniz and Isaac Newton. Descartes moved to Sweden in 1649, so he could set up a new science academy and serve as the philosophy tutor of Sweden's Queen Christina. He never married but in 1635 did have a daughter, Francine, who was 5 when she died of scarlet fever. Descartes himself died of pneumonia on Feb. 11, 1650, in Stockholm; he was 53.

Other works by Descartes:

Famous quotes by Descartes:

|

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White