The Punic Wars: Titanic Struggle in the Ancient Mediterranean

Part 2: The First and Second Punic Wars Most historians date the start of the First Punic War to 264 B.C. It was in this year that Rome, under Consul Appius Claudius Caudex, captured Messana. Rome followed with more victories but eventually realized that an enhanced military effort would be needed to conquer the entire island of Sicily. Roman naval technology wasn't nearly as advanced as Carthage's at this time, and Carthage had more ships as well, and they certainly were experienced sailors.

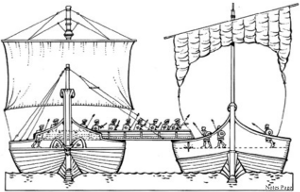

Roman ingenuity solved the problem by changing the situation, employing a movable wooden-and-metal bridge called a corvus to turn a sea war into a land war: A Roman ship would get close enough to a Carthaginian ship to "connect" the two, using the corvus, and then Roman soldiers would storm aboard the Carthaginian ship and press the Roman advantage in hand-to-hand combat. This strategy was effective at Mylae, in 260, and several times thereafter. Even so, Carthage defended the western part of the island for several years more. Finally, a combination of violent weather (which claimed a large number of Carthaginian ships) and Rome's greater ability to produce new armed and naval forces resulted in Roman victory, with the two sides signing a peace treaty in 241. Carthage gave up all claims to Sicily and paid Rome a lot of money.

Not long after, Carthage was forced to go to war with its own mercenaries, who had taken the end of the war with Rome as opportunity for an uprising. The Mercenary War lasted nearly four years, during which time Rome occupied Corsica and Sardinia, both Carthaginian colonies. Also at this time, Carthage, under General Hamilcar Barca, had taken over much of Spain. Hamilcar's son Hannibal was made supreme commander of Iberia (Spain). In 219, Hannibal attacked Saguntum, a Roman city, in what is now Valencia. This triggered the Second Punic War. Historians date the beginning of this war to 218. This time around, the odds were stacked again in Rome's favor in that seapower between the two civilizations was about equal, meaning that Rome had neutralized Carthage's former advantage; further, Roman advances of late had included some improvements on earlier fighting ships, meaning that Rome had actually pulled ahead of Carthage, both in technology and in manpower. Roman ships now outnumbered Carthaginian ships. Hannibal the Rome-hater would have to find another way to take the fight to the enemy.

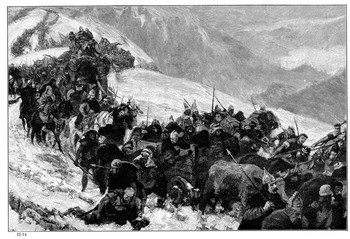

That is exactly what he did. In a master stroke of military strategy that was as unconventional as it was daring, Hannibal made the courageous and outrageous decision to cross the mighty Alps with his invasion force, choosing to attack Rome by land rather than by sea. He massed an army of 60,000 in Spain and then set out across Gaul (what we now call France). He gained some troops along the way, from tribes that hated Rome. The Carthaginians also faced resistance from some mountain peoples who were allied to Rome. What is all the more amazing is that he brought with him not only an army but all the equipment that would be needed to support that army–food, water, supplies, armor and weapons. He also included in that fighting force his standard battlefield complement of war elephants, which could scare an enemy force from the field just by mounting a charge. Next page > The Rise and Fall of Hannibal > Page 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White