Nero: Emperor of Rome

Nero was Emperor of Rome in the 1st Century. He ruled for more than a decade, overseeing lavish buildings projects and first pleasing and then alienating the people and the army. He is perhaps most well-known for his questionable role in the events surrounding the Great Fire of Rome.

He was born in 37. His name at birth was Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus. His father, Gnaeus Domitius, died when the boy was 3. When Lucius was 12, his mother, Agrippina, married Claudius, then the Roman Emperor. At that time, Lucius changed his name to Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus. Claudius adopted Nero in 50. The well-known philosopher and playwright Seneca taught Nero, who studied subjects such as philosophy, rhetoric, and Greek. Claudius died in 54, after eating poisoned mushrooms. Historians have long suspected that Agrippina and perhaps even Nero participated in or at least knew about the feeding of the poisoned mushrooms to Claudius. When Claudius died, his successor was not Brittanicus, his son, but Nero, his adopted son. Nero was all of 17 when he became emperor. Nero set about rolling back some of the reforms that Claudius had put in place, reducing taxes and putting on lavish public games and spectacles, such as chariot races and gladiatorial tournaments. Plays and music were part of Nero's preferred entertainment. He himself liked to sing and play the lyre; historians tell us that he had little talent at either. It was a standard commitment that all who attended a musical performance given by the emperor were required to stay until he was finished. Whether they enjoyed the performance or whether they attended of their free own will was beside the point. Despite or because of Nero's popularity, his mother, Agrippina, was jealous. She considered herself the power behind the throne, if not the power of the throne, and boasted of this publicly. At first, she had assumed some of the powers of the throne, receiving embassies and dealing with state correspondence; she was even on royal coins for a time. But Nero very much wanted to be in control. He moved his mother out of the royal palace and then removed her army protection. Realizing that she could no longer control her son, she threw her support to her stepson, Brittanicus. He, too, died of poison, in 55. Nero, in the end, ordered his mother's execution. After two failed attempts at an elaborate method of murder, he ordered her stabbed to death in 59. The ordering of his own mother's murder marked a change in Nero. He began to order large amounts of money spent on things for himself and his palaces and for public spectacles. He also brought back capital punishment, which he had recently outlawed, and used it against perceived enemies, even people who spoke unkind words about him. Nero was married twice. His first wife was Octavia, whose father was Claudius. Nero decided that he wanted to marry someone else, a married woman named Poppaea, and so divorced his own wife and sent Poppaea's husband, a soldier, far away. That marriage proved an unhappy one, and Nero killed his second wife by accident after an argument. Perhaps Nero's greatest challenge came in the face of a natural disaster, the Great Fire of Rome. Historians have long have varying versions of what part he played before, during, and after the blaze.

For six days in July 64, the city of Rome was consumed by fire. Summer temperatures and winds were already high; many buildings were made of wood and poorly constructed; and, according to some sources, high-ranking officials hampered efforts to control the blaze. As a result, many people died and 10 of the 14 city regions were either heavily affected or ruined. To this day, historians cannot agree on some basic elements of the story, including who, if anyone, might have caused the blaze. Rome at that time was a city of 2 million people, many of whom were poor, living in slums. It was in one of these areas, at the Capena Gate, a marketplace near the huge stadium Circus Maximus, that the fire began, late on the night of July 18. The stadium quickly went up in flames, as did a large part of the city. Hot summer winds fanned the flames. Looting was widespread. Thousands were left homeless and penniless. After six days, the fire dropped to a fizzle. In the aftermath, Rome rebuilt, following a blueprint set out by Nero.

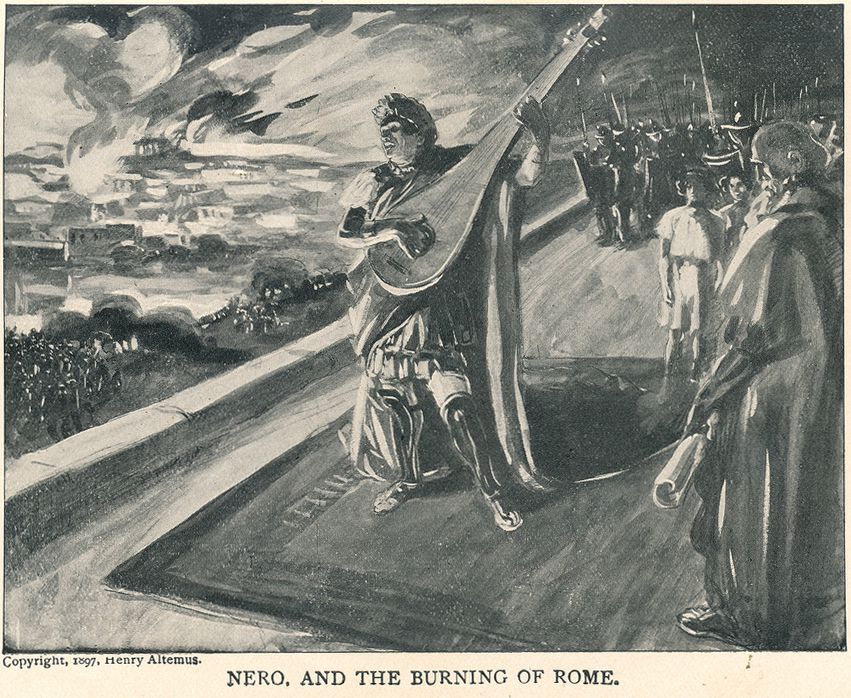

The emperor wasn't in Rome when the fire began, according to most historians, including Tacitus. Rather, he was in the resort town of Antium. Some historians say that he rushed back to Rome when he heard about the fire and offered much assistance to people displaced by the fire. One source says that he personally pitched in to try to fight the fire. However, one of the most commonly mentioned elements of the saga of the Great Fire of Rome is that Nero sang and played his lyre, as if celebrating the burning of the city. Cassius Dio writes that Nero grabbed his lyre, climbed to the roof of his imperial palace, and belted out a song called "Capture of Troy" while watching the flames grow. Another historian, Suetonius, echoes that sentiment, placing Nero in a different place in the city and singing a slightly different song but still playing the lyre and generally ignoring the devastation all around him. Many students of history rely on these three historians for a great many details about Rome, its people, and its famous and mundane events. Another source, Flavius Josephus, didn't mention the Great Fire at all in his writings about Nero. What is known is that among the buildings destroyed by the fire were a great many residences, including those of many aristocrats and Senators and the Domus Transitoria, Nero's personal palace, which was very large indeed. The fire also destroyed a large part of the Forum, home to the Senate and the government.

Nero had wanted to see a large part of the city torn down so he could have constructed a series of palaces known as Neropolis. Out of the ashes of devastation wrought by the Great Fire, Nero had constructed a great palace known as the Domus Aurea. This new palace complex was expansive (covering nearly 100 acres), full of gold-plated ceilings, exotic animals, and sported a very large lake. In the center was a 100-foot-tall bronze statue of Nero, known as the Colossus Neronis. To finance all of this construction and augmentation, Nero ordered new taxes and large-scale confiscations of money and property from people suspected of treason. Nero himself blamed someone else for starting the blaze. Several sources, Tacitus among them, say that Nero blamed members of the relatively new faith known as Christians for starting the fire. Certainly, after the Great Fire, Nero endorsed and encouraged the persecution of Christian people in Roman lands. This persecution extended to execution, and Nero widened his target field to include his political opponents. Despite his initial popularity, Nero, now a figure of ridicule to some and figure to be feared by others, found himself the target of conspiracies. The Piso Conspiracy was a large-scale attempt to kill the emperor, perpetrated by nearly two dozen senators and other leading officials; Nero had most of those involved executed. As well, when the inevitable rise in taxes came about, people in outlying provinces like Gaul and Judea revolted and contingents of soldiers were required to put down the revolts. Another large-scale revolt during Nero's reign happened in Britain, when the Iceni queen Boudicca succeeded in rallying a large number of Britons to her side; the resulting rebels killed thousands of Romans before the Roman Army turned the tide and put down the rebellion. At this time, Nero traveled to Greece and spent a good amount of time. He drove a chariot during the Olympics and announced a plan to dig a canal across the Isthmus of Corinth. Closer to home, the governor Gaius Julius Vindex rebelled in 68. Gathering support, he recalled another governor, Servius Sulpicius Galba, to join in the rebellion. The plan was for a large number of people and soldiers to rise up, overthrow Nero, and install Galba as emperor. The emperor was successful at putting down the rebellion, but only just: His own bodyguards declared their allegiance to Galba. Nero tried to flee Rome but could convince neither bodyguard nor soldier to go with him and so returned to his palace. After hearing that the Senate had condemned him to death, he decided to do the deed himself; in the end, he couldn't finish himself off and convinced his secretary, Epaphroditos, to finish the job. Nero's final words were said to have been, "What an artist dies in me!"

|

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

Nero is one of the people who gets blamed for the fire damage, either by ordering the fire started or ordering soldiers to keep it burning. The theory goes that Nero wanted to see many new buildings constructed but, seeing his plans stymied by the Senate, resorted to other means to make way for his new construction.

Nero is one of the people who gets blamed for the fire damage, either by ordering the fire started or ordering soldiers to keep it burning. The theory goes that Nero wanted to see many new buildings constructed but, seeing his plans stymied by the Senate, resorted to other means to make way for his new construction.