John Harrison: Solver of the Longitude Problem

John Harrison was an English tradesman and inventor who solved one of the most thorny problems of the Age of Navigation: how to calculate longitude at sea. During the Age of Exploration, European countries sent ships all around the world, in search of new lands and new opportunities for expansion. Many of these voyages went where few or no men had gone before, and so ship captains and navigators needed to keep track of where they were in order to get where they wanted to go. One of the oldest methods of doing so was dead reckoning, or determining the position of a moving object by compared it to the known position of a fixed position. Someone using dead reckoning had to have an accurate map showing that fixed position, of course, not to mention accurate measurements of current speed and, in the case of a ship at sea, some knowledge of the strength of the ocean currents. In other words, it was a tall order.

Voyagers carried with them a succession of devices designed to help them accurately further their travels. One such device was the cross-staff, a pole with length markings that a navigator could use to measure angles. A modern version of this was the sextant (right), which improved accuracy considerably. Another tool available to such navigators was the astrolabe (left), a metal disc-shaped device that was something of a star chart, to be used to calculate a fixed position on Earth based on what the observer could see in the night sky, and then compared to the markings on the astrolabe.

One very useful device that every successful ship's navigator had at the ready was a compass, which determined location based on a grid of north, south, east, and west. The compass is a very old invention. It dates to the Han Dynasty, which ruled China for two centuries on either side of the year 0. But people in those early years of compass production used those devices for divination and nothing else. It was centuries later, during the Song Dynasty, that Chinese scientists used a compass for navigation. Chinese armies are known to have used a compass to navigate on land as early as the 11th Century and to navigate at sea as early as the 12th Century. It was in the Middle Ages that the first fairly accurate world maps were published. Voyages then used these as their guides in sailing the ocean blue. They could look at such maps and calculate their relative latitude, the north-south position of a point on the surface of Earth. Still eluding them was a reliable means of calculating longitude, the east-west position. Some ancient maps had a rudimentary system of both latitude and longitude. Both Eratosthenes and Ptolemy included the dual approach. Neither of those, however, proved accurate when sailing the wilds of the oceans. The New World voyages of Christopher Columbus created a wave of interest in furthering such explorations, and the nations of Europe competed for supremacy in this new arena. All recognized the importance of finding the ability to calculate longitude at sea. Some nations' monarches offered money as an incentive for some clever inventor to determine how to do it. The first of these was Spain's King Philip II, in 1567; sweetening the pot was his son, Philip III, who offered a lifetime pension in addition to a cash prize. The Dutch government got into the act, as did the British government. In fact, Britain established the Royal Observatory in 1675 with the express purpose of achieving the long-held goal.

It wasn't until 1714 that the British government set out a reward. By that time, several brilliant minds throughout Europe had been hard at work, without success. John Harrison (right), a carpenter and clock-maker from Yorkshire, in the north of England, put his expertise to work on the problem. It took him 30 years, but he finally solved it. Harrison followed in the footsteps of his father, also a carpenter and clock repairman. Harrison enjoyed music as well and was at one time choirmaster at his local church. However, it was at making clocks that he especially excelled. He was just 20 when he built his first grandfather clock. A few yeas later, he replaced a turret clock with a mechanism so efficient that it works to this day.

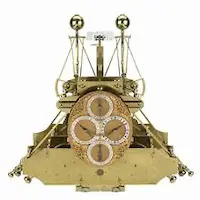

Earlier attempts had focused on celestial navigation. No less a brilliant mind than Sir Isaac Newton had voiced doubt that a clock could ever be produced with enough accuracy to allow precise calculation of longitude. Harrison, a clock-maker by trade, naturally focused on that as a solution. He developed a chronometer to take aboard ships at sea in 1735. The testing of this device, now called H1 (left), was a trip from England to Lisbon, Portugal, and back, aboard first the Centurion and then the Orford. The results were of a very high accuracy. However, in order to receive the prize, Harrison had to convince a board that the British Parliament had set up to judge the veracity of claims by possible winners. The board had offered a top prize of £20,000 for a device that produced outstanding accuracy. Harrison, the board determined, wasn't quite there yet; however, the board granted him a prize of £500 in order to finance another attempt. He made two more models, H2 and H3, tweaking the original slightly each time. However, neither model went for a sea test because Britain had become involved in the War of the Austrian Succession.

Harrison went back to basics, producing a pocket watch in 1753 that then proved the inspiration for the H4 (left), a much smaller and lighter device that he presented to the board in 1759. As a prerequisite, Harrison's son William had taken it on a trip to Jamaica and back. The chronometer showed enough deviation that the board asked Harrison to dismantle the H4 within their sight and explain to them exactly how it worked. They refused to give him the prize money. Harrison continued to fight for it, addressing Parliament in 1765 and gaining half of the total. He persisted, building yet another model, the H5, which he showed to King George III himself. Still the board held the rest of the prize money. The king argued on Harrison's behalf, and the board granted him another ?, this only in 1773, long after his initial demonstration of the H4. Harrison died three years later, without having ever been given the rest of what he was owed. The year before, 1775, the explorer James Cook had verified the accuracy of Harrison's H4, a copy of which he had taken with him on his second and third voyages to the South Pacific. Harrison's H4 chronometer, a larger than normal size pocket watch, proved to be the first of many devices that could help navigators more accurately calculate longitude at sea. As such, it was an innovation that stands out in the annals of maritime history. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White