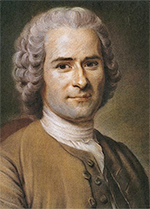

Jean-Jacques Rousseau: Philosophe, Champion of Equality

Jean-Jacques Rousseau was an 18th-Century thinker and writer whose ideas inspired the leaders of the Enlightenment and the French Revolution.

He was born on June 18, 1712, in Geneva. His mother, Suzanne, died just a week after he was born, and hs grew up under the tutelage of his father, Isaac. A watchmaker, Isaac Rousseau was also a believer in a classical education but thought that he could do it himself. Father taught son for 10 years, including reading to him from the Lives of Plutarch, until Isaac fled the city in the face of imminent arrest stemming from a quarrel with a captain. Young Jean-Jacques stayed in Geneva with an uncle for a time, lived with a cousin in Bosey, and then found work as an apprentice to an engraver back in Geneva. Finding his master to be demanding, Rousseau went to Turin, where he found work as a servant, and then to Annecy, where he found work teaching and playing music. He moved to Paris in 1742 and found work there as a composer and a musician. Rousseau came up with a new system of musical notation. The Academy of Sciences wasn't interested, but Rousseau did at this time meet another leading philosophe, Denis Diderot, who employed Rousseau to write articles on music for his Encyclopédie. (He later wrote an entry on political economy.) After serving at the French Embassy in Venice, he returned to Paris, where he met Therese Levasseur, whom he married. They had five children together and reared none of them. In 1749, Rousseau entered an essay contest run by the Academy of Dijon, which asked contestants to answer the question, "Has the restoration of the sciences and arts tended to purify morals?" He won the contest (even though he made a strong argument to support his answer of "No"), making him famous. The next year, he published his essay, as Discourse on the Arts and Sciences. He published his essay three years later to another contest run by the same academy, as Discourse on the Origin of Inequality Among Men. To the question, "What is the origin of the inequality among men, and is it justified by natural law?" he put forth a powerful argument that people are naturally good and that any corruption must be the result of a number of historical factors, including the idea of property ownership which necessitates governmental protection; this time, however, the academy judges deemed his essay too long and nonstandard and did not award him the prize. In the intervening years, Rousseau had written an opera, Le Devin du Village, which was a success. He published a novel, Julie or the New Heloise, several years later; it became very popular as well.

In 1762 came his seminal philosophical works: The Social Contract, on political philosophy, and Emile, on education. In the former, he began with the famous opening line "Man is born free, and everywhere he is in fetters" and then set out a vision of how a government could protect both the character and equality of his citizens; he also outlined an argument that the general will is most satisfied when a government acts to protect its citizens. In both works, he had unkind things to say about the Catholic Church (which he had joined some years before); threatened with punishment, he fled to Switzerland and wrote his autobiography, which was published his death as Confessions. He rejected an appeal by the equally famous philosophe Voltaire to take refuge with him. On the run again, he went to Berlin and then England, before returning to Paris, in 1770. He went back into the music business, as a copyist. He wrote two more autobiographical works, Rousseau: Judge of Jean-Jacques and Reveries of the Solitary Walker. In October 1776, he sustained injuries in an accident involving a carriage and a large dog, and his health declined. Friends reported that he had the occasional seizure after the accident. He died suddenly of a stroke, on July 3, 1778; he was 76.

|

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White