The Huguenots: French Protestants

Part 3: Extremes and Diaspora

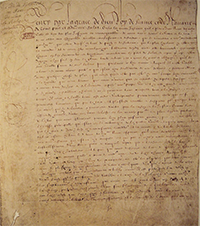

A month before, in an effort to head off the continued violence, Henry had issued the Edict of Nantes (right). This, more than any victories won by either side, precipitated the end of the Wars of Religion. In this pronouncement, Henry declared that Catholicism was the French state religion while also granting religious freedom to Protestants. Henry IV died by the hand of a Catholic assassin, in 1610. Right away, Henry's wife, Marie d'Medici, confirmed the Edict of Nantes, ostensibly to head off religious riots. Their young son, Louis, became King Louis XIII. That policy continued for a decade or so, until the king's advisor Cardinal Richelieu targeted Huguenots once again. An uprising against Catholic repression resulted in a royal crackdown, and the number of Huguenot-friendly towns decreased. A pair of new Huguenot leaders, Henri de Rohan and Benjamin de Soubise, led another revolt in the mid-1620s. Richelieu responded with great force, laying siege to the stronghold of La Rochelle for 14 months before royal troops captured it, in 1628. An agreement the following year, the Peace of Alais, reaffirmed the Huguenots' right to maintain their worship but took away all of their political rights.

Louis XIII died in 1643, and his son became Louis XIV (left). The new king maintained the terms of the 1629 Peace for a time but eventually bowed to escalating pressure from his Catholic clergy and started chipping away at Huguenots' privileges. They suddenly found it harder to join guilds. They could not establish new schools. All of those pressures disappeared if they agreed to become Catholics. The king also targeted the Huguenots' houses of worships, ordering the destruction of hundreds of churches. Many of the Huguenot faith continued to meet, in secret in the woods at times. All of these measures were unsettling to not only Huguenots but also to Catholics because of the resulting disruptions–to their daily lives, to their families, to their businesses, and to the economy as a whole. Jean-Baptiste Colbert, the finance minister, warned the king of wholesale economic disruption if he acted too strongly against the Huguenots. By this time, their numbers included a large number of tradesmen, businessmen, and otherwise important people, some of whom were very wealthy. Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes, on Oct. 18, 1785, officially in the Edict of Fontainebleau. At a stroke, the Protestant religion was outlawed. All French children had to grow up in the Catholic faith. Adult Huguenots had to convert to Catholicism or face grave persecution, including seizure of property. The revocation opened the floodgates of emigration, as hundreds of thousands of Huguenots left France, going to England, Germany, the Netherlands, South Africa, and the U.S. A large Huguenot community developed in America, giving rise to some famous early leaders, among them Paul Revere, whose father was a Huguenot immigrant, and George Washington, who had Huguenot lineage in his maternal lineage. The Huguenot religion in France existed only in the shadows for just more than a century. King Louis XVI, on Nov. 7, 1787, issued the Edict of Tolerance, which gave back to the Huguenots their right to practice their religion within French borders. Two years later, in the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizens, Huguenots stood with other Protestants and with Catholics as having equal rights under the law. First page > Early Days and Freedoms > Page 1, 2, 3 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White