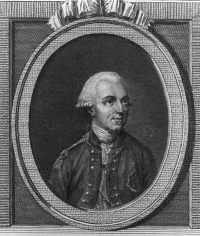

Sir Henry Clinton: Redcoat Commander

Sir Henry Clinton was a dedicated soldier who was commander-in-chief of British Army forces in North America during the Revolutionary War. He enjoyed several early successes but was later blamed for how the war ended. He was born on April 16, 1730 in Newfoundland. His father, Royal Navy officer George Clinton, was Royal Governor when Henry was born. He was appointed Governor of New York in 1743, and the family moved there.

Clinton saw his first military commission in 1745, assigned to the former French fortress at Louisbourg, which English forces had captured during the War of the Austrian Succession. The treaty that ended that war gave the fortress back to France; England took it again in 1758, during the French and Indian War. Clinton fought for England in the Seven Years War, in Germany, and was named aide-de-camp to Duke Ferdinand of Brunswick. He returned to England in 1762 after being wounded. A decade later, he added a seat in Parliament to his repertoire. He had married Harriet Carter in 1767; they had five children. She died shortly after giving birth to their fifth child, and a devastated Clinton spent the next year in mourning. He never remarried. He delayed taking his seat in Parliament, instead traveling to the Balkans to study Russian army tactics; the Russo-Turkish War had just finished. Clinton joined Parliament in September 1774. In May 1775, when he had reached the rank of major general, Clinton went to Boston, as the third in command of the British forces in America. Overall command at that stage was held by Thomas Gage, and his second-in-command was Sir William Howe.

It was Clinton (center right) who sent troops to dislodge the Continental Army from atop Breed's Hill, in what has come to be known as the Battle of Bunker Hill. He also won the Battle of Long Island and directed the successful occupation of New York. Clinton chafed behind Gage and Howe, both of whom routinely ignored Clinton's suggestions, one of which was that the British should focus on capturing Continental Army commander-in-chief George Washington, rather than trying to occupy large cities full of revolutionaries. In October 1777, the British command removed Gage as commander-in-chief, replaced him with Howe, and Clinton moved up to second-in-command. Howe sent Clinton to the south the assess the military situation there; in his Clinton's absence, American troops placed a number of guns on Boston's Dorchester Heights, forcing the British to evacuate the city. During a campaign in New York in 1777, Howe took away most of Clinton's troops, forcing the latter's attempt at resignation; King George III refused and knighted Clinton instead. Howe was supposed to take those troops and march up the Hudson River Valley to meet up with General John Burgoyne. This plan never came to fruition–primarily because Howe went instead to Philadelphia–and, in fact, Burgoyne surrendered to the Continental Army at Saratoga. Clinton, who had taken the remainder of his troops and did what the plan had called for but didn't arrive in time, benefited from the defeat, achieving the rank of lieutenant general and, after Howe resigned, was named commander-in-chief.

A classically trained military man, Clinton was a realist and a forward thinker. He was not convinced that the British could win the war or that they would want to continue to occupy the 13 Colonies if they did; when France joined the war on the side of the Americans, Clinton was even more convinced that he was right. Clinton was very much in favor of a southern strategy. He had been part of a 1776 expedition that had failed to capture the city. He finally got the chance to unfold it in 1780. Before that, however, he had to send a large part of his army to the Caribbean, to the British West Indies from falling in the hands of the Americans or their new ally, the French. Clinton ordered the evacuation of Philadelphia and battled the Continental Army to a draw at the Battle of Monmouth. He set up headquarters in New York City. Clinton played a role in recruiting African-Americans to the British cause, issuing the Philipsburg Proclamation on June 30, 1779. Similar to a promise from Virginia Governor Lord Dunmore four years earlier, this proclamation declared that runaway slaves could find a home in the British Army. Hundreds did.

Clinton's preference for a southern strategy saw initial success, as first then Savannah and then Charleston fell, the latter on May 12, 1780. Clinton returned to the north, leaving General Charles Cornwallis in the charge in the south. Clinton found his northern forces thwarted by French reinforcements; at the same time, he received more and more reports of Cornwallis adopting his own strategies in the south. On hearing that Cornwallis had settled in Yorktown, Va., and issued a call for reinforcements Clinton tried valiantly to give Cornwallis what he needed. However, the French blockade by sea and a concentration of American forces on land prevented any reinforcement of the British Army at Yorktown. Cornwallis surrendered on Oct. 19, 1781, and the war was effectively over. Many in the British Government blamed Clinton for the defeat, and he did not get another commission. He ended up writing his own version of the events that resulted in American independence. He returned to Parliament and was promoted to full general in 1793. He died on Dec. 23, 1795, in Gibraltar, where he had been appointed governor. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White