The National Constituent Assembly of France

Part 2: Taking Control

The tithe abolition of August 1789 was part of the August Decrees, of which the Assembly passed a total of 19. Among the other decrees were the following dictates:

One of the prime achievements of the National Constituent Assembly was the creation of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, in August 1789. Helping draft this landmark document was the Marquis de Lafayette, who had returned after helping the United States win its independence from Great Britain. Clearly inspiring the language and intent were the words and ideas found in the American Declaration of Independence. The overarching pronouncement of this product of learned counsel was that "men are born and remain free and equal in rights." This was a direct contravention to the idea that a monarch had absolute authority over his or her subjects. Meanwhile, the women of France were having a worse time of it than the men. For all of the equality crammed into the Declaration, it didn't mention women; in fact, it specifically said men are "born free and equal." On Oct. 5, 1789, a crowd of 7,000 women gathered at markets in Paris and marched On July 14, 1790, the country marked a year since the Storming of the Bastille by celebrating the drive toward greater equality. Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand, a former clergyman who had attended the Estates-General and then sided with the Third Estate and helped write the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, led a mass on that day, during which those in attendance swore allegiance not to any deity or religious authority figure but to "the nation, the law, and the king." That gathering was one of several that took place during a handful of days. The king and royal family attended several of those gatherings. The National Constituent Assembly had continued to meet and to try to hammer out a form of government and a set of laws to enforce the August Decrees and other pronouncements made in the year since the Tennis Court Oath had jump-started the process. On June 20, 1790, the Assembly had abolished all trappings of nobility from the knighthood, adding to the number of nobles who fled the country. Keeping the peace all of these many weeks were both the National Guard, who were protecting the royal family, by summer of 1790 living in the Tuileries, and the Royal Army, who generally favored the direction that the politics of the country was heading and saw no need to intervene on behalf of either king or Assembly. One significant change to military procedures as a result of the drive toward more equality–that officers be appointed according to ability rather than nobility–convinced many existing officers to join those leaving the country. The Assembly on Oct. 31, 1790 removed all restrictions on internal trade, making free trade possible across the country. This removed another source of revenue, customs duties, on which the Crown had depended for many a year.

For some time, many leaders of the Revolution had feared that the king would try to flee the country. He did just that, on the evening of June 20, 1791. He had taken that action as a result of a secret meeting between representatives of Austria, Sardinia, Spain, and Switzerland that had resulted in a pledge of invasion in order to rescue Louis XVI from his subjects. The king refused such assistance but did accept the offer of safety at Montmédy that was extended by General Bouillé. Thus it was that king and family traveled by carriage on the road to Chãlons, toward Montmédy. The Assembly, having discovered the king's absence, announced that it had assumed executive power and encouraged the army to take an oath to defend the Assembly, not the king. Louis, meanwhile, revealed himself to his subjects at Varennes on June 21 and was arrested and returned to Paris. Also of supreme significance, a unanimous resolution of the Assembly on Sept. 4, 1791 had called for "a code of civil laws common for the entire realm." The result was the Napoleonic Code. The Assembly finally achieved what it had set out to do at the beginning, creating the Constitution of 1791. The king had agreed to become a constitutional monarch, and the Constitution had not given him much power. Having served its purpose, the Assembly met for the last time on Oct. 1, 1791. Replacing it was the Legislative Assembly. First page > Origins and Controversies > Page 1, 2 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

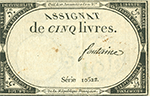

The Assembly went ahead, even to the point of creating a new currency, the assignat. Further actions against the Church included the abolition of the tithe in August 1789 and the abolition of monastic vows the following February. Whatever members of the clergy (those who had not abandoned the calling altogether and re-entered secular society) were left found themselves effectively wards of the state after the July 12, 1790, passage of the Civil Constitution of the Clergy, which, significantly, replaced the Church method of appointing bishops and priests with one of election by the people at large.

The Assembly went ahead, even to the point of creating a new currency, the assignat. Further actions against the Church included the abolition of the tithe in August 1789 and the abolition of monastic vows the following February. Whatever members of the clergy (those who had not abandoned the calling altogether and re-entered secular society) were left found themselves effectively wards of the state after the July 12, 1790, passage of the Civil Constitution of the Clergy, which, significantly, replaced the Church method of appointing bishops and priests with one of election by the people at large.

to Versailles, demanding that the king and the Assembly listen to their concerns about their plight in life. They also implored both monarch and legislative body to move to Paris, where a large population resided, rather than ensconce themselves at Versailles, far away from the still unsettling events in the capital. The women brought with them a considerable number of weapons, not only handheld ones but also a handful of cannons. Lafayette and 20,000 of the National Guard kept the peace, barely, but couldn't stop many of the crowd from storming the palace and killing a handful of guards. The next day, the king and his family agreed to move to Paris.

to Versailles, demanding that the king and the Assembly listen to their concerns about their plight in life. They also implored both monarch and legislative body to move to Paris, where a large population resided, rather than ensconce themselves at Versailles, far away from the still unsettling events in the capital. The women brought with them a considerable number of weapons, not only handheld ones but also a handful of cannons. Lafayette and 20,000 of the National Guard kept the peace, barely, but couldn't stop many of the crowd from storming the palace and killing a handful of guards. The next day, the king and his family agreed to move to Paris.