The First Battle of the Somme

The Battle of the Somme was a monthslong struggle to gain territory and advantage during World War I. It featured many of the horrors of war: artillery bombardments, machine gun battery fire, infantry advances across no man's land, and even the first deployment of tanks in battle. The number of casualties on both sides was very, very high.

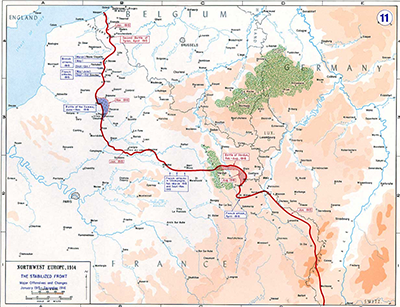

The Allied powers had met in December 1915, to plan strategy for the following year. The war commanders agreed on a solid assault all around, with Russia putting pressure on Germany and Austria-Hungary in the east and France and the United Kingdom forcing the issue in the west. Part of the latter strategy was an attack in Flanders. As the year 1916 got under way, the western Allies changed their strategy to making an attack on Picardy, along the Somme River, which would involve both French and British Expeditionary forces. The German attack on Verdun altered that strategy yet again, accelerating the timeline for the joint offensive and making British forces take the lead. As the defense of Verdun looked less and less certain, the Allies made their final preparations for the attack on the Somme. They set the date of June 24 as the day to begin.

A weeklong bombardment preceded the infantry attack. British guns ejected nearly 2 million rounds on the German positions, hoping to decimate the barbed wire, trenches, and fighting force within. That aerial assault wasn't nearly as effective as it could have been because by this time, armies' execution of trench warfare had evolved: The German armies had dug a series of underground Members of 11 divisions of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) advanced on a 15-mile front north of the Somme River. They walked slowly across no man's land, giving the defenders ample On the same day, five French divisions moved forward on an 8-mile front on the south side of the Somme. Defenses there were weaker than on the north side of the river but still formidable. Losses were great. The fighting continued, with British commanders determined to break through the German lines and, at times, German counterattacks seeking to break that rhythm. More aerial bombardments preceded more infantry attacks. More deaths followed. One British attack, on July 14, succeeded in taking Longueval Ridge, giving them a modicum of success. Such surprises were few and far between. By the end of July, British and French casualties exceeded 200,000 and German casualties exceeded 160,000. The battle went on, with morale dropping along with soldier numbers. The German strategy had been to make the Allies fight a war of attrition, and the Battle of the Somme was certainly becoming that. Further south, the French and Germans were also fighting for control of the hugely strategic Verdun. German success there turned into failure, eventually. That, coupled with a slow but steady advance by the Allied forces at the Somme convinced the German high command in late August to remove the overall leader, Erich von Falkenhayn, and replace him with Paul von Hindenburg, famous for his part in the Eastern Front victory at Tannenberg in 1914. The result was a shift in focus, with German lines falling back but only in order to achieve a position of superior defense.

The British forces deployed tanks for the first time in battle on September 15, during a attack at Flers Courcelette. Four dozen Mark I tanks rolled along with 12 divisions of infantry on that day. Many of the tanks didn't make it to the front line, but some did and the result was an overall British advance of some 1.5 miles. The price of that was 29,000 men killed, injured, missing, or captured. The battle continued. Heavy rains made battle even more treacherous in October, as the battle dragged on into November. In all, the two sides fought 12 separate battles. The final Allied advance ended on November 18, with territory taken equaling 7 miles in 141 days. Total losses are disputed, although many sources say that German losses exceeded 420,000 and that combined Allied losses exceeded 600,000. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

time to regain their gun positions and open fire. The death toll was very high. The BEF reported more than 57,000 casualties (19,000 killed in action) on that first day alone (the highest ever one-day total in the history of the British Army). One striking example along those lines was in the Pals battalions, made up of friends, relatives, and neighbors who volunteered to fight and were placed in the same division. Typical of the experience of the Pals battalions was the Accrington Pals, who on July 1 lost 584 of their force of 720. Even harder hit were the Royal Newfoundland Regiment of the Canadian Army, which had lost 90 percent of its men.

time to regain their gun positions and open fire. The death toll was very high. The BEF reported more than 57,000 casualties (19,000 killed in action) on that first day alone (the highest ever one-day total in the history of the British Army). One striking example along those lines was in the Pals battalions, made up of friends, relatives, and neighbors who volunteered to fight and were placed in the same division. Typical of the experience of the Pals battalions was the Accrington Pals, who on July 1 lost 584 of their force of 720. Even harder hit were the Royal Newfoundland Regiment of the Canadian Army, which had lost 90 percent of its men.