China's Ming Dynasty

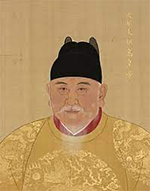

The Hongwu Emperor began the Ming Dynasty in 1368, toppling the foreign import Yuan Dynasty in the process. For nearly 300 years, Ming emperors oversaw a vast expansion in Chinese population, prestige, and influence.

The former Zhu Yuanzhang rose through the ranks of the Red Turbans and, after seeing off all challenges, on Jan. 20, 1368, proclaimed the Ming Dynasty. Having won the battles, he still needed to win the war because although Zhu was the supreme master of the Red Turbans, the rebellion had yet to overthrow their target. Zhu's army marched north and forced a recalcitrant Yuan army to retreat into Mongolia. The tables turned, now-rebel Yuan forces fought on, until in 1381 Zhu's armies succeeded in taking Yunnan and, with it, all territory once controlled by Kublai Khan and his successors. The first emperor of the Ming Dynasty set about shoring up his reign and his empire, ensuring competent government bureaucracy by continuing the Confucius-based civil service examinations that the Yuan rulers had restored. In a stark contrast to Kublai Khan's embracing of Chinese styles and traditions, the Hongwu Emperor, also named Taizu, banned Mongol clothing and names. As an extension of this, the emperor severely discouraged international trade, seeing it as a threat to Chinese ideals. Taizu much preferred to avoid getting involved in foreign conflicts and, unlike some of his predecessors, refused to take sides in an ongoing dispute in neighboring (what now is) Vietnam. At the same time, Taizu was more than willing to defend his coasts from Japanese raiders. This did not mean, however, that the emperor reduced the size of the army. He was not entirely trusting that another Mongol invasion wasn't on the horizon. When Taizu died, in 1398, he had been emperor for three decades and had presided over a period of growing prosperity and prestige. Taizu mandated that his successor be Zhu Yunwen, the oldest surviving son of Taizu's oldest son, Zhu Biao, who had died in 1392. Zhu Yunwen became the Jianwen Emperor. That ruler's reign was dominated by a struggle for supremacy. Zhu Di, a son of the Hongwu Emperor, claimed that he was the rightful heir and vowed to take the throne for himself. He was ultimately successful and declared himself the Yongle Emperor in 1402. He was one of China's most famous emperors. In order to encourage greater internal trade, the Yongle Emperor ordered an upgrade of the Grand Canal. The 1,100-mile-long waterway had its origins during the 6th Century Sui Dynasty but had fallen into disrepair.

Perhaps the most long-lasting of Chengzu's programs was the construction, between 1406 and 1420, of the Forbidden City, a huge compound of imposing buildings, halls, gardens, bridges, pagodas, and canals–all enclosed by high walls and surrounded by a wide moat.  The most visible of the emperor's initiatives might have been the voyages of Zheng He and his large fleet. On seven expansive voyages from 1405 to 1433, they sailed into the South Pacific, the Indian Ocean, the Persian Gulf, and along the east coast of Africa. In exchange for deliveries of Chinese silk and Ming porcelain, civilizations far and wide agreed to maintain the Chinese tribute system. Among the exotic elements that Zheng He and his sailors brought back home from these voyages were giraffes and theretofore unknown gems and spices. Great Wall or not, the Mongols continued to threaten, and the Yongle Emperor again found himself on campaign. It was 1424 and the fifth time that the emperor had led his army against enemy forces. It proved to be his last. He died, at 64, of illness and his oldest son, Zhu Gaochi, succeeded him, becoming the Hongxi Emperor.  A few generations later, the Zhengtong Emperor faced a supreme difficulty known as the Tumu Crisis. A Mongol army invaded in July 1449, and the emperor himself led a large force to confront the enemy, leaving the emperor's younger brother as temporary regent. The Mongol force defeated the Ming force, and the victorious Mongols claimed among their prizes the emperor himself, as a captive. When the regent claimed the throne as the Jingtai Emperor, the Mongols released the former Zhengtong Emperor and allowed him to return home. The new emperor didn't give way, however, placing his older brother and predecessor under house arrest. This situation endured for seven years, until the older brother took advantage of a severe illness inflicting his younger brother the emperor and proclaimed a coup. The former Zhengtong Emperor then became the new Ming ruler, calling himself the Tianshun Emperor. He completed the turnabout, placing his usurping younger brother under arrest; the latter died not long afterward.

The Mongol threat continued, with a raid led by Altan Khan reaching the outskirts of Beijing. In response, Ming rulers ordered a major refortification of the Great Wall. In an example of a two-pronged strategy, however, some Ming rulers also hired soldiers of Mongol descent to fight against the invaders. Some of those soldiers fought with the general Cao Qin in a coup attempt against the Tianshun Emperor; the ruler only just survived the struggle, during which some of the Forbidden City palaces burned. The Hongwu Emperor had embraced policies of isolation. His son, the Yongle Emperor, had done the reverse, punctuated supremely by the voyages of Zheng He. As the 15th Century wound down, Ming rulers and their ministers more and more embraced a return to looking within. New laws curtailed the number and size of ships. New Chinese relations with Europe were varied as well. Trade between East and West had long been established. Zheng He's voyages reinvigorated seaborne trade. By the time of the Ming Dynasty, European sea powers were more and more in waters traditionally patrolled by the powers of the East. China and Portugal, in particular, were both traders and antagonists. The same was true of China and the Netherlands; those two civilizations fought a series of conflicts in the early 17th Century. China and Spain had a relatively friendly relationship, and it was from Spain that Chinese merchants obtained New World delights like peanuts and sweet potatoes. The main Chinese exports were silk and the famed Ming porcelain. At the same time that China was struggling against Dutch interests in the South Pacific, the Chinese interior was a hotbed of famine, brought on by unusually dry and cold weather caused by the Little Ice Age. Manmade disasters occurred as well, as a gang of malcontents ripped up a number of dikes along the Yellow River, causing flooding that killed a great many people and caused a great deal of other damage as well. As had happened a few times before, widespread famine led to disillusionment with the government and, in this case, uprisings that turned violent. Aiding these were a large influx of Manchus, people from Manchuria, who had gained increasingly in numbers and placements within the Ming state itself. Pressure came from directly within, as a number of units of soldiers turned disappointment at not being shipped supplies into a grievance against their superior officers and rebelled. Li Zicheng, one of those peasant soldiers so disaffected, led a large armed force that took over Beijing in May 1644. Rather than submit, the Chongzhen Emperor took his own life. Seeing the writing on the wall, the Ming commander in the north, Wu Sangui, opened the gates of the Great Wall at Shanhai Pass, allowing a large Manchu force to pass through unhindered. The joint enemies of Ming China never quite became allies, and the more well organized Manchus seized control from Li Zicheng and his force. The result was a new dynasty, the Qing.

|

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

practices diminished the amount of trade with other civilizations. A series of raids by Japanese ships on Chinese ships and coastal communities soured relations between the civilizations. Near the end of the 16th Century, one of Japan's most powerful warlords, Hideyoshi, proclaimed that he would settle the differences by invading China. The conflict, known as the Imjin War, played out on the Korean Peninsula; although China was victorious, the losses in lives and money were large.

practices diminished the amount of trade with other civilizations. A series of raids by Japanese ships on Chinese ships and coastal communities soured relations between the civilizations. Near the end of the 16th Century, one of Japan's most powerful warlords, Hideyoshi, proclaimed that he would settle the differences by invading China. The conflict, known as the Imjin War, played out on the Korean Peninsula; although China was victorious, the losses in lives and money were large.