The Aztec Calendar System

The Aztecs, who dominated Mesoamerica for more than two centuries during the late Middle Ages, had a sophisticated system of keeping track of the days. In fact, they had two calendars, which reconciled relatively regularly.

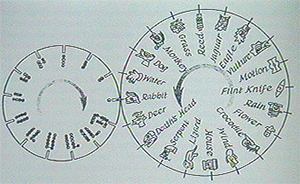

The 365-day calendar, or xiuhpohualli, was known as the agricultural calendar because the Aztecs based it on the progress of the Sun. A solar year was a xihuiti; a day was a tonalli. This calendar had "months" (veintena) that contained 20 days, each of which had its own symbol. The year had 18 of those months, and the remainder was five days (nemontemi), which occurred as a bloc at the end of the calendar year and had no associated symbols. Each of those 20-day groupings had a name:

The other calendar, the tonalpohualli, had 260 days and tracked religious ceremonies. Each day on this calendar was a combination of a number from 1 to 13. After 20 repetitions of that 13-day set (called a trecena), the calendar turned over. Each of those 20 trecenas had its own associated number, name, symbol, and god/goddess.

The two calendars joined up every 52 years. It was common practice to offer sacrifices to the gods at this time.  The Aztec sun stone, a representation of these calendars, dates to the early 16th Century. The massive stone (measuring more than 11 feet in diameter, more than 3 feet thick, and weighing more than 54,000 pounds) disappeared after the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire; workers doing repair work on Mexico City Cathedral found the stone again in 1790 and were directed to affix it to a wall of the cathedral. There it stayed until 1855, when it gained a new home, the Archaeological Museum. The stone reached its current home, the National Museum of Anthropology and History, in 1964.

|

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White