The Assyrian Empire

Part 2: Imperial Highs and Lows

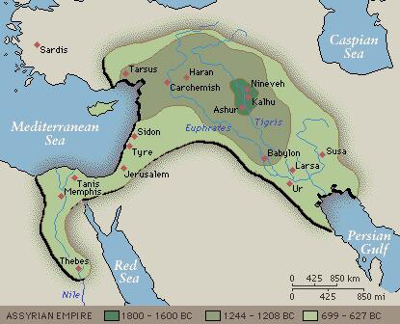

Subsequent kings continued the expansion of the empire's borders, engineering siege campaigns that would routinely end badly for the city being besieged. The Assyrians made a specialty out of siege weapons, their favorites being massive and tall wooden towers with battering rams at the bottom and wheels underneath. One ruler who saw more than conquest as the goals of a military campaign was Ashurnasirpal II (on the throne 884–859 B.C.), who, anticipating Alexander the Great a few centuries later, took with him men whose job it was to catalog the animals and plants that they found on campaign; the king was the first to compile an empirewide list of such things. He also moved the capital, to Calah.  A century later came one of the most successful kings of the Assyrian Empire, Tiglath Pileser III. Under his leadership, the Assyrian army reached its peak effectiveness. He reorganized the military and the bureaucratic mechanisms that helped it function, instituting the kinds of training and tactics study that would be standard issue for military leaders in much later times. He also standardized Aramaic as the official language of the empire. To this end, he had translated a significant number of documents from Akkadian into Aramaic and also ordered royal scribes and other writers to make use of the newer, more widely spoken language.

A subsequent king, Sargon II, brought the empire to its greatest geographical extent, vanquishing the perennial enemy Uratu in 714 B.C. Next on the throne was Sennacherib, who listed on his conquest list none other than Israel and Judah, including the sacking of Jerusalem. He moved the imperial capital to Nineveh and built a new and very large and extravagant royal palace. He embarked on a beautification campaign in the city, including a set of gardens that bore a striking resemblance to the Hanging Gardens of Babylon. He brought to the conquest of Babylon the same ruthlessness that he had used on Israel and Judah and ordered the temples looted. For that, he suffered the same fate as his predecessor who had done the same thing. His own sons killed him, and one of those sons, Esarhaddon, took the throne and had Babylon rebuilt. This king succeeded where his father had not, in conquering Egypt and then drove further south into Africa, to Nubia, which today is Sudan. When Esarhaddon died in 668 B.C., he gave way to a ruler who was perhaps the most learned ever to sit on the Assyrian throne: Ashurbanipal.  He was on the throne for 41 years and exhibited a cruel streak in waging war on his enemies, taking particular satisfaction in subjugating the Elamites, a longtime enemy. He also, however, was fond of knowledge and ordered a great campaign of information collection. He sent royal representatives out into the empire, to visit towns and cities and other kinds of settlements, in order to bring back originals and copies of scrolls and books from his subjects. The result was the famed Library of Ashurbanipal, one of the greatest libraries of antiquity. This collection of texts numbered 1,200 in all. Ashurbanipal himself was a very learned man, adept at mathematics and able to read and write; he contributed several of his own writings to the library. A copy of the Epic of Gilgamesh was found in Ashurbanipal's library, as was a long list of ancient rulers. The sheer number of tablets found in the library proved helpful in deciphering cuneiform. Ashurbanipal died in 627 B.C. The Assyrian Empire did not recover. Its neighbors the Babylonians and the Medes got together and sacked Nineveh in 612 B.C., tearing down not only the royal palace but also the Library of Ashurbanipal. Ironically, the fire that resulted preserved the clay tablets that made up the Library's contents by baking them and then burying them. They were lost to the conquerors but preserved for posterity; the tablets were discover many years later, intact. Babylon reigned supreme again in the ancient lands of Mesopotamia. The territory once ruled by a long series of Assyrian kings came under the umbrella of another uniting ruler 60 years later; his name was Cyrus the Great. First page> Growing into Power > Page 1, 2 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

The next significant monarch in Assyria's history was Tiglath Pileser I, who gained the throne in 1115 B.C. and kept it for three decades. He was a very successful military campaigner, extending the empire's borders as far west as the Mediterranean Sea. He was a well-rounded figure, championing the use of greenery in the forms of gardens and parks in the empire's big cities. A scholar himself, he collected cuneiform tablets on a host of subjects and wrote a set of royal annals. For his tablet collection he had built a library; for himself he had built a new palace. This king, also, found himself in a class by himself in terms of influence, his successors not proving up to the challenge of maintaining stability. Again, civil war reigned. Two centuries later, another strong hand emerged. Adad Nirari II ruled the empire from 912 B.C. to 891 B.C. and brought peace and a border expansion the likes of which hadn't been seen in a while. Babylon in the intervening years had wrested itself free. Adad Nirari II reconquered it and avoided the mistake that Tukulti-Ninurta I had made, ordering the temples to remain untouched; further, this new conqueror left the Babylonian king on his throne and kept the peace by initiating a treaty between the ancient city and the ascendant empire.

The next significant monarch in Assyria's history was Tiglath Pileser I, who gained the throne in 1115 B.C. and kept it for three decades. He was a very successful military campaigner, extending the empire's borders as far west as the Mediterranean Sea. He was a well-rounded figure, championing the use of greenery in the forms of gardens and parks in the empire's big cities. A scholar himself, he collected cuneiform tablets on a host of subjects and wrote a set of royal annals. For his tablet collection he had built a library; for himself he had built a new palace. This king, also, found himself in a class by himself in terms of influence, his successors not proving up to the challenge of maintaining stability. Again, civil war reigned. Two centuries later, another strong hand emerged. Adad Nirari II ruled the empire from 912 B.C. to 891 B.C. and brought peace and a border expansion the likes of which hadn't been seen in a while. Babylon in the intervening years had wrested itself free. Adad Nirari II reconquered it and avoided the mistake that Tukulti-Ninurta I had made, ordering the temples to remain untouched; further, this new conqueror left the Babylonian king on his throne and kept the peace by initiating a treaty between the ancient city and the ascendant empire.