Religion in Ancient Egypt

Part 3: Death and the Afterlife A powerful concept within the pantheon of Egyptian religious beliefs was the idea of rebirth or re-emergence. The Egyptians saw this idea in concepts small and large. Every day, the sun god, Ra, made his journey across the sky and then was in hiding during darkness, overcoming a struggle with Apep, the serpent god, who represented chaos; on the next day, Ra repeated the cycle. As well, the Nile River, on which the Egyptians depended for their daily water needs, flooded every year, bathing the nearby soil with replenishing nutrients and providing a longer cycle of rebirth.

The Egyptian belief system included a complicated system of ideas and practices associated with death and what came afterward. The Egyptians believed wholeheartedly in the idea of human rebirth, as personified by the god Osiris, who had done just that, rising beyond being murdered by his brother Seth to exist again, thanks to the efforts of his wife, the goddess Isis. Osiris was regarded as the mythological first king of Egypt and the god who brought civilization to its people.

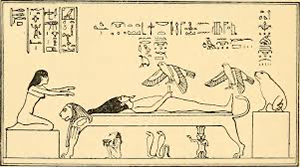

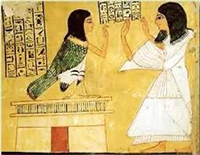

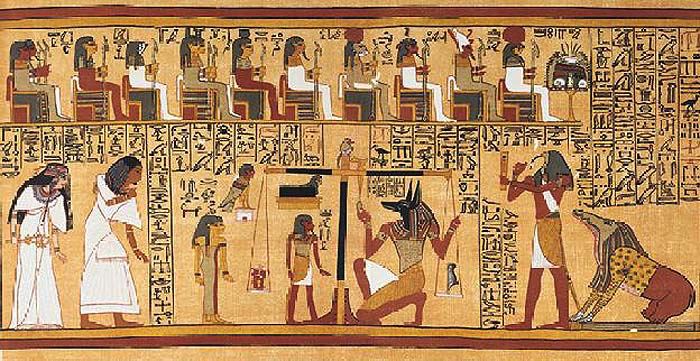

The Egyptian people believed that a certain part of a person, known as the ka, could exist after death. The people generally thought of the ka as the life force, and some sources see this as as the equivalent of the modern concept of the soul. When a person died, the Egyptians believed, the ka left the body. In the same way that while a person lived, that person sustained himself or herself, along with his/her ka, with food and drink, the Egyptians believed that they needed to provide food and drink for the ka after a person died. This is why so many Egyptian tombs have been found to include evidence of having once contained fresh food and drink. In the same vein, the Egyptians believed that each person had as well something called the ba, or a combination of characteristics that made that person unique. When a person died, the Egyptians believed, the ba remained with the body and it was, therefore, necessary to perform a set routine of rituals in order to help convince the ba to leave the body and join the ka; this union was referred to as an akh. A complication to this, the Egyptians believed, was that the ba returned to the body each night, staying with the body during the hours of darkness; the people, therefore, thought it important to keep the body in some form of good shape in order to continue to be able to receive the ba. This is one reason that the Egyptians adopted the practice of embalming. In the early days, the Egyptians believed that only the pharaoh had a ba and that he alone had the power to become one with the gods after death. As time went on, people believed more and more that this possibility was open to everyone. However, one had to fulfill certain conditions, one of which was to wait for a time in the Duat, a sort of nothingness that preceded a person's going on to the afterlife. (Ra, the sun god, passed through this mysterious region every night on his daily journey through the sky.) The priests developed the idea of the "Weighing of the Heart," in which a person who died could live on, in a manner of speaking, in the afterlife provided that his or her heart was judged to be light.

The priests developed an elaborate procedure for this sort of judgment. Osiris, the god of the underworld, presided over the "weighing," which took place in the Hall of Truth. A host of 42 other gods–including Thoth, the god of wisdom–did the judging. Anubis weighed the heart against the white feather of truth, from the headdress of Ma'at, the goddess of truth and justice. The god Thoth recorded the results of the weigh-in. If the heart was heavy, the soul-eater Ammut (Amemet) would devour it, preventing the person from taking part in the afterlife. The goal was to have a light heart, the same weight as the feather (or lighter); and the way to have a light heart was to do good deeds. The overall goal was to live without pain in the Fields of Yalu (or the Field of Reeds). The final task before gaining that state of persistence was to be kind to the Hraf-haf, a creature who inhabits the boat in which the person is rowed across the Lily Lake (or Lake of Flowers) to the final Field(s). Those not kind enough to this creature did not gain passage across the lake. Mummification

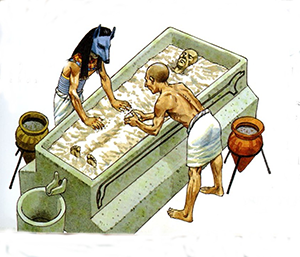

The most expensive service involved the most attention to the various parts of the body and the use of the most expensive purification substances. Embalmers removed the entirety of the abdomen and cleaned and washed what remained, with palm wine and then with ground spieces; the last step in this part of the process was to fill the cavity with cassis, myrrh, and other aromatic substances and then sew the abdomen shut. As for the brain, embalmers used an iron hook to remove the deceased's brain through the nose. The next step was to place the body entirely in natron, a chemical salt, and leave it thus covered for 70 days, so the natron would dry out the body. Embalmers then filled the body cavity with dry materials like leaves and sawdust, so the body looked lifelike. (In the latter part of Egyptian civilization, embalmers took to returning the organs to the body.) The last step was to wash the body and then wrap it in linen, treated with gum that it would stick to the body. Embalmers then handed the body back to the family, who placed it in a wooden coffin for burial. A family who could afford a slightly less costly process opted for the mid-range solution, which involved not an incision or a removal of organs but an injection of oil of cedar and then a curing in natron, as with the expensive option, again for 70 days. During that time, the oil of cedar and natron have dissolved much of the body's interior. What is left, skin and bones, is returned to the family for burial. The least expensive option skipped the oil of cedar injection and involved a simple wash-out of the intestines and a removal of all internal organs except the heart; the organs were then placed in canopic jars. In both this option and the mid-range option, the family provided their own linen for wrapping the body. The Egyptians also had this kind of treatment performed on their pet baboons, birds, cats, dogs, and even fish. After all of this embalming and purification had occurred, the family had a funeral, which was generally public. Those who could afford such things hired professional mourners known as the Kites of Nephthys.

The size and contents of a person's tomb depended almost entirely on how much money was remaining after the body preparation. The more money a family had, the larger a tomb could be and the more grave goods would be placed inside. The inclusion of food and drink was common, as was the placement of shabti dolls, tiny humanlike figures that would, in the afterlife, do the tasks that the person in whose tomb they resided had been assigned. Families also included common personal items such as clothing, combs, jewelry, and favorite objects. Families who could not afford a tomb settled for a cemetery grave. First page > Gods and Goddesses > Page 1, 2, 3

|

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White