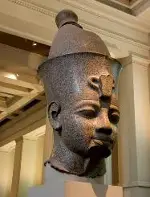

The Egyptian Pharaoh Amenhotep III

Amenhotep III was a king of Ancient Egypt at a time when the civilization was at its zenith. He made it even richer and more powerful.

Born in 1388 B.C., he was the son of Tuthmosis IV and became king at age 12. That was when his father died, and he was still too young in his own right so his mother, Mutemwia, served as regent. Amenhotep III came into his own and chose as his royal wife Tiy. Amenhotep III ruled for nearly 40 years and had a mainly peaceful reign. His great-grandfather, Thutmose III, had extended the boundaries of Egypt to their largest extent and provided a largely peaceful reign for his son and grandson. Sources talk of a rebellion in Nubia, to the south, and that the pharaoh himself led the Egyptian armies in a quelling of the rebellion. But the king is not known to have taken part in other military expeditions.

Amenhotep III proved himself a successful diplomat, maintaining good relations with his neighbors through, above all, the use of wise words. The Amarna Letters, a collection of tablets discovered in 1887, show evidence of this. He also agreed to marry more than one foreign princess in order to cement an alliance with a neighboring civilization; at the same time, he refused to send any Egyptian women to marry foreign rulers. Because of the relative peace during his reign, Amenhotep III presided over a number of years of construction of great buildings and art works. At the same time, the royal coffers continued to overflow with revenues from trade and with gold from local mines. As well, the harvests during his reign proved One thing that Amenhotep III changed radically was the temple complex at Karnak. He ordered existing monumental temples upgraded and new pylons added, pulled down temple only to put up another, called for a new entrance to an existing temple to the goddess Mut and 600 statues of the goddess Sekhmet installed around it, and directed built a new shrine to the goddess Ma'at. To that goddess he had built a new temple at Luxor as well.

Amenhotep III is far and away the pharaoh of whom the most statues survive. Archaeologists have found more than 250. He is perhaps most well-known among statuary circles for the Colossi of Memnon (above),

He directed all of this building from Malkata, his very large and ornate West Bank palace, which was augmented by a purpose-built harbor. He also presided over and encouraged a movement into sculpture that depicted its subjects in a more lifelike way than before. Appropriation of his statues by subsequent pharaohs, who replaced his name with their own, was not uncommon. He is also known for the many royal commemorative scarabs that described his accomplishments. One group of people that the king could not conyrol were the priests of the temple of Amen-Re. The king gave large amounts of money to the beautification of the temples and its surroundings and to the priests who did the upkeep; still, they proclaimed that they alone were the ones to know the will of the god. Determined to be the lord over all, Amenhotep proclaimed that he would worship another god, Aten, the sun god. Amenhotep III, who was known to have suffered severe health problems in his last years, died in 1354 B.C. and was buried in an extravagant tomb in the Valley of the Kings. His mortuary temple was one of the finest ever built. Next on the throne of Egypt was Amenhotep IV, who later became Akhenaten. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

remarkably abundant. Improvements in roads and trade routes only served to increase Egypt's wealth.

remarkably abundant. Improvements in roads and trade routes only served to increase Egypt's wealth. two giant statues that depict him and Queen Tiy. (The statue of Tiy actually depicts Amenhotep's mother, Mutemwiya, as well.) The royal couple, along with three of their daughters, formed the basis for another large limestone statue, at Medinet Habu. Queen Tiy was also the sole subject of several well-known statues. She had a very special status and was often depicted of an equal height or an equal footing with the king. An adept administrator, she more than filled the king's shoes in running the kingdom and the royal household while he was away.

two giant statues that depict him and Queen Tiy. (The statue of Tiy actually depicts Amenhotep's mother, Mutemwiya, as well.) The royal couple, along with three of their daughters, formed the basis for another large limestone statue, at Medinet Habu. Queen Tiy was also the sole subject of several well-known statues. She had a very special status and was often depicted of an equal height or an equal footing with the king. An adept administrator, she more than filled the king's shoes in running the kingdom and the royal household while he was away.