The Spanish-American War

The Spanish-American War was a military clash between two countries with competing visions of expansion. A four-month struggle, it resulted in a further disappearance of Spanish influence in the Western Hemisphere and a wider influence for the United States in both the Caribbean and the Pacific. Spain's empire-building began in the Middle Ages, with an expansion of colonization and religious conversion that focused mainly on South America but also in the Caribbean and in a part of what is now the southeastern and southwestern United States. A series of revolutions in the early 19th Century left Spain with a shrinking sphere of influence. As the 19th Century was ending, Spain had a hand in the running of Cuba and Puerto Rico in the Caribbean, the Philippines and Guam in the Pacific, and a host of other minor islands.

Many in the U.S. had long advocated taking a more active role in Cuba. At one point, many in America were advocating the takeover, militarily or economically, of the Caribbean island nation. Cuba still sold a lot of sugar to other countries, including the U.S. An 1894 American tariff on sugar angered the governments of both Cuba and Spain. Opposition forces, meanwhile, were doing what they could to disrupt Cuba's lucrative sugar trade. As a result, many in the U.S. sought stability in Cuba. On February 15, 1898, the USS Maine exploded in Havana harbor, killing 266 American sailors. An initial U.S. Navy investigation concluded that the cause was an external source, presumably a mine in the harbor. Anger across America was great, and many people believed the story beginning to circulate that Spain was behind the explosion. New York newspaper publishers William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer took the About the same time, in the Pacific, the people of the Philippines were engaged in an uprising against the Spanish-influenced government there. Sentiment for the Filipino rebels, who said that they were seeking democratic rule, was high in America. When war broke out, in April 1898, fighting took place in Cuba and in the Philippines. Spain had rejected a call from the U.S. Government to give up Cuba altogether; in response, Spain declared war. The American declaration of war followed soon after, and the struggle began. Neither country had a top-notch military at the time. Spain's armed forces had been in decline for many years and were stretched thin as well. American forces were still recovering from the devastating Civil War, which had ended just 30 years earlier. Nonetheless, both countries could put armies in the field and navies in the water. The warring forces weren't all that dissimilar in terms of numbers, but the results of the battles fought suggested a greater strength on the American side. The first battle of the war was on May 1 in the Philippines, where American ships under Commodore George Dewey soundly defeated a Spanish force and, as a result, gained control of Manila Bay. An American occupation of the Philippines was quickly under way (with a force of 11,000 ground troops), and the capture of the city of Manila itself took place on August 13. In between the Battle of Manila Bay and the capture of Manila City, another American fleet was scoring a victory, this one in nearby Guam. The Spanish presence on the small island was minimal, and the presence of an American fleet was enough to convince the Spanish commander there to surrender. In Cuba, meanwhile, fighting was fierce. Theodore Roosevelt, who as Assistant Secretary of the Navy had built up the naval presence, advocated an invasion of Cuba. As a result, he helped form an all-volunteer regiment, the 1st U.S. Volunteer Cavalry, which came to be known as the "Rough Riders." Roosevelt, an adventuresome sort, soon joined the outfit himself.

American troops advanced on an even more heavily defended Santiago, where they formed into a siege strategy that eventually succeeded in the capture of Cuba's second-largest city. Meanwhile, American naval forces moved into Guantanamo Bay, where they scored a decisive victory over the Spanish Caribbean Squadron. Most American forces began to leave Cuba, however, because they had encountered an even more deadly opponent than the Spanish: yellow fever. At one point, up to three-quarters of the American occupation force had contracted the deadly disease. The island was firmly in American hands, however, and so the next orders were for evacuation, with a skeleton crew left behind. Meanwhile, in tiny Puerto Rico, the fighting was fierce as well. An initial American blockade of San Juan Bay gave U.S. forces a decided advantage, and the invasion force eventually succeeded in capturing the capital, on August 9. Three days later, Spain called for peace. American dead from the war numbered a few thousand, with nearly two-thirds of those caused by disease. Spanish dead numbered much more, on both counts. A final treaty, yet another one named the Treaty of Paris, was signed on December 10. (The Senate ratified the treaty on February 6, 1899.) Spain gave up claims to Cuba, Philippines, Guam, and Puerto Rico. As a result, America flexed its political and military muscle in the Caribbean but also in the Pacific. By contrast, Spain's overseas holdings were reduced to a tiny percentage of what they once were. The war also served somewhat to mend some of the wounds rubbed raw by the Civil War, by giving all Americans a common enemy. One of the most famous war heroes was Theodore Roosevelt, who parlayed his popularity and his larger-than-life personality into a political career, which lasted for several decades. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

In the 1890s in Cuba, a group of guerrilla fighters led by Jose Marti revitalized a protest movement against the Spanish-led government that had flared up a few decades before. Marti had enough support to form a U.S.-based political party, the Cuban Revolutionary Party, and to get the military struggle started. He was killed, however, early on the fighting. When the Cuban Government declared martial law in 1896, U.S. President

In the 1890s in Cuba, a group of guerrilla fighters led by Jose Marti revitalized a protest movement against the Spanish-led government that had flared up a few decades before. Marti had enough support to form a U.S.-based political party, the Cuban Revolutionary Party, and to get the military struggle started. He was killed, however, early on the fighting. When the Cuban Government declared martial law in 1896, U.S. President  opportunity to blame Spain for the explosion and did so in print, in huge, bold headlines. Historians of today look back on the articles written in the New York Journal (Hearst) and the New York World (Pulitzer) as propaganda, with many unproven allegations. At the time, however, those two papers were among the most influential in the country and the resulting swell of public opinion against Spain resulted in a movement toward support of war.

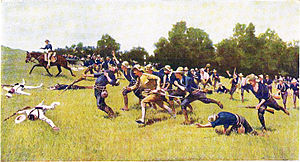

opportunity to blame Spain for the explosion and did so in print, in huge, bold headlines. Historians of today look back on the articles written in the New York Journal (Hearst) and the New York World (Pulitzer) as propaganda, with many unproven allegations. At the time, however, those two papers were among the most influential in the country and the resulting swell of public opinion against Spain resulted in a movement toward support of war. American forces landed in Cuba in late June and hooked up with Cuban rebel forces. The first battle on Cuban soil, the Battle of Las Guasimas, ended in a tactical draw, although Spanish forces left the area to shore up the defenses around Santiago. The next battles were a bit more decisive for the American effort. At El Caney and San Juan Hill, Roosevelt's "Rough Riders" and other American forces scored victories over the entrenched Spanish.

American forces landed in Cuba in late June and hooked up with Cuban rebel forces. The first battle on Cuban soil, the Battle of Las Guasimas, ended in a tactical draw, although Spanish forces left the area to shore up the defenses around Santiago. The next battles were a bit more decisive for the American effort. At El Caney and San Juan Hill, Roosevelt's "Rough Riders" and other American forces scored victories over the entrenched Spanish.