Slavery in America

The popular depiction of a slave owner was a rich person, usually a man, who owned a plantation on which grew crops, fruits, vegetables, and animals. A large number of slaves who lived on plantations worked the fields, picking cotton or other crops and otherwise tending to the fields and everything that went along with growing a crop: digging ditches, ploughing, sowing crops, cutting and hauling wood, repairing tools and machines. Indeed, some slaves were or became quite skilled in blacksmithing, carpentry, and mechanics. Outdoor slaves who did not work in the fields tended fruit and vegetable gardens. Other plantation slaves tended to more domestic tasks, such as cooking, sewing, spinning, and weaving. Many female slaves looked after the children of plantation owners.

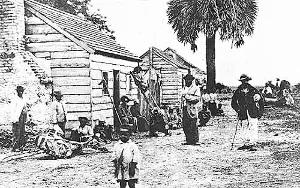

The owners of plantations lived in stately, sometimes luxurious quarters, usually a large house or collection of houses. Tending to the needs of the owner and family were household slaves. Slaves, by and large, lived in slave quarters, which were separate buildings, usually poorly constructed wooden huts, that had very little of the trappings of the plantation mansion. Living spaces were crude and crowded, with sanitation at a minimum. Illness was almost never a cause for being excused from work. This combination of factors, along with inadequate nutrition, led to many slave deaths. Particularly deadly to slaves were conditions on rice plantations. Forced workers in such places had to stand in water for hours at a time, in at times unbearable heat. Malaria was an effective killer on rice plantations, especially of young slaves. Conditions were harsh on other plantations as well. Plantations certainly employed a great many slaves, but the majority of those enslaved in North America worked in domestic settings–in houses, on small farms, and in small businesses. Slave codes At various times, throughout the history of the country until the end of the Civil War, states and even the federal government had laws that countenanced and reinforced the idea that slaves were property and did not have rights as non-slaves did. These laws varied from state to state and went through various cycles of adaptation and repeal. In their entirety, these laws are often referred to as Slave Codes. A part of a South Carolina law put it very succinctly: "The slave, being personal chattel, is at all times liable to be sold absolutely, or mortgaged or leased, at the will of his master." Slave codes and laws actively denied most rights to slaves and stipulated strict punishments for lawbreakers that could be doled out with immunity by slaveowners. Every one of the 13 Colonies eventually had slave laws on the books. New York's were some of the strictest. Slavery was more common in Southern states but was prevalent in the North as well, at least early in the history of the country. All of America's original 13 Colonies, with the exception of Georgia, allowed slavery initially. One by one, though, Northern states abolished slavery; Southern states did not. As new Southern states Alabama, Arkansas, Mississippi, Tennessee, and Texas joined the Union, they adopted variations on earlier states' slave codes and laws. Some of those codes required slaveowners to serve on patrols that roamed the countryside, searching for escaped slaves. Taking action Some slaves committed acts of passive disobedience, such as feigning illness or unassumingly sabotaging crops, machinery, or operations; others preferred active disobedience, such as refusing to work or otherwise follow orders. Punishments for all of these acts of aggression or resistance to authority were harsh, often resulting severe injury or death.

Another way in which slaves tried to change their fates was to take up arms against their owners. Some rebelled individually or in small groups, with varying degrees of success. Others gathered in larger groups, as many as several hundred. Nat Turner is perhaps the most famous name associated with slave-led rebellions. Denmark Vesey and Gabriel Prosser were others. None of them succeeded. Their stories were inspiration for other slaves to try to escape, to try to fight back in any way they could, to try to hold out against oppression, to try to hold on in the hope that something better would come along. Another form of escape for many African-Americans was a return to Africa. This was attractive to some, both born free and recently free, and the dream of some who who were still enslaved. However, the majority of African-Americans wanted to be treated fairly in America itself. In the early 19th Century, a group of prominent European-Americans formed the American Colonization Society, with the goal of transporting free African-Americans to West Africa. The society achieved a primary goal with the establishment of the Liberia colony in 1822. Many prominent European-Americans gave time and money in support of this society. Many others opposed the society and its goals. Among those speaking out against the ACS were the well-known white abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison and noted African-Americans Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

Trying to escape was one way that slaves took matters into their hands. If they were caught, they faced severe punishment; if they found their way to freedom, they sometimes felt guilt for leaving behind loved ones, friends, and those in pain and suffering. Various laws, at both the state and the federal level, provided mechanisms that protected a slave owner's right to "own" slaves as "property." Congress, first in 1793 and again in 1850, passed Fugitive Slave Laws that made aiding and abetting the escape of slaves a federal offense. Acting in their own slant on civil disobedience, abolitionists helped runaway slaves form the

Trying to escape was one way that slaves took matters into their hands. If they were caught, they faced severe punishment; if they found their way to freedom, they sometimes felt guilt for leaving behind loved ones, friends, and those in pain and suffering. Various laws, at both the state and the federal level, provided mechanisms that protected a slave owner's right to "own" slaves as "property." Congress, first in 1793 and again in 1850, passed Fugitive Slave Laws that made aiding and abetting the escape of slaves a federal offense. Acting in their own slant on civil disobedience, abolitionists helped runaway slaves form the