Shays's Rebellion

Shays's Rebellion was the first armed uprising in the new United States. It was named for Daniel Shays, one of many farmers protesting taxes and high levels of debt.

Shays, a former captain in the Continental Army, was one of the leaders of a large group of farmers (most ex-soldiers like Shays) in western Massachusetts who spoke out against their current economic situation by having public meetings and imploring their state government to enable some form of debt relief. When they didn't get what they wanted, they took up arms and took over the Court of Common Pleas in Northampton on Aug. 29, 1786. This was the start of what has come to be known as Shays's Rebellion. Many of those who fought in the Continental Army received little compensation for their service. When the war ended, many veterans struggled economically. They were used to buying things on credit or paying through barter and so had no paper money and little gold or silver. This was not a problem for those in money-making professions like banking and shipping. The farmers in western Massachusetts, however, had only their land and its farm capabilities as assets. The Massachusetts state government looked to recoup its debts by taxing its residents. Also, state businesses started demanding immediate repayment of debts, rather than give farmers and others in debt time to repay, as had been the custom in the past. These demands were partly in response to similar restrictions put in place by European creditors, following England's defeat in the Revolutionary War. State authorities began foreclosing on the farms, seizing the land and, in some cases, arresting the farmers who owed money. The farmers' first response to these actions was a peaceful one. In summer 1786, a group of farmers drafted a document of grievances and also offered suggestions for how the state government could reform the debt collection system.

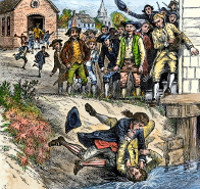

This did not go over too well with state authorities, and some farmers took more physical action. Captain Joseph Hines and several hundred other men blocked judges from entering the courthouse in Northampton. A similar action took place in Worcester. Protesters in Groton physically refused to allow the visit of a tax collector. In other cases, protesters assault tax collectors and threatened state authorities sent out to arrest them. The state legislature responded by offering amnesty to farmers who left off protesting at state courts, as long as those farmers took oaths of allegiance to the state government. At the same time, the legislature passed a law providing for harsh punishments for farmers in custody for protesting their situation while at the same time offering amnesty for sheriffs who killed any protesters. A later bill suspended the write of habeas corpus for a time, meaning that those arrested could be held indefinitely. In December 1786, a group of state militiamen was sent out to confront a farmer in Groton and, in arresting the farmer, the members of the militia seriously injured him. One of the men who took part in the Northampton court blockade was Daniel Shays, who had fought at the Battles of Lexington and Concord, the Battle of Bunker Hill, and the Battle of Saratoga. Shays led a group of 600 men in shutdown action at the court in Springfield.

In January 1787, Shays and about 1,200 other farmers marched to the federal arsenal in Springfield. Some of the farmers had weapons already, including clubs and guns and pitchforks. Their goal was to procure guns and other weapons from the Springfield arsenal, which was occupied by state militia leader William Shepard (himself a Revolutionary War veteran who had survived the winter at Valley Forge) and a few hundred militiamen. Two other groups, totaling another 1,000 men, marched in support of Shays. Leading one of these groups was another Revolutionary War veteran, Captain Luke Day, who had fought with Shays at Saratoga and also was at Yorktown to see the surrender of the English Army there. Massachusetts Gov. James Bowdoin responded to force with force, sending a group of soldiers to disperse Shays and his group. More than 4,000 armed men under the command of Revolutionary War General Benjamin Lincoln marched out to confront the farmers. On January 25, the state troops fired warning shots at Shays and the other farmers. When they didn't disperse, they fell victim to further fire, which killed a handful of farmers. They called off their march on the Springfield arsenal and retreated to nearby Chicopee. Lincoln deployed forces up the Connecticut River to prevent further retreat, and Shays and his group fled to Petersham. Lincoln followed, and Shays and others left the state, fleeing to neighboring Vermont. Shays's Rebellion was over. Shays and others found a sympathetic ear in Vermont, in the person of Revolutionary War hero Ethan Allen. He agreed to provide for their safety but refused to take up arms with them. The rebellion carried on for a few weeks, ending with a last violent confrontation in Stockbridge, won by the state militia on Feb. 27, 1787. The state legislature then passed the Disqualification Act, banning those who had taken up arms against the state government from voting, holding public office, servings on juries, or even working as schoolmasters or innkeepers. That prohibition lasted three years. In the meantime, however, Massachusetts had a new governor, John Hancock, who pardoned many who had taken part in the rebellion, including Shays and Day. Two farmers who marched with Shays were hanged. Shays returned to Massachusetts briefly but then lived out his life in Sparta, N.Y. A total of nine people died during Shays's Rebellion. Six were farmers who took up arms; three were members of the state militia called out to oppose the farmers. Massachusetts was not the only state in which such discontent was evident. Farmers in Connecticut, Maine, New York, and Pennsylvania took similar actions, although theirs did not include taking up arms. The rebellion illustrated the inability of the current federal government, under the Articles of Confederation, to deal with such a situation. No federal funds were available or allocated to finance a federal military response, so the troops who put down Shays's Rebellion were either Massachusetts state militia or mercenaries paid privately. This and other episodes led to the actions at the Constitutional Convention that resulted in the repeal of the Articles of Confederation and the eventual embracing of a new strong federal government as described in the Constitution. |

|