The Pullman Strike of 1894

The United States economy entered a severe depression in the early 1890s. Conditions were so bad economically that they led to the Panic of 1893, which culminated in a run on gold, a huge stock sell-off, and a series of bank failures. Also failing at that time were three of the nation’s largest railroads. Grover Cleveland had been elected President (again) in 1892, and by the time he was inaugurated on March 4 of that year, things were dire economically.

One of the main features for which the Pullman Company was known was its sleeper berths. An upper berth folded up during the day; passengers could fold down the upper berth at night and, including the two facing seats, approximate a bed on which to sleep through the night. Curtains hung in berths, to provide sleepers with privacy. An added measure of comfort was washrooms at each end of each rail car. Pullman employed a large number of African-American workers. A great many of these were porters, but African-Americans featured in other jobs for Pullman as well.

Pullman owned the buildings and chose the town’s leaders. He also set the rates for rent and utility payments. In the wake of the Panic of 1893, Pullman faced a drop in demand for his rail cars. One of his responses was to reduce the amount of money that he paid his employees. Wage cuts were as severe as 30 percent. At the same time, however, Pullman did not reduce rents or cut other housing-associated costs. As a result, many of Pullman’s workers (many of whom were already working 16-hour days) felt a severe economic squeeze, probably more than did Pullman himself. A delegation of workers asked Pullman for a meeting to discuss their concerns, but Pullman refused to meet with them. He also hired other people to do the work.

On May 11, 1894, 4,000 Pullman workers did not show up for work. That was only the beginning. More and more workers refused to show up for work, and sympathy for the Pullman workers grew. Accompanying this strike was a boycott, in which members of the American Railway Union refused to run trains that contained Pullman cars. The boycott began on June 26; within days, the total of boycotting Eugene Debs (right), the founder of the ARU, encouraged the strike and the boycott. He called for a peaceful meeting of protesters at Blue Island, Ill., for June 29. The meeting ended peacefully enough, but tempers flared and, eventually, so did buildings, as the crowd derailed a railroad engine and set fire to a few buildings.

The strikers refused to call off their strike, and President Cleveland sent in U.S. Marshals and U.S. Army soldiers to break up the strikes. The Marshals and soldiers eventually stopped the strike, city by city, but not before violence ensued. Dozens of strikers were killed, and dozens more were injured. One estimate was that property damage (not just in Blue Island but elsewhere) exceeded $80 million.

Debs served six months in prison, during which time he read the works of Karl Marx and adopted the cause of socialism. He would eventually run for President five times, at the head of the ticket for the American Socialist Party. Other strike leaders served time in prison after being convicted of civil and criminal charges. Pullman died of a heart attack in 1897. A year later, the Illinois Supreme Court ordered Pullman Town to become part of Chicago. The strike was the first and largest of its kind. It was also the first such union action to be stopped by federal troops. Cleveland, once the strike had ended, ordered a national commission to study the strike and its causes. Cleveland also joined with Congress to create a federal holiday called Labor Day, to honor the nation’s workers. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

One of the very large businesses most affected by this economic downturn was the Pullman Palace Car Company, which was run by industrialist George Pullman (left), who had experience in moving homes to make way for the Erie Canal and for Chicago expansion. The Pullman Company built railroad cars and operated those cars on most American railroads. The company also built streetcars and trolley buses for use in cities.

One of the very large businesses most affected by this economic downturn was the Pullman Palace Car Company, which was run by industrialist George Pullman (left), who had experience in moving homes to make way for the Erie Canal and for Chicago expansion. The Pullman Company built railroad cars and operated those cars on most American railroads. The company also built streetcars and trolley buses for use in cities. Pullman established the company in 1862, amid the nation’s railroad boom. Pullman cars featured upholstered chairs and card tables and quickly gained a name for good customer service.

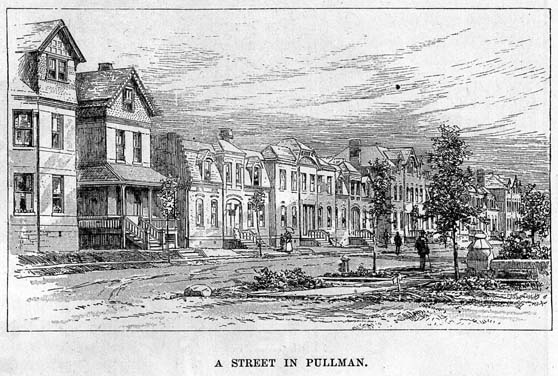

Pullman established the company in 1862, amid the nation’s railroad boom. Pullman cars featured upholstered chairs and card tables and quickly gained a name for good customer service. The Great Railroad Strike of 1877 convinced Pullman that he needed to provide for his employees. He had constructed a large number of buildings on 4,000 acres 14 miles south of Chicago. Pullman named the town after himself, and not only homes with modern conveniences but also shops and hotels and department stores could be found within the boundaries of this “company town.” These were not luxury homes, however, and living conditions for many were not ideal. Some town services, like the library, were not free. Clergy had to pay rent to work in the churches there. Many Pullman employees were required to live in Pullman Town.

The Great Railroad Strike of 1877 convinced Pullman that he needed to provide for his employees. He had constructed a large number of buildings on 4,000 acres 14 miles south of Chicago. Pullman named the town after himself, and not only homes with modern conveniences but also shops and hotels and department stores could be found within the boundaries of this “company town.” These were not luxury homes, however, and living conditions for many were not ideal. Some town services, like the library, were not free. Clergy had to pay rent to work in the churches there. Many Pullman employees were required to live in Pullman Town. The American Railway Union (ARU), which was formed in 1893 by Eugene Debs and to which many of Pullman’s employees belonged, called for a strike in protest of Pullman’s actions. The call was for a strike nationwide. The ARU had led a successful strike against the Great Northern Railway Company in 1893.

The American Railway Union (ARU), which was formed in 1893 by Eugene Debs and to which many of Pullman’s employees belonged, called for a strike in protest of Pullman’s actions. The call was for a strike nationwide. The ARU had led a successful strike against the Great Northern Railway Company in 1893. workers was 125,000, across 29 railroads. Also supporting the striking workers were a large number of men whose job it was to throw the switches at railway junctions. Elsewhere in the country could be found sympathizers who obstructed railroad tracks and otherwise acted to prevent transportation of goods along the railway lines. As a result, in large parts of the country, railway transportation was paralyzed.

workers was 125,000, across 29 railroads. Also supporting the striking workers were a large number of men whose job it was to throw the switches at railway junctions. Elsewhere in the country could be found sympathizers who obstructed railroad tracks and otherwise acted to prevent transportation of goods along the railway lines. As a result, in large parts of the country, railway transportation was paralyzed. The disruption of many of the nation’s rail networks convinced President Cleveland to act. Cleveland directed Attorney General Richard Olney to take action. Olney went into federal court and got an injunction that barred labor leaders from supporting the strike and threatened the striking workers with a mass job loss if they didn’t return to work.

The disruption of many of the nation’s rail networks convinced President Cleveland to act. Cleveland directed Attorney General Richard Olney to take action. Olney went into federal court and got an injunction that barred labor leaders from supporting the strike and threatened the striking workers with a mass job loss if they didn’t return to work. Public opinion on the strikers’ actions was divided, although more people opposed the strike than supported it. Debs was arrested and, because the strike involved stopping federal postal rail cars, charged with conspiracy to obstruct the mail and disobeying a direct order from the U.S. Supreme Court, which had instructed him to call for the dissolution of the strike and the boycott.

Public opinion on the strikers’ actions was divided, although more people opposed the strike than supported it. Debs was arrested and, because the strike involved stopping federal postal rail cars, charged with conspiracy to obstruct the mail and disobeying a direct order from the U.S. Supreme Court, which had instructed him to call for the dissolution of the strike and the boycott.