Pocahontas: the History and the Legend

Pocahontas is the name she is known by the most, but the real name of the Native American girl who John Smith claimed saved him from certain death in early colonial America was Matoaka. How she became known as Pocahontas, savior of John Smith, is perhaps a story of cultural and literary invention.

According to Smith, writing years after the fact, Powhatan had decreed that Smith was to be killed and was in the process of striking Smith when Pocahontas, as he called Matoaka, put her own head on his to prevent her father from killing him. The facts are that Smith put pen to paper in A True Relation of Virginia in 1608 and mentioned the girl; in that work, however, he did not mention that she had saved his life in such a dramatic fashion. That story came in another writing, in 1616. In the first writing, Smith mentioned that he and Powhatan had a discussion about relations between the local tribes and the English settlers. It was only in the later writing that the drama entered the story, when the story was that Smith was captured and saved from certain death by the kindness of the daughter of the chief. In fact, in that 1608 writing, Smith said that he and Powhatan had a long talk after a large feast, with no hint of a dispute between the two men. What is known to be true is that Matoaka did know who John Smith was because she knew who many of the Jamestown settlers were because she, living nearby, made the short journey to the Jamestown settlement several times and enjoyed playing with the children there. She did get on well with Smith and with other adults in the settlement. She is said to have delivered food and medical supplies from her tribe to the settlers on more than one occasion.

As for her name, Matoaka is thought to have had more than one name. Pocahontas is thought by many historians to be a childhood nickname that has somehow been assigned as her primary name. She did adopt an English name, Rebecca, after she had been captured by English settlers, in 1613. A year later, she married tobacco planter John Rolfe. Together, they had a son, Thomas. Although no evidence exists, many writers have crafted a romance between Pocahontas and John Smith. This story of love between the two people has appeared in books and poems as early as 1803 and in movies, in a 1924 silent film and, more recently, a Disney movie in the 1990s. Some historians think that Matoaka was married before (to a member of her tribe) and that she had a daughter from that marriage. John Rolfe would then have been her second husband. She was his second wife; his first wife and their daughter died before he arrived in Virginia.

Matoaka was well-known to English settlers and to other Native Americans during her lifetime. She is much more well-known even today for her nickname, Pocahontas, and for a story that may or may not be true. Matoaka had married John Rolfe in 1614. The next year, Rolfe announced his intention to take his bride, now called Rebecca, to England. In anticipation of this, Smith, who was still living in England, wrote a letter to England’s queen, Anne, telling her how wonderful Rebecca was and that, as Matoaka, she had saved his life. This was the first appearance in writing of that story. Pocahontas was said to have been a princess, since her father was a chief; however, she was at the back of the line of succession, behind several brothers and sisters, and so she was likely not a princess in the way that modern interpretations would have it, as someone who would eventually be a queen or a ruler. As Rebecca Rolfe, she was still the daughter of the powerful Powhatan and was treated as if she were royalty by some in English high society. (To others, she was deemed a curiosity.)

One of those practices was baptism, a holy blessing ceremony involving water. The settlers of the time were quite happy to report that Rebecca, as she was afterward called, had begun practicing Christianity. One particularly famous illustration of this is the 1840 painting by John Gadsby Chapman titled The Baptism of Pocahontas (left). This painting hangs in the rotunda of the U.S. Capitol building.

One of the most famous visual representations of the “rescue scenario” is the 1865 painting John Smith Saved by Pocahontas (below right), which shows Smith, his hands bound behind his back and his head on a rock, as the target of Powhatan’s angry war club, with Pocahontas imposing herself between the two men, with her arm outstretched to forestall her father’s strike and her face to the heavens, as if to implore divine intervention. Another lithograph done just a few years later, Pocahontas Saving the Life of Captain John Smith (below left), by Victor Nehlig (1870), is more abstract, with the Native Americans facing the viewer and Smith, in supplication with his face on a tree trunk, facing his attacker. This much more stylized approach features anachronistic mountains and tepees (neither of which appeared in the Tidewater Virginia landscape in which the Powhatan tribe lived).

The name Pocahontas survives, in the history books and in the names of places and things in the U.S. and in the U.K. Virginia and West Virginia have a few locations named Matoaka. Recognized more by her nickname than by either of her real names, she remains a familiar figure throughout history. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

The facts are these: Matoaka was one of the children of Powhatan, the most powerful chief of a group of tribal nations in Virginia. The name of this group of tribal nations was the Scenacommacah. Powhatan had several wives, all of whom bore children of the chief. The name of Matoaka’s mother is not known. The exact year of Matoaka’s birth is not known, either. Many historians place her birth year as 1596 or 1598, based on the writings of Jamestown English settler John Smith, who wrote in 1608 that she was 10 and in 1616 that she was 12 or 13. Smith was referring to a time when he met her, when he visited Powhatan and other tribal leaders, in 1607, in the same year that English settlers

The facts are these: Matoaka was one of the children of Powhatan, the most powerful chief of a group of tribal nations in Virginia. The name of this group of tribal nations was the Scenacommacah. Powhatan had several wives, all of whom bore children of the chief. The name of Matoaka’s mother is not known. The exact year of Matoaka’s birth is not known, either. Many historians place her birth year as 1596 or 1598, based on the writings of Jamestown English settler John Smith, who wrote in 1608 that she was 10 and in 1616 that she was 12 or 13. Smith was referring to a time when he met her, when he visited Powhatan and other tribal leaders, in 1607, in the same year that English settlers  In 1609, Smith sustained serious injury and returned to England to convalesce; for some reason, the other Jamestown settlers spread the story that Smith was dead. Jamestown records show that Matoaka did not visit Jamestown much after that. In fact, the relationship between Powhatan’s tribe and the English settlers turned brittle again and Mataoka herself was captured, in 1613. English settlers held her for ransom (which included the return of a number of English settlers captured by Powhatan’s tribe) and then, when they got it, asked for more. Historical accounts differ on the details of what happened next; some accounts say that she was angry at her father and wanted to stay with the English. The fact remains that she never returned to her tribe.

In 1609, Smith sustained serious injury and returned to England to convalesce; for some reason, the other Jamestown settlers spread the story that Smith was dead. Jamestown records show that Matoaka did not visit Jamestown much after that. In fact, the relationship between Powhatan’s tribe and the English settlers turned brittle again and Mataoka herself was captured, in 1613. English settlers held her for ransom (which included the return of a number of English settlers captured by Powhatan’s tribe) and then, when they got it, asked for more. Historical accounts differ on the details of what happened next; some accounts say that she was angry at her father and wanted to stay with the English. The fact remains that she never returned to her tribe. Matoaka died, as Rebecca Rolfe, in 1617, when she was just 21. The cause of death is not known, although some historians think that she died of illness, possibly pneumonia or influenza. She was said to have been buried in Gravesend, not far from London. The exact location of her grave remains unknown. A life-size bronze statue of her stands at St. George's Church, near Gravesend. Some historians think that she was originally buried there. A church on that site burned in 1727.

Matoaka died, as Rebecca Rolfe, in 1617, when she was just 21. The cause of death is not known, although some historians think that she died of illness, possibly pneumonia or influenza. She was said to have been buried in Gravesend, not far from London. The exact location of her grave remains unknown. A life-size bronze statue of her stands at St. George's Church, near Gravesend. Some historians think that she was originally buried there. A church on that site burned in 1727. Another element of the Pocahontas story is a religious one. After she was captured, Matoaka adopted the religious practices of the English settlers, who were Christian.

Another element of the Pocahontas story is a religious one. After she was captured, Matoaka adopted the religious practices of the English settlers, who were Christian.  The only known portrait of Matoaka done in her lifetime was an engraving (right) by Simon van de Passe, in 1616. In this now-famous engraving, she appears in European dress but is still clearly seen as Native American. Around the outside of the portrait are both names by which she was known, Matoaka and Pocahontas, and the name of her father, Powhatan.

The only known portrait of Matoaka done in her lifetime was an engraving (right) by Simon van de Passe, in 1616. In this now-famous engraving, she appears in European dress but is still clearly seen as Native American. Around the outside of the portrait are both names by which she was known, Matoaka and Pocahontas, and the name of her father, Powhatan.

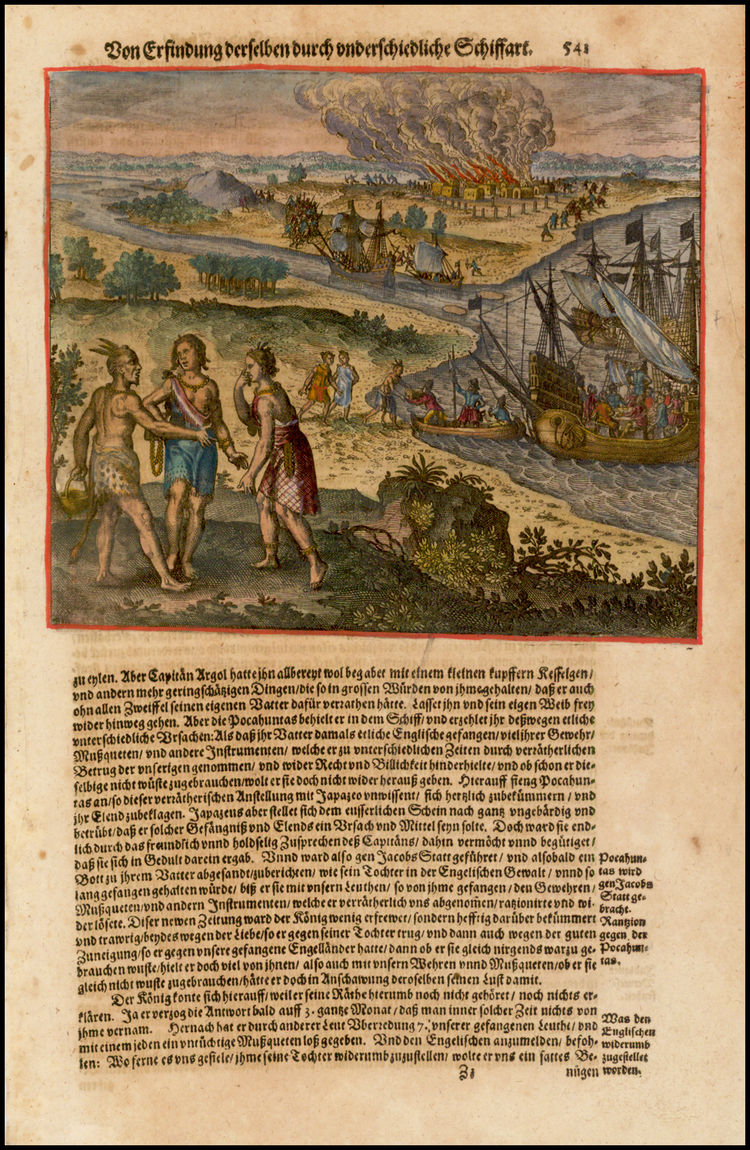

By contrast, artists created few illustrations of a verifiable event, the capture of Matoaka. Known illustrations of this event (along with its related circumstances) date to 1634 (right) at the earliest and 1910 at the latest.

By contrast, artists created few illustrations of a verifiable event, the capture of Matoaka. Known illustrations of this event (along with its related circumstances) date to 1634 (right) at the earliest and 1910 at the latest.