The Peninsula Campaign

The Peninsula Campaign was a battle plan drawn up by the Union Army during the American Civil War. The goal of the campaign was the seizure of Richmond, the capital of the Confederacy, and the defeat of the army defending it.

The architect of the Peninsula Campaign was Gen. George McClellan, who at the time was the Union Army's top general. McClellan had been critical of the Anaconda Plan, the preferred strategy of his predecessor, Winfield Scott, because McClellan thought that plan too timid and too slow to develop. McClellan had formed the Army of the Potomac in August 1861. President Abraham Lincoln had given McClellan the appointment after the solid defeat of Union troops at the First Battle of Bull Run on July 21. When Scott resigned in November of that year, Lincoln named McClellan as his new top commander. McClellan was so skilled at training his men and so adept at equipping them and showering them with praise that they espoused similar feelings for him. At the same time, he developed a strong attachment to the men he trained and equipped and did not want harm to come to them. This hesitancy cost him several times on the field of battle.

A frustrated Lincoln on Jan. 27, 1862, issued Special Orders No. 1, which set a deadline of February 22 for a coordinated land and sea attack on Confederate positions. The goal was for McClellan's army to attack the forces under the command of Gen. Joseph Johnston (right) at Centreville and Manassas. McClellan responded with a rather unwieldy proposition that came to be known as the Peninsula Campaign.

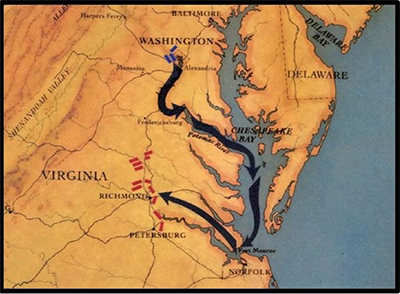

McClellan's plan was for his troops to sail down the Potomac River and then up the Rappahannock River, with the idea to hit Johnston's forces as designated and then, eventually, march on to Richmond. Lincoln was not in favor of this plan because it left Washington, D.C., exposed. Also, as much as Lincoln wanted Richmond captured, he more wanted the Confederate armies engaged and defeated. Johnston, meanwhile, somehow got wind of what McClellan was proposing to do and withdrew his troops from Manassas. McClellan revised his plan to include troop movements down the Chesapeake Bay to Fort Monroe and then on land up the peninsula between the James River and the York River; Lincoln approved the revision. It also came to light about this time that the Confederate troops encamped near Manassas had, when retreating, left behind a number of "Quaker Guns," which were logs painted to look like cannons. This was not the last time that Southern forces used this and other devices in order to convince McClellan and other Union commanders that Southern numbers were larger than they, in fact, were.

Throwing fear into the Union attack plans were reports from early March of a Confederate ironclad warship, the Virginia, attacking Union (wooden) ships. The Navy dispatched the Monitor to deal with the Virginia, which had been harassing the ships of the Union blockade; and the two ironclads met in combat at the Battle of Hampton Roads on March 9, 1862. Neither boat sank the other; for the most part during the four-hour barrage, the bullets bounced right off the iron hulls. At one point, the Virginia tried to ram the Monitor, but the damage was minimal; in fact, the Virginia did more damage to itself. The two ships never met in battle again, although they came close a couple of times. The Confederate Navy eventually scuttled the Virginia after it had sustained too much damage. The Monitor took part in a Union bombardment of Confederate batteries at Drewry's Bluff on May 15, 1862 but did little damage; the Monitor also played a supporting role in defending other Union ships during the Peninsula Campaign, at the Battle of Drewry's Bluff.

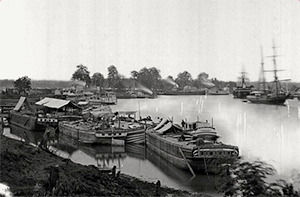

The Army of the Potomac at that time totaled about 130,000 soldiers, 15,000 horses, more than 1,000 wagons, and a few dozen artillery batteries. McClellan successfully transported all of those men all of that materiel to Fort Monroe–rather quickly, in fact. Once the troops were back on land, progress slowed. Confederate troops under John B. Magruder were waiting at Yorktown. McClellan, despite outnumbering Magruder's force 4–1, ordered his men to construct siege works. Johnston moved his force in, to even the numbers a bit, but, with the exception of some heavy fighting at Williamsburg, neither side launched more than a small skirmish for more than a month. Johnston then left again, with McClellan in pursuit. Meanwhile, the U.S. Navy sent an expedition up the James River to reach Richmond; the Confederate defenders were ready for that maneuver and turned back the attack at Drewry's Bluff. The Army of the Potomac crossed the Chickahominy River and was within striking distance of Richmond. McClellan again stopped and waited for reinforcements, despite his force being far the superior in numbers. Johnston's troops attacked on May 31, near the village of Seven Pines (also called Fair Oaks) and were repulsed. Johnston was wounded in the battle, and replacing him at the head of the Army of Northern Virginia was Robert E. Lee.

Again, McClellan delayed, still focused on Richmond but wanting to get his big guns close to the city. Lee called the troops under Stonewall Jackson in the Shenandoah Valley to form a support action and also sent J.E.B. Stuart's cavalry force to circumnavigate the Army of the Potomac, in order to gauge its size and capability. The armies eventually came to blows, in the Seven Days Battles. At Oak Grove, Mechanicsville, Gaines's Mill, Savage's Station, Glendale, and Malvern Hill, the two armies traded blows, neither one gaining the upper hand. McClellan pulled back to Harrison's Landing and was then recalled to Washington, D.C., ending the Peninsula Campaign. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White